The core of Netflix’s 2017 drama series Dark is time travel. Talked about, meditated over, and weighed as fantastical or terrible by the different characters in the series, it provides not just the impetus for the plot of the show, but the philosophical conundrums the characters consider and exist within.

The problem is time travel, according to our current understandings of the physical sciences, is actually impossible. Not just because there’s no known way of actually creating a time machine, but more importantly, because time travel would have major implications on the causal understanding of the universe, which underpins the scientific method itself. Yet Dark manages to weave a time travel story that maintains a level of plausibility, while turning the inherent paradoxes, contradictions, and overall moral messiness of time travel into the thematic and character threads of the story itself.

What Dark isn’t, is overly concerned with the scientific solution to time travel. Aside from a few references to an Einstein-Rosen bridge – a type of black hole that theoretically connects two points in spacetime – time travel seems to just happen. There’s some ambiguity about whether a machine Jonas – the main character in the series – uses actually creates part of the bridge, embiggens an already existing bridge, or does nothing at all. While there may be more detail waiting in the wings of future seasons, in season one, Dark is happy to treat time travel as a magical plot device.

What it is very much concerned about is the impact of time travel and all the issues that come along with it. And boy are there plenty of issues. Perhaps the best way to illustrate the logistical and philosophical problems associated with time travel is with one of the most-often cited questions about going backwards in time: the grandfather paradox.

If someone were to go back in time and kill their grandfather before their mother or father had been born, then that means the time traveler would never have been born. Which means the time traveler could not have gone back in time to kill their grandfather. But if they didn’t go back in time to kill their grandfather then their grandfather would live and the cycle would start all over again. A classic paradox.

One of the most memorable (from a pop culture standpoint anyway) instances of the grandfather paradox was in Back to the Future, when Marty McFly goes back to 1955 and stops his mother and father from falling in love. In that film, Marty begins to fade out of existence (during his performance of “Earth Angel”), as the connection between his mother and father disappear, but it’s not at all clear how that would impact the future, specifically whether Marty not existing in 1985 would mean he wouldn’t go back in time to 1955 and screw up the timeline in the first place.

Most time travel stories, especially when told in Hollywood features like Back to the Future, try to avoid dealing with the implications of the grandfather paradox. Part of that is because according to the linear way we all look at the world, it really doesn’t have a solution. You simply can’t go back in time, kill your grandfather, and not cease to exist yourself. It’s a paradox with no logical solution.

Except one. The grandfather paradox isn’t a paradox at all if the man you killed was not your grandfather.

Say you, like most people, only knew your grandfather as an older man. One day you saw a photo of him as young man and you remember it clearly. So when you get sent back in time to kill him (for whatever reason), you remember that image of him as a young man and you go on the hunt. You find him, and you’re sure it’s the right man. Because he can’t possibly identify you, you approach him and talk to him. You confirm his name is the same as your grandfather’s name. You take a blood sample and somehow perform a DNA test. It is absolutely 100% your grandfather. Completely certain, you kill him. Yet you still exist. You stick around in your version of 1955 and wait to see what went wrong.

It’s only at the man’s funeral that you realize your actual grandfather had a twin brother who had been horribly murdered as a young man – a story your family was always too hurt to share with impressionable young members of the family like yourself. So grieved by his brother’s death, your actual grandfather took his brother’s name and lived the rest of his days under that identity. You’ve actually not killed your grandfather at all, you’ve killed your great-uncle.

Determined to kill your grandfather, you make another attempt at the funeral, only the police – there to comfort the grieving family and suspicious the murderer may be in attendance – pounce and arrest you before you can do the deed. You’re sentenced to life in prison, despite your name not appearing in any birth records (because you haven’t been born yet), and you spend the rest of your days behind bars. Meanwhile your grandfather grows old, has children, and then grandchildren; including a younger version of you, who will one day grow up, go back in time, and fail to kill his grandfather.

Put simply, the grandfather paradox can be avoided if all the actions you, as a time traveler, will take in your future, have already happened in the world’s past. In this case, time isn’t so much a straight line, as a series of loops, where time travelers swoop backward in time (or forward, though it’s slightly more confusing in those cases), and do something that has already happened. Not only is time travel possible, but it’s actually necessary to avoid a paradox. If you hadn’t gone back in time to try and murder your grandfather, he would never have taken the name you knew him by as a child, the name that helped you mis-identify his brother as your target.

What makes Dark so interesting is that it not only created a tightly cohesive first season where there are no grandfather paradoxes, despite continual time travel, but it showed just how the grandfather paradox would be avoided through the motivations and drives of the characters, even those who are aware of time travel and seek to use it to their own ends.

Set in three time periods – 1953, 1986, and 2019 – with some characters appearing in all three, the time travel in Dark pushes and pulls different characters across the multiple time periods and shows how just a tiny bit of knowledge about the future can drive people to do terrible things in the past.

There are two major scenes from the series worth examining, where characters from the 2019 timeframe go back in time to try and change the past, which show how the grandfather paradox is so integral to not just the plot arc of Dark but the stories of the individual characters.

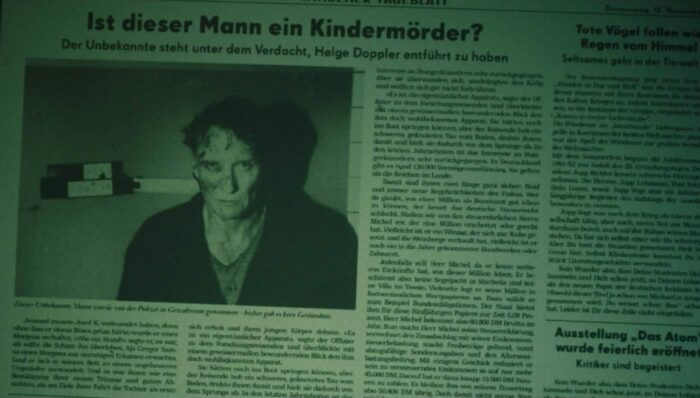

The first, in a strictly chronological sense, occurs in 1953, when Ulrich Nielsen, freshly transported from 2019, viciously tries to murder Helge Doppler by crushing the young boy’s head in with a stone. Viewers may have noticed that versions of Helge that appear in 1986 and 2019 have scars on the side of his head from the attack. Presumably even Ulrich may have noticed that, and wondered why the young version of this man didn’t have these scars, but he’s too enraptured in the moment to think clearly.

Ulrich wants to kill this child version of Helge because he knows Helge has some sort of connection to his own son’s disappearance in 2019. Perhaps driven by his own grief at losing his son, and/or disoriented by the time travel, Ulrich acts rashly but with clear motivations. Though it’s not his grandfather, Ulrich has arrived in the past with an opportunity to kill someone – Helge – he believes will do great harm in the future. Ulrich believes he can change the past. In reality all he does is complete the loop that had started years before he was even born. Helge’s scars are the lasting mark of Ulrich’s desire to do good, but they actually help push Helge towards supporting the shadowy Noah character, and to become a suspect of Ulrich’s in the first place. Ulrich arrived back in time with a chance to stop Helge from becoming a suspect, but he actually creates the conditions that lead to Helge into becoming a suspect. A somewhat convoluted but distinct loop in time.

The example of Ulrich is very similar to the hypothetical grand-uncle killer: they both mistakenly believe in their ability to create a paradox, unintentionally fulfilling the linear order of cause and effect that led to their birth, movement through time, and attempt at changing the past. But what if your goal wasn’t to change the past at all, but to ensure it didn’t change?

That’s the case in the second major time-traveler incident involving not one, but two Jonas Kahnwalds. Jonas, a young man in 2019, also appears as an older, grizzled, dystopian-survivor figure in 1953, 1986, and 2019. While the two Jonas’ meet several times, one of their first encounters is the most telling.

At this point, teenage-Jonas has gone back to 1986 to find the brother of his would-be girlfriend, a pre-teen boy named Mikkel. Mikkel has been sent back in time against his will, and Jonas has just learned that Mikkel will, if left alone, grow up in 1986 and actually become Michael Kahnwald, Jonas’ father. The stage is set for a classic Marty McFly-esque paradox: if Jonas is successful in taking Mikkel back, he won’t become Michael and won’t create Jonas in the first place. Undeterred by this potential conflict, Jonas is about to go talk to Mikkel and take him back to 2019 when the older, post-apocalyptic-looking Jonas appears and convinces him not to do it.

This scene is actually an amazing example of a loop in time that avoids a grandfather paradox. Not only because it literally involves Jonas’ father, but because Jonas is solely responsible for the loop forming and closing. Teenage-Jonas is thinking just like Ulrich, that he can change the past for the better. But older-Jonas has come to the realization that above all else, the timeline must be preserved – a piece of knowledge he shares with the younger version of himself. Somewhere in Jonas’ life between those two moments, he’s come to this realization on his own, and come to believe it so strongly that he stops his younger self from creating a paradox, which is likely a key moment in his own life in coming to that realization. This particular loop is so tightly wound that the slightest miswording on older-Jonas’ part could jeopardize everything – if, say, he failed to convince his younger self not to interfere, the paradox could potentially destroy the universe (if Doctor Emmet Brown’s analysis in Back to the Future is anything to go by).

But of course, that’s not really a possibility. As aptly described in this meme:

(What do we want? Time Travel! When do we want it? That’s irrelevant!)

Put simply, if time travel were to cause a paradox, it would have, in a sense, already happened. It would have always happened.

Because Dark is so dedicated to telling a logically plausible time travel story, full of loops that, in the show’s parlance, reach into the past and the future at the same time, it’s worth noting that it inevitably latches on to a certain metaphysics to help tell its story: hard determinism.

For those who didn’t invest four months of college in a Philosophy 101 seminar, hard determinism is a way of looking at the world where all events are directly caused by those that came before them. In effect, everything is predetermined, and human choice is a fantasy. All our choices are actually just made by atoms and chemicals in our brains that follow certain unbending rules of physics. We’re all just gears in a giant clock, ticking away, being driven by the causes that drive us and having effects on the things that follow us, without any actual agency in any of it. We may perceive to have a choice, but actually our choices will always be what they will be, no matter how much we feel or think we have control over them. In this sense, there’s never any chance that time travel will cause a universe-destroying paradox, because if it were going to happen, it would have already happened. Jonas was never at risk of not convincing himself to leave Mikkel alone, because the loop of time was always going to be closed as soon as Jonas opened it by going backwards in time in the first place.

What makes Dark really compelling to watch is the fact that all these time travel considerations are mostly just floating in the background. The story is always anchored by understandable human emotions that have relatively little to do with time travel. Fathers missing sons. Sons missing fathers. Long-simmering jealousies and desires. In many ways, time travel in the series is just a chance for the viewer to see the people in this small town grow up, follow in their parents’ footsteps, and never deal with the issues that haunted them as teenagers. Only three characters from 2019 – Ulrich, Jonas, and Helge himself, as an old man – actually time travel, yet the impacts of that travel reverberate forward and backward on the lives of all the other characters, in ways that feel completely normal and everyday. For a series that took great pains to get time travel right, it’s really not the central conceit the way it is in Back to the Future.

It’s only near the close of the first season that we start to get the sense that there are competing interests trying to use time travel for their own purposes: the previously mentioned priest named Noah on one side, and Claudia Tiedemann, a onetime manager of the town’s nuclear power plant, on the other. Both seem to be fighting some sort of proxy war through time, appearing and disappearing in the different time frames. But ultimately the metaphysics of the show would lead you to believe that neither of them are ultimately “successful” in any way, because their actions have always happened and will always lead to the same result: which, if they’ve travelled into the future, they already know. It’s not clear then, what their motivations are, or where Jonas, in particular, fits into this possible battle between good and evil. It’s not even clear which side is actually which when so many loops of time are opening and closing on screen at any point in time.

And in the middle of all these loops remain central characters who are dealing with rather mundane issues, and being forced to make choices that, whether they know it or not, are predetermined. What’s great about the series is that the choices never feel predetermined to the viewer – the characters act in ways that make sense and are consistent with what they believe and have experienced. Their choices still feel like choices the way they would in any other TV series, despite the show’s deep commitment to actively removing the element of choice from the overall timeline. The viewers are simply along for the rides as each of the would-be grandfather killers goes on their adventures through time travel.

While we will have to wait to see what future seasons of the series have in store, it will be quite a treat to watch and see if the creators can keep the many tightly wound time loops from getting in the way of one another. As more time periods open up to the characters, and the battle between Claudia and Noah becomes clearer, the logical hoops the show will have to jump through will just build and build. If it pulls it off in a way that’s as watchable as the first season, Dark will be a series worth watching over and over again.

Let Aidan know what you think! You can follow him on Twitter (@aidanhailes)