The final two seasons of The West Wing split the cast up between those off running in the 2006 Presidential Election and those who stayed behind to staff the Bartlet White House in the final year of his second term. The first four seasons of the show were fairly episodic, in the best sense of the word. Serious events would occur, and the collective brilliance of the President and his senior staff would save the world, averting everything from PR gaffes to government shutdowns to constitutional crises. In later seasons, as the idea of Prestige TV began to take hold, The West Wing responded to the growing tendency toward long-range stories and planned vast character and story arcs that led them right through to the end.

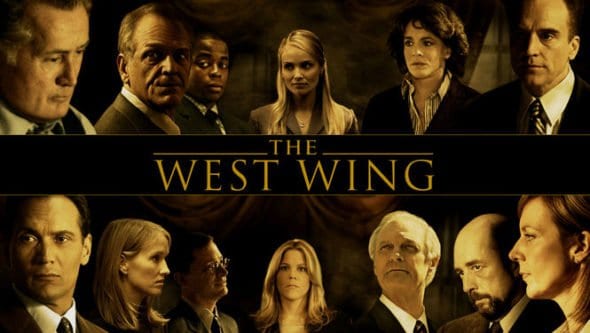

But the strength of this series was ever and always in the massively talented ensemble cast, and seeing them go their separate ways starting early in Season 6 was a tough pill to swallow. There were a lot of questionable decisions made that fans of the show debate about to this day. The most prominent of these was Toby Ziegler’s (Richard Schiff) inexplicable fall from grace—he leaks information to a New York Times reporter about the existence of a secret military shuttle that could have saved the lives of crew members trapped on the ISS, triggering a full investigation and leading directly to his termination, the jailing of the Times reporter, and his own criminal trial—which is one of those most hotly contested; personally, I’ve always seen the beginning of Toby’s decline in the moment Josh Lyman (Bradley Whitford) leaves the White House to become campaign manager to Matt Santos, tracing a line back to the fact that everything was better when everyone was together.

There were also real-world events that intervened, for better and for worse, and tested the strength of the show’s writing. Leo McGarry’s (John Spencer) heart attack at the start of Season 6 led to a lot of shakeups, as CJ moved from Press Secretary to Chief of Staff, but as Season 7 wrapped up and John Spencer himself suffered a fatal heart attack, his character’s death had to be written into the show as well. It changed the trajectory of the election campaign that McGarry had been thrust into as Matt Santos’ Vice Presidential running mate—the story goes that the original plan was for the Republican candidate Arnold Vinick (Alan Alda) to win the election, but that the choice to have Santos win instead was purely decided by the dramatic death of one of the show’s regular cast members and his on screen character. But it also hammered that nail in, once again, that things were never going to be the same. In subsequent rewatches, I know many people who feel that Leo’s heart attack, his recovery, and his untimely death the following year storyline cast shadow over the entire final two seasons, an unintentional premonition forecast at an eventful but heartbreaking (literally) Camp David summit between the Israelis and Palestinians.

While these final two seasons were far and away better than the much-maligned fifth season (immediately after showrunner Aaron Sorkin left, taking the show’s spark along with it), it still felt, at times, to be a very different show than the one we all started watching in the autumn of 1999, for reasons both created and unavoidable.

But in spite of losing the heart of the show in more ways that one, the final seasons of The West Wing brought things back into focus, even as its lens followed characters all over the place. And in contrast to the series finale, you can look back at the show it was seven years earlier and not completely recognise it but like most changing Presidential administrations there are glimmers here and there that show us that what we have now is not so different from what we had then.

“Tomorrow” is set on Inauguration Day, January 20th 2007. In the aftermath of Matt Santos’ (Jimmy Smits) not-so-surprising win over Arnold Vinick (Alan Alda) and in the shadow of Leo McGarry’s untimely passing on Election Night, the transition of Jed Bartlet’s presidency to Santos’ is in full swing. As the West Wing staff clean out their desks and prepare for the imminent arrival of the Santos staff, we get to see the two sides of every Inauguration: the sadness and nostalgia of the departing team and the excitement of those incoming. It helps that so many of the incoming team are old Bartlet staffers, now along for the ride with the energetic young Congressman from Texas whose political movement swept him right into the Oval Office. There’s some nice “getting the band back together” sentiments, especially when we first see the crew—led by Josh and Donna (Janel Moloney) and Sam (Rob Lowe)—walk into the West Wing lobby with excited trepidation in their eyes.

Along with this hustle and bustle, some big questions loom; chief among them is whether or not, as his last act as President, Jed will pardon Toby Ziegler for his treasonous acts earlier in the season. This is something that Jed grapples with throughout this final hour.

It’s not a particularly momentous episode, and some might argue that this makes the finale fall flat. But I disagree. Not every day in the West Wing needs to be filled with scandals and international incidents, and Inaugurations typically run smoothly—crowd-size debates notwithstanding. So it seems rather apropos that the final episode should be one of small gestures: Jed leaving the Residence for the last time and being gently chastised for his lateness by wife Abby (Stockard Channing, in the role she was born to play); her worry about his “re-entry problems”, as this is the last job he’ll ever hold and after a lifetime to politicking, that’s gotta be a tough pill to swallow; the tenderness and playful humour between Matt and Helen (Teri Polo) as they begin their life as the First Couple with nine—count ‘em!—nine inaugural balls to attend after the swearing in; the fresh nervousness of Josh and Donna as they enter the West Wing now as Chiefs of Staff respectively to President and First Lady.

Of course nothing beats the final unwrapping of Mallory’s gift to Jed aboard Air Force One as he leaves Washington for his New Hampshire farm: the framed “Bartlet for America” cocktail napkin that her father Leo gave to Jed, the object that started them all down the path towards 8 successful years in the White House. It brings a chill to my spine and a tear to my eye even thinking about it.

As tempting as it is to imagine a compassionate Republican helming the White House—especially in these turbulent and often rudderless times—there is a certain poignancy to the idea of a Santos administration. That Santos’ rise within the show so closely parallels that of Barack Obama’s in real life only adds to the hindsight allure of the final season. This spirit of bipartisanship is present throughout, most beautifully in the moment when Santos asks Vinick to be his Secretary of State—another parallel to Obama, who asked Hillary Clinton to run his State Department after beating her in the 2008 Democratic Primary. So there is something oddly nostalgic about this, as well.

In fact, the entire finale might be tinged by this nostalgia for a better, more cooperative time. If you’ll allow me to get personal for a moment: my husband Aidan and I have rewatched The West Wing annually for about ten years now, starting in early fall and taking us through the long cold northern Canada winter months. The 2016 U.S. Presidential election left us so weary of the political process and the animosity that accompanied it put us off watching The West Wing entirely—this year may be the first time we’ll watch it since, and even that isn’t for sure. How can we watch the promise of peaceful cooperation between Republicans and Democrats when the current climate is so anathemic to that process in real life? It’s an almost certain set up for disillusionment and disappointment.

But I’d argue that the idealism of the entire series and certainly that of the finale are exactly the kind of thing we should watch for and strive toward. Aaron Sorkin didn’t create something that was meant to be true to life; his left-wing political leanings, here and also in his short-lived HBO series The Newsroom, earned him the vitriol of viewers on both sides of the aisle who could at least agree that he was too heavy-handed in his views. And yet it’s true that fiction doesn’t need to mimic real life. It can be aspirational, a vision of something that could be rather than a perfect simulacra of what actually is. In this way, The West Wing as a series and the finale as a part of that could (and arguably should) be held up as something to work towards.

The United States of America may not be a place where the spirit of bipartisanship can exist easily now; some question if it ever will again. But for a brief moment in time, in a writers’ room somewhere in the NBC offices and then on the California soundstages that stood in for that greatest of metonymic symbols, a team of talented writers and producers and actors and directors showed us what was possible when good people who want to do good things work hard and fail as often as they succeed, before stepping back and reassessing and starting all over again.

And if you don’t think that’s a beautiful thing—to paraphrase the late, great Mrs. Landingham—then God, readers, I don’t even wanna know you.

Well said. I’m currently watching the West Wing Marathon on HLN and am reminded of what “must see TV” was all about. As soon as the theme song begins I get ready for compelling story-telling.