If you haven’t seen Black Mirror, well, I’m not sure why you’re here. If you have, you know it is arguably one of the most important and thought provoking shows of our era. TV Obsessive is proud to feature analyses of each and every episode. Here, Caemeron Crain digs into S1E1, “The National Anthem.”

Black Mirror is a show about technology. We are shown, for the most part, near future worlds, where the technologies that already exist have been taken in directions that feel problematic. It is not far out sci-fi; its predictions are less than those made by the original Star Trek, e.g. This isn’t a distant future—it is troublingly near. And the inaugural episode, “The National Anthem” isn’t even quite that. This is something that could happen now. There is no technological aspect that goes beyond the current. Here but the grace of God go we.

This ethos has a way of carrying out throughout Black Mirror. This is part of the show’s interest. It pushes on what already exists to take it in the direction of dystopia. But, this is not just a show about technology. The eponymous black mirror is the screen of one’s phone, or whatever, sure, but it is also about the darkness of our souls. This is a show interested in exploring how we are led to manipulate one another, to take pleasure in each other’s pain, and so on and so forth. It puts up a mirror to the blackness within us.

It is with that in mind that I will claim that “The National Anthem” is actually perfect as the first outing for the series. Again, there is nothing here that goes beyond current technology. If anything, our tech now might be better than when the episode originally aired. But everything is terribly plausible. (Though it would seem that Charlie Brooker was not aware of the rumors about David Cameron and a pig at the time.)

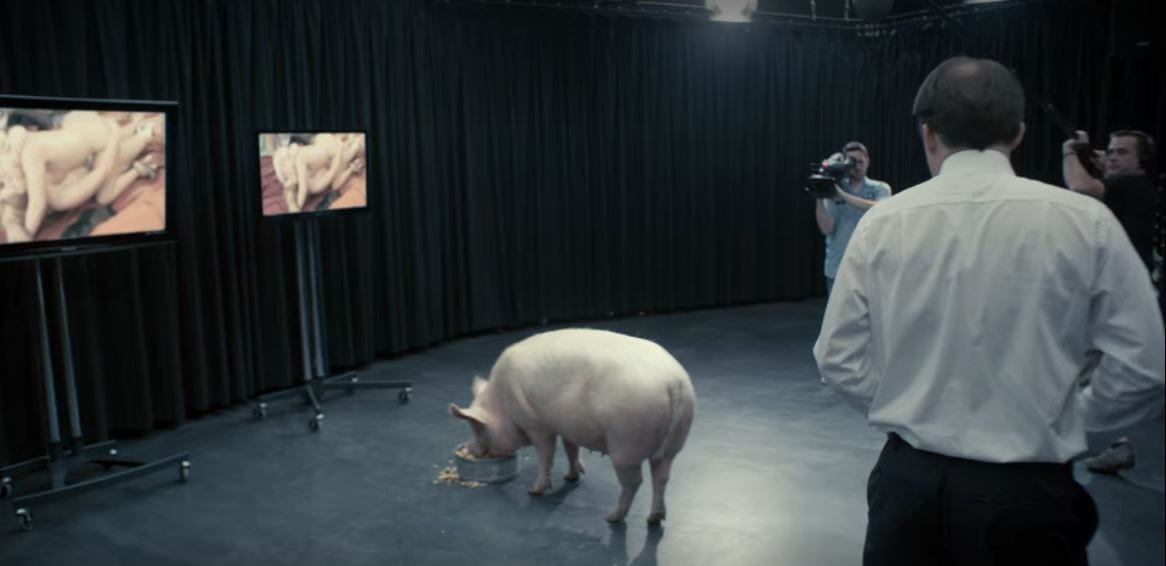

The setup of “The National Anthem” is as follows: Prime Minister Michael Callow is awoken by a phone call, which leads him to a meeting during which he learns that the Princess Susannah has been kidnapped. He is shown, as are we along with him, a video of Susannah pleading for her life, and ultimately reading a statement prepared by her captor. The fundamental demand is that Callow have sex with a pig on live national TV at 4pm, or else the Princess dies.

There is a dark humor to the proceedings of the meeting from the get-go that carries throughout the episode, but I want to focus more on the various questions raised by what happens—these are questions both about technology and ourselves.

Out of the gate, of course, Callow insists that he will not do it, and everyone in the room agrees. Perhaps this is in line with the standard thought of not negotiating with terrorists, but it is worth noting that no one in the room says this explicitly. If anything, the mannerisms of those surrounding Callow suggest that they are already thinking about the affair more in terms of public relations than anything else.

On that note, Callow wants to keep the video itself private, but is informed that it was posted to YouTube, and so on. Thus begins a story arc pertaining to the media in the digital age, and the inability of the government to keep this video, and its demand, from being widely known. At first, broadcasters in the UK go along with the government’s gag order, until they learn that outlets in other parts of the world are running the story. Then, the game is up. The cat (or pig) is out of the bag. There is no longer any discussion as to whether they will run the story, but only about the level of detail they will go into, and the language they will use.

There is, of course, a level of criticism being leveled at the media here, and dark humor, but also a deeper question: 1) While we might generally laud the internet for making information widely available and in-suppressible, are there times when that old school gatekeeping function would be warranted, or to the good? The fact that the demand made is as absurd as it is helps to keep the focus on this issue. This is not a matter of national security, really, though the Princess’s life does seem to be at stake.

But as Mrs. Callow notes, he is already f*cking a pig in everyone’s heads.

And then there is the reporter, Malaika, who uses her sexuality to gain inside information from Downing Street, through the sending of nudes. This presents an inversion to the dilemma that forms the crux of the episode, as she uses technology and sex as a means to coercion, whereas Callow is being coerced through technology to sex.

While the PM focuses on trying to track down the captor and free Susannah to get out of this mess, his advisor, Alex Cairns, works toward a backup plan that involves hiring a performer and using a green screen (or mask) to superimpose the PM’s face. The technical specifications, which involve a roving camera and so on, make this nearly impossible, according to the guy who recently worked on HBO’s “Moon Western”—but they are going to try, anyway. This is one area where current technology may have to some degree outstripped that of when this episode was made a few years ago. But, I am no expert in this area, and the certainly the time constraint involved would be a relevant factor.

Regardless, it does not work, as the kidnapper learns of the attempted deceit—again through social media, as a passerby recognizes the performer, Rod Senseless—and sends a finger (purported to be that of the beloved Susannah) to the media. What is interesting is how this sways public opinion. Initially, polling showed that a large majority agreed that the PM should not f*ck a pig on TV, and said they would of course not watch such a thing. This shifts after the finger, which raises the question as to why: 2) Is it the finger, or the thought that they were trying to cheat? In other words, why does this event turn things on its head?

This shift is both irrational, and yet makes sense. It is irrational because nothing has fundamentally changed, and because the idea of bringing in a willing “stunt cock” to trick the captor seems like a rational path to explore. I mean, of course the government would do that. But that is part of why the shift in public opinion makes sense. The idea that no one should f*ck a pig has been undermined, if they are willing to hire some other guy to do it. All of those cynical anti-government sentiments kick in. And, then, there is the finger, which makes concrete the threat to Susannah, as did the toe in The Big Lebowski. The public isn’t going to react like Walter, but rather like the Dude: “They took her f*cking finger”. It’s serious. The threat is real, and that leads the public itself to face what may be the deepest ethical question posed by “The National Anthem”:

3) Should one have sex with a pig if that is the only way to save the life of another? The question is absurd on its face, but only because of how outlandish the scenario seems. This isn’t something that will come up, or should come up, but here we are. And though Black Mirror is fiction, to be sure, we have to ask ourselves how far-fetched this whole thing actually seems.

The immorality of bestiality is, in itself, a somewhat tricky thing. I take it we all tend to agree that it is wrong, but it is less than clear what the reasons are for this. It’s icky, sure. One might worry about the animal’s inability to consent (though pigs surely do not consent to be killed for bacon, either), or point to a potential trauma on the part of the animal (though this is less than clear as well). The visceral reaction, however, is strong, and that fact that the pig is eating when Callow enters the room only serves to further bring this disgust home.

The pig is the quintessential example of the filthy animal contrasted with the higher parts of human nature. As John Stuart Mill writes in his essay on Utilitarianism, “It is better to be a dissatisfied human being than a satisfied pig”—because critics of the view were claiming precisely that it demeaned humanity to the level of such. Perhaps it is a concern with the degradation of the human involved that lies at the heart of our moral disgust; a reduction to the brutely animal aspect of the self.

Now we are asked to compare this visceral disgust to the value of a human life, or the question of what one should be willing to do to save a life.

If we take a consequentialist point view, such as that of Utilitarianism, it seems clear that Callow should do it. If we compare the pain/suffering he will endure from the action with the value of human life, it would appear to be almost a no-brainer.

It would seem that moral theories in general struggle with this. Take Kant’s moral theory as a counterpoint. It views morality as being not about consequences, but based on rationally determining one’s will. Could this be a universal law of human behavior? Does it amount to treating a person as a means only? It’s not clear that we get a strong moral dictum from this approach, either, particular given the way that Kant denied that animals have a moral status to begin with. If it is our rational nature that makes us matter morally, and the pig lacks that, it would not seem to matter what one does to a pig, in itself. The best Kant could do would be to argue that the act of bestiality does harm to the character of the person doing it, but even there it is hard to point to precise reasons as to why.

Many might say bestiality is wrong because it is “unnatural”. I would suggest that this is but to give a different label to what I have referred to as visceral moral disgust. We tend to all agree that it is wrong, but our judgments would seem to be based far more on emotion than on reason. Of course it is wrong to coerce Callow into this situation, but that is not the point. Once the situation holds, the question becomes a matter of comparing our moral disgust at bestiality with the value of a human life. Or, at least, a matter of thinking about whether we are willing to hold that refusing to be coerced is an absolute value, or one with consequentially determined limits.

It is also worth noting how thoroughly the decision making process on the part of those politically involved is pinned to public sentiment, as opposed to being a matter of principle. One could well imagine the argument that Callow should not do this because it would demean the office, or because we should never negotiate with terrorists, or what have you. This does not occur. But rather than seeming like an oversight on the part of the show, this seems to be all too realistic. As does the claim that they can’t guarantee the safety of his family if he refuses, given the trend towards doxxing and the like. This continues right up to the event itself, as Cairns informs him that the advice they are getting from psychologists is that going too fast might be misinterpreted as eagerness. This is about the psychology of the audience, and not Callow himself, who ends up distraught and puking on the bathroom floor.

It all makes sense, whether it is rational or not, and despite the polling we were previously shown, it seems as though just about everyone is tuned in to see the event when it happens. The streets are empty. What does this say about our human nature, and the difference between what we are willing to report and what we do?

It is not clear whether his wife watched, as scenes of her on the bed are intercut with scenes of those watching. But, it does not matter. His marriage is effectively ruined by this in a way that is relatable—no matter how understandable his actions, it would seem to be something she cannot get past. And that makes sense, even if it is also irrational.

The biggest question the episode poses, though, is, I think, about the intentions of the hostage taker and maker of the demand, Carlton Bloom. We see him now and again, throughout, though we may not know it. At the end, we learn that it was his finger that he cut off. And that he let Susannah go half an hour prior to the pig f*cking. And that he hanged himself during the same. How do we take all of this?

In the scenes interspersed with the closing credits, we get the claim that this was the first great artwork of the 21st century. Does that hold up? Is this performance art that implicates the powerful? If it is a statement, as Alex Cairns says after she learns of when he let Susannah go, what is the statement? Mark this as (4): What is art, and what are its limits?

4a), then, is why did he hang himself? I see two fundamental options here. Either, it was to complete the artwork, or to avoid being asked to interpret it, if you like, or it was because the whole thing was actually a test. If we take the former option, we might further think about how the finger could be used to identify him and so on and so forth. But I find myself leaning towards the latter option. Carlton Bloom was interested in seeing how the PM, the government, the public, etc. would respond, in the hope that there was still decency and decorum in the world. He hoped the PM wouldn’t do it. He released her prior, after all. He hoped the public would be disgusted and stand behind the PM in his refusal. He hoped, in short, that we were better than all of this. And we weren’t. So, he killed himself.

I don’t know if that’s right, and you are certainly free to go the other way, but I want to end with some reflections on the title of the episode: “The National Anthem.” On the one hand, this is almost a bit too on the nose—“God save the Queen”/Princess—but on the other, it hits at something more thematic: the spirit of the people, whether in the UK or US or anywhere else, and their fickleness, tendency toward schadenfreude, and general baseness. Of course we’ll all tune in to watch the leader f*ck a pig on live TV, even though we’ll say we won’t. Who wouldn’t!? And who wouldn’t hit record at the very moment when the voice on the TV tells you possessing a copy tomorrow will be a crime? (OK, I get that some wouldn’t, but that’s not the point).

The point is that “The National Anthem” gets at our celebration, fascination with, and enjoyment of the grotesque and perverse. (What could unite us more, as a nation, than our leader f*cking a pig on TV?) It plays with the accessibility of anything and everything and takes it toward the limit. It asks us to think about what our positions would be in this absurd, but unfortunately plausible situation. It makes us look into a black mirror.

It could be as simple as explanation as the artist is reflecting the horrible things people do to each other, the horrible things people want to see done to each other and the horrible steps governments will take in both cases. I think Michael said it best with “Man in the Mirror.” We are all pigs at one time…

Ok, but why does he hang himself? I found myself getting really caught up on that. Part of the art?

Would you rather hang yourself as an artist and be a part of your art? It used to be that you would be remembered for decades, now it is whittled down to years…Or would you rather rot in jail and be completely forgotten after the next “BIG” thing? It takes a lot to kill yourself when you are of sound mind (Natural Survival instincts and all that) but it seems to be easy for the mentally affected….

maybe he did it because the world is as sick as he feared

It could be as simple as explanation as the artist is reflecting the horrible things people do to each other, the horrible things people want to see done to each other and the horrible steps governments will take in both cases. I think Michael said it best with “Man in the Mirror.” We are all pigs at one time…

THANK YOU!!!

I was going to review “ten” sources to get to the philosophical, historical, psychological mountain that the episode, quite brilliantly (within its scope) achieves, but NO!—-your excellent review of it, including the Kant extrapolation that I, poor sucker can barely understand (because I gave up on “Critique of Pure Reason” after (well, damnit, I have nothing to lose anymore!) the two prefaces!) provide us all with the necessary tools to wing it when in “serious” conversation posing as an intellectual….Which goes back to some of the points you make—-in other words, most of us are charlatans…Hahaha…

You write so well!

Cheers!

Thanks! I know some people don’t care for it, but I think it is a really interesting episode