Hidetaka Miyazaki, Bloodborne’s game director, has said that how he got his entertainment as a child shaped his core game design philosophies. He read stories and watched shows in English, a language he did not speak, and only half understood what was happening. The rest he filled in with his own imagination. Miyazaki saw the outline of the puzzle, and where he saw holes, he shaped new pieces to create his own story.

Most story-driven media are, by their nature, designed with the narrative in mind. Characters go here, do this, and see this as a result. Their tales are clear, with the results of their actions being the focal point. It’s rare to find a medium that does not care if you understand what is going on, one that seems to be intentionally obfuscating the story behind silent characters and hidden lore. Yet Dark Souls and Bloodborne revel in this style of story-telling. Your goals are rarely clear, character motivations are muddy at best, and the results of your actions are never obvious.

In almost every recent From Software game (Sekiro not included), your character awakes or is rescued by a mysterious individual and subsequently told to go out and do… something. What you are told to do is not only different from game to game, but also explained in the vaguest terms possible. The first Dark Souls tells you to escape the Undead Asylum, but you can finish that in under an hour. So what then?

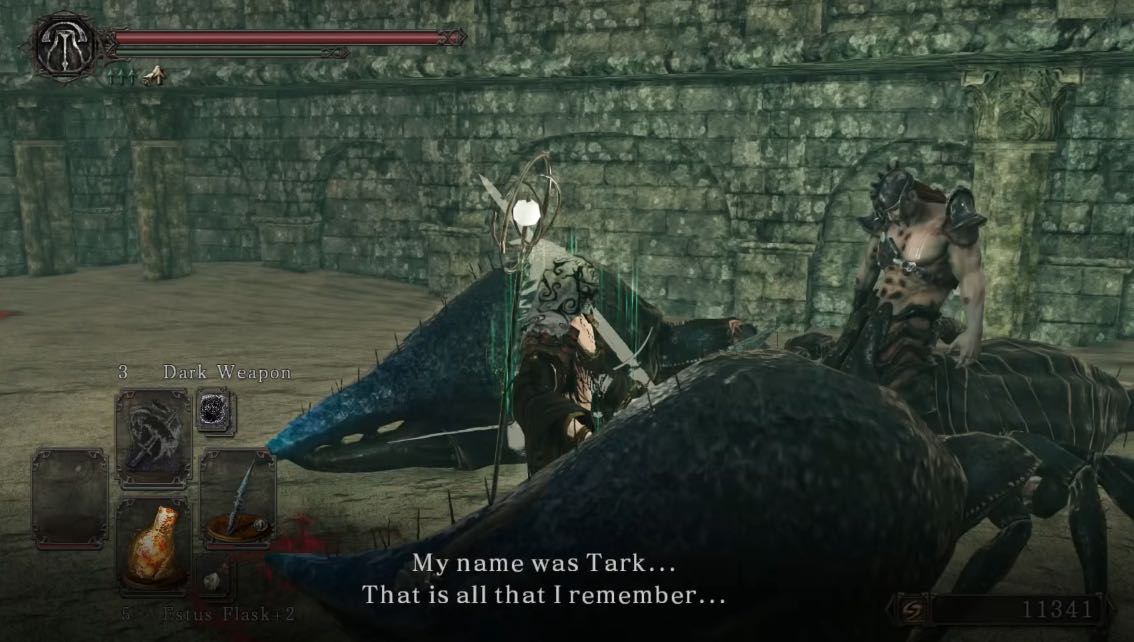

Slowly, Dark Souls’ story begins to unfold as you play. Characters hint at some ultimate quest. Ring the bells, kill the Lords of Cinder, and so on. But even in these moments of clarity, conflict and lore remain hidden from plain sight. The Lords may be more than they seem, hiding tragic backstories and reasons for their existence. The bells may awaken more than a new era. And almost every bit of this lore is completely missable.

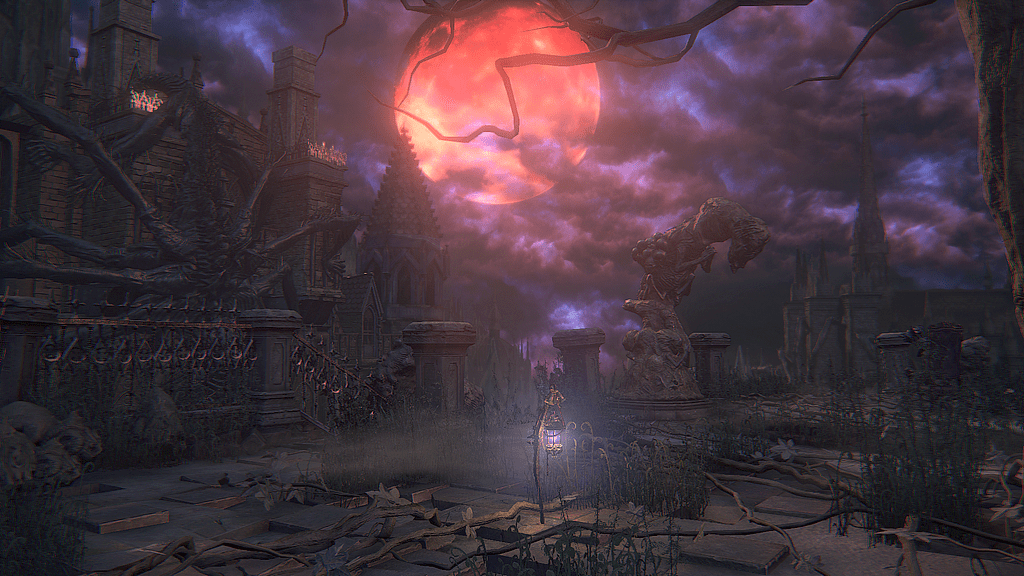

Bloodborne takes ambiguous storytelling a step further. You awaken and, presumably, are immediately killed by the first enemy you encounter. You awaken again in a strange land filled with creatures offering weapons and tutorials, but no lore. A doll sits ominously in the corner. You return to Yharnam, armed and ready to fight. But to fight what? What threats actually await you? The opening hours offer no real answers, just a journey through a city wracked with chaos and monsters, thirsty for literal blood.

I finished my first play-through of Bloodborne feeling more than a little lost. Certainly, I understood chunks of the game, bits of what was happening. I pieced together the growing Eldritch threat that resided within the city, but I assumed it to be a conflation of two dimensions, intersecting on the night of the Blood Moon. I gained Insight and Knowledge, recognizing that it pushed me further in the story, but the breadth of their effects was lost on me. Each success, each bit of progression rewarded me with enough encouragement to continue on, no matter how lost I felt.

The Incomplete Puzzle

This is where Miyazaki’s design philosophy really comes into play. I went from area to area, slaughtering and being slaughtered just to find the next bit of lore, of story to push myself forward. I stumbled into the Hidden Village of Yahar’Gul and made assumptions on how I ended up there. There was a dissonance between my understanding and what I was seeing. I assumed the game world to be singular, one without areas disconnected from the rest of the world. So, I made my own connections. I created puzzle pieces shaped in a way to connect Yharnam and Yahar’Gul. It didn’t matter whether the two cities actually connected in that way.

You can find all of the “true” puzzle pieces in-game. The caveat is that the developers went to great lengths to bury them. While the SoulsBorne series may be light on story-telling, they are dense in lore. Almost every weapon, every item has a story to tell if you care to look for it. Some tell small tales of triumphs and terrors. Others fill in the gaps between Yharnam and Yahar’Gul. A few just explain what a dung pie is (spoiler warning: it’s poop). But even these stories have a caveat: You need to find them.

Provided you realize that items have lore tabs, provided you have diligently read each one, it’s still remarkably likely you’ll be left with an incomplete picture. The game hides these items, these bits of lore everywhere. To learn of a dragon, you may need to find a way to cut off its tail. To understand deep magic, you may need to search behind illusory walls. The SoulsBorne series know its lore is nigh inscrutable, almost impossible to piece together in a single play-through. They want you to write your own story.

The SoulsBorne series is incredibly unique in the modern era of games. It’s a series of deep lore and shallow storytelling. Every bit of information you may uncover feels like a triumph, another piece of a puzzle to help create the full picture. And while every game builds on the events of the story to create that picture, only the SoulsBorne games allows that end result to vary wildly from player to player.

The History of Building Personal Narrative

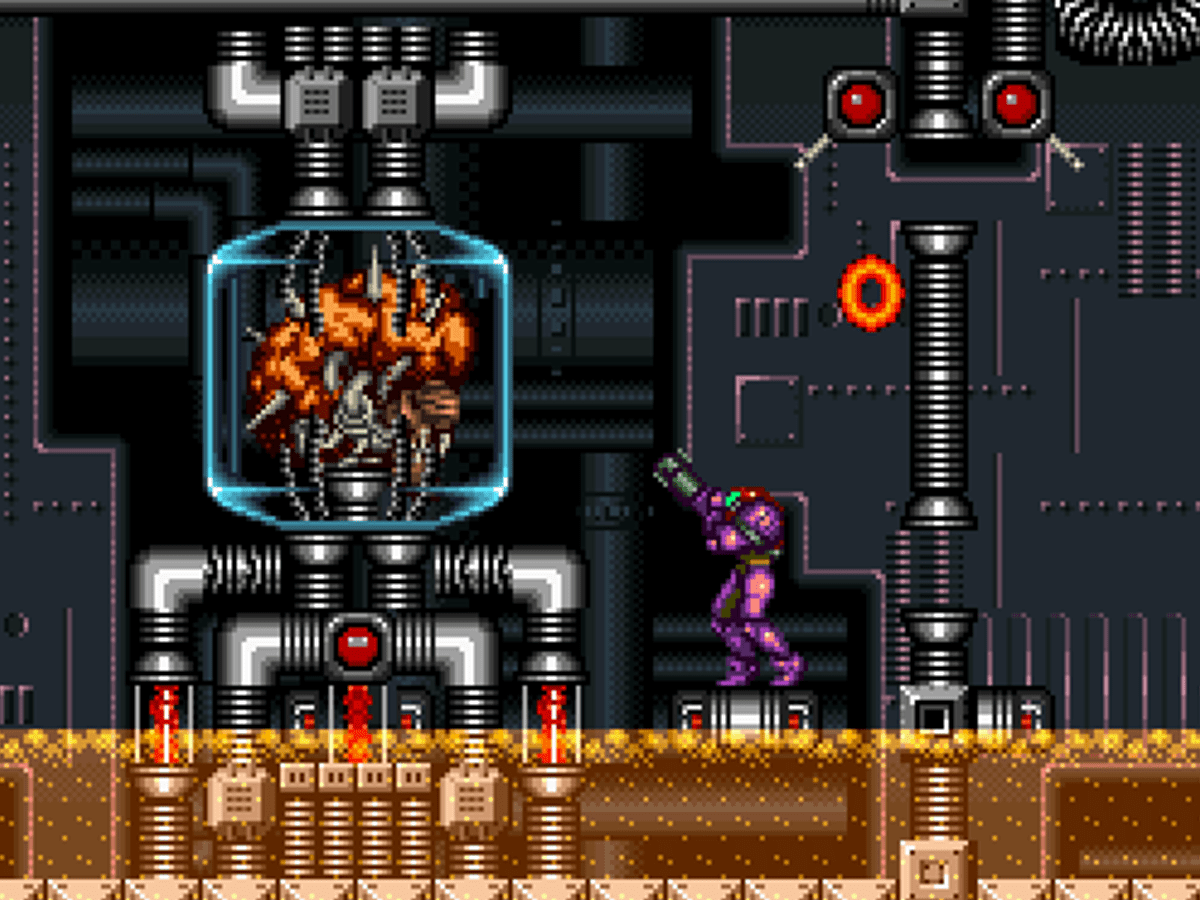

Ever played a classic game without reading the instruction manual? I recently played through the incredible Super Metroid for the first time. As a long-time fan of the Metroid series, I had a pretty solid idea of the major players, as well as their motivations. At least, I thought I did.

It quickly became apparent to me that I had no idea who a ton of the monsters were. I recognized Kraid and Mother Brain, Phantoon and Draygon required some research. Why was I killing all these aliens? I knew it had something to do with the last Metroid, but why was Mother Brain back?

I soon created my own lore for the game, with Samus putting everything at arm’s-length. She never thought about killing, she just needed to do what she had to. Samus didn’t care what an enemy was, or if it was the last of its kind, she just needed it dead.

I have no idea if that’s how the developers saw Samus. But that is how a lot of these early games function. Without the instruction manual, guide, or any other ancillary material, all you knew was what you saw. Even then, you might be seeing something in that blob of pixels that the developer didn’t intend. You built your own stories and filled these worlds with your own heroes, villains and monsters. They were games that, intentionally or not, encouraged imagination.

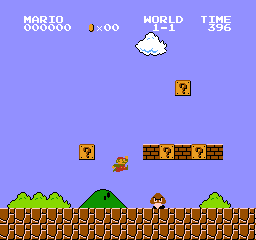

Classic games gave the player a frame to work from. Even with the details found in instruction manuals and the like, it was easy to concoct backstories and explanations for everything else in the game world. The humble Goomba, perhaps the most iconic of enemies, is never fully explained in-game. Are they actually hostile, or just some poor creature who happened in the way? To some, the Goomba may obviously be evil. It does damage Mario. But to others, its path is merely a straight line. It doesn’t seem actively hostile, so why kill it?

The SoulsBorne series has taken these, perhaps unintentional, elements of classic game design and modernized the experience. Every character in the series, good or evil, can be killed. The decision of who to kill relies entirely on how you perceive the world. The stories are vast and open to interpretation, encouraging exploration and the ability to fill in gaps with imagination.

Undeniably, games have evolved from this old style of design. They offer lush, rewarding stories with actual characters and themes. They know how to make you laugh, cry, and smile. Even in indie titles without clear characters or dialogue, games have learned how to tell stories in ways that the classics could only brush against. But there’s something to be said for allowing the player to create their own narratives. There’s a level of skill in giving the player access to all the lore they could ever want, but also allowing them to create their own.

Very few approach storytelling and world-building in the way that Miyazaki does. Few offer a puzzle that can be completed differently by every player without the developer’s guiding hand showing where all the pieces belong. Few allow room for imagination within their stories.

Bloodborne is one of my all-time favorite games. Sure, the mechanics are excellent, but what drew me in were the presentation and the lore that compelled me to lay the puzzle, read analyses and make my own decisions about the world and its story – much like Twin Peaks sparked a similar obsession in me.

Right now, I’m re-reading Gene Wolfe’s “The Book of the New Sun”, which is one of few literary works that work in much the same way. I can really recommend that series if one is interested in such narratives!