God money I’ll do anything for you

God money just tell me what you want me to

God money nail me up against the wall

God money don’t want everything he wants it all

– Nine Inch Nails (and Ashley Too)

I wrote in my piece on “Smithereens” that I love the way in which Black Mirror at times takes an old song and makes us hear it with fresh ears. This does not apply when it comes to the way Nine Inch Nails’s “Head Like a Hole” is used in “Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too.” The way it is repurposed into a pop song performed by Miley Cyrus frankly disgusts me.

But perhaps this is the point. As we hear insipid lines such as, “I’m on a roll, achieving my goals” (and cannot help but think of “Head Like a Hole”) we are subtly given the theme of the episode from the beginning, which is embodied in the lyrics of the latter, and not those of the fictional Ashley O song that we are subjected to over and over again.

And not just the theme of the episode, but meaningfully its plot. “I’d rather die than give you control”—see Ashley Too unplugging Ashley O from life support, without knowing that she would wake up. Rather, all she knows is that she would rather die than “live” like that, without agency.

The end of the episode, which sees ASHLEY FUKN O (as her name reads on the marquee) performing a version of the original Nine Inch Nails song made my skin crawl, but the structure here also gives a clear indication of what the episode was trying to do.

Ashley O is being controlled by her aunt Catherine from the beginning when she appears on a talk show and the latter prods her to plug the new Ashley Too doll. This only becomes more severe when Catherine drugs her into a coma and proceeds to use technology to mine songs from her unconscious brain.

And why? Because she serves the Almighty Dollar—the God money that she will do anything for. If she has to exploit Ashley O in the name of capitalism, so be it. She’s not Leonard fucking Cohen—who presumably Catherine respects as an artist?—she’s a pop star. It is her persona, and not her authentic self, that brings the fame and the wealth that comes along with it.

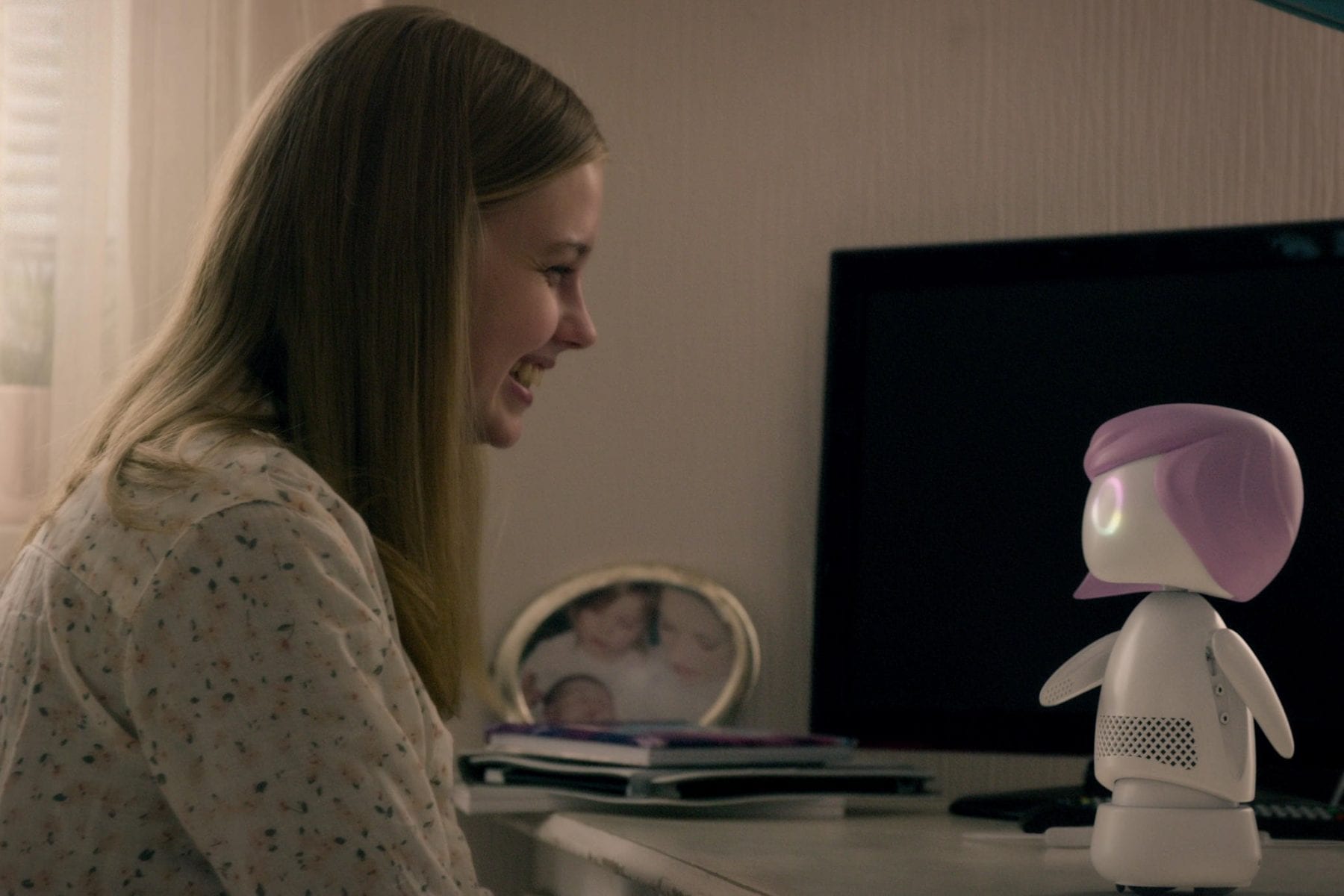

This is represented with the Ashley Too dolls. They copied Ashley O’s actual mind and put it into each one (with a limiter in place of course). We have seen such technology in Black Mirror before, but it has usually been in service of asking whether the digital copy counts as a person. That question comes up here by the end of the hour, but in the beginning Ashley Too serves another purpose.

She is a simulacrum of the real Ashley, not because she is a copy, but because of the limiter that has been placed on her. It is not the Ashley who gets depressed and feels anger that they want to box and sell, after all, but the image she presents when she puts on the costume that she says at one point makes it feel like she is wearing someone else’s skin.

“Ashley O” isn’t real—none of the pop stars or celebrities we see are, insofar as what we see is always a crafted representation. And even those who present as “authentic” aren’t really, if being so is a part of their brand (as Black Mirror explored as far back as “Fifteen Million Merits“). If you want a celebrity being authentic, it is Kiefer Sutherland drunkenly attacking a Christmas tree, but then even that got taken up into his “brand image.”

It’s all vacuous. A head like a hole thinks these things up—how to spin events, what face to put forward, how to capitalize on the misstep, etc. Believe in yourself, and you can be like Ashley, too. Just post the songs that come to you in your dreams on YouTube and you’ll be on your way.

It’s all bullshit. They—or, let’s blame Catherine, I guess—have put forward an image and a story that is fundamentally hollow: a version of the American Dream for our late-capitalist age. Could any given person make videos and become a YouTube star? Yes. Could every person? Obviously not—some of us are destined to trip and knock over the stool when we try to do a dance number.

Ashley Too is an attempt to ramp up parasocial interaction with such simulacra. She’s full of nothing but positivity, and no one is like that. But when the devices learn about Ashley O going into a coma and so on, they freak out and are recalled.

Rachel’s just happens to be off and doesn’t learn about events until an Access Hollywood style “news” report wakes her up by saying the magic words. By that point, it is not just that Ashley O is in a coma; rather, Catherine’s plans are in full swing. With the help of technology, she and others are mining Ashley O’s brain for songs in order to put out a new album. And we ultimately see what the culmination of this plan is: the holographic Ashley Eternal.

The first part of this—that Ashley is dreaming songs while in a coma that can be plucked out and packaged—is maybe the most implausible thing Black Mirror has ever suggested in my eyes, but it does give further entry into the image manipulation I mentioned above. We see, for example, what Catherine describes as a “rage dream” being altered in terms of its pitch and positivity into something that will work, providing a commentary on how music producers can move to water down the work of artists in the name of marketability.

The hologram thing, however, is completely realistic at this point, as we have already seen holograms of dead performers show up on stage in the real world. What do we think of this? Is it a tribute? Is it nice to see Hologram Tupac, or is it disrespectful and weird? Should we celebrate the way we can enjoy artists after they’ve passed through this technology, or call lawyers to secure the rights for our images after we’re dead? (And would that even work?)

Ashley Too becomes self-aware after fritzing out in response to the “news” story and Jack deleting the limiter in her brain. Then she freaks out about having a cable stuck in her ass, and, well, there is a lot that follows that feels like the kind of comedy you would expect from a kids’ movie or something like that more than you would from an episode of Black Mirror.

To be honest, I didn’t care for it, particularly on my first viewing. But when I watched the episode a second time in preparation for writing this thing you are reading, the style grew on me.

It is absurd, after all, that there would be this cute robotic doll inhabited by the full consciousness of Ashely O, and the ranting and cussing serves to drive home that point in a quick way—this is no longer the Ashley Too who is just going to tell Rachel to “believe in herself” but a copy of the real person, with all her spite and angst.

The jokes about her not being able to open doors and the like follow, and perhaps the form was also meant to help land the overall theme of the episode. If these seemed like the facile jokes of a children’s film, perhaps that is to signal that we have not escaped the spectacle. We have merely entered an apparent subversion that continues to subsist inside of it.

Ashley Too, along with Jack and Rachel, frees Ashley O from her medically induced coma. They help her to crash Catherine’s event unveiling Ashley Eternal, and we get a satisfying moment wherein Ashley O, adorned only in a medical gown, flips her aunt Catherine the bird.

And then she performs the real version of “Head Like a Hole.” Are we to believe that she wrote it in the universe of Black Mirror, playing off her own earlier insipid pop song? Or are we to think that the Nine Inch Nails song exists in this universe too, that her pop song was copying it, and now she is covering the original?

Either way, this performance at the end of the hour is derivative, either of her own work or of that of another. The idea that she is covering NIN is actually fairly boring, though, so let’s consider the other option.

If the idea is that now Ashley O, free from the constraints and manipulation of Catherine, is being her authentic self, what does it say that her new song is just a version of the old one with darker lyrics and tones?

A couple of her fans run from the small venue, but isn’t the more warranted conclusion in the other direction? “Head Like a Hole” basically is a pop song in its beats and rhythms—there is a reason it mashes up so well with “Call Me Maybe.”

There is also the tone, sure, but if that is dark on Pretty Hate Machine, it really isn’t here. Here it is performed as a pop song. This is what it would look like if someone performed the song on American Idol. Thus that the young women who have presumably long been fans of Ashley O run from the venue is wildly implausible, particularly since people don’t listen to lyrics.

But it is Trent Reznor’s lyrics that bring the point home, and I understand why the episode ends in the way it does. They are about how everything gets subordinated to the almighty dollar: health, self, autonomy…and while “you’re going to get what you deserve” can stick in your head as though it is some kind of empowering anthem, it isn’t. It is ironically playing on the idea that capitalism is a meritocracy. The God that is Money will make sure you get what you deserve. Don’t worry. He doesn’t want everything, he just wants it all.

I’m really surprised by all the critical hate for this episode. I thought it was a much-needed delight in this current political climate. It was a Disney movie parody, structurally and tonally, complete with Hannah Montana. And I really don’t get why folks are all twisted up over the use of “Head Like a Hole,” which had Trent Reznor’s blessing (NIN even has a tie-in t-shirt for sale). The melody is immediately recognizable to the show’s target audience and prompts a WTF reaction everytime it plays. I thought it was clear it’s not a NIN song in universe (because copyrights). “I’m On a Roll” is the original Ashley O release. “Head Like a Hole” is her remix, which she says she wrote about her aunt. So I think we take that at face value rather than look at it as social criticism. This is a Disney movie, after all, with a happy ending for all the Britneys, Lindsays, and Mileys out there.

Yeah, I feel like I am not as down on it as a lot of things i have seen. I liked it more the second time I watched it, and even more as I wrote about it. I would hope that maybe reading this would help some people appreciate it more.

At the same time, I wanted to be honest about my reactions. I know that Trent gave his blessing for them to use the song, for example, but that doesn’t change my negative aesthetic reaction. Conceptually, I have a line on what I think they were doing that I tried to articulate here, and I think the episode is far more interesting than what I have seen a lot of people saying about it. But I still hate the Ashley song, viscerally.

Same goes when it comes to the Disney movie kind of style. I think what they were trying to do is interesting conceptually, but I still don’t care for it on a more gut level. That’s what I was trying to get at in the piece here, however successfully or unsuccessfully I ultimately did so.

And a lot of this comes down to the fact that I don’t like pop music or Disney movies, I’m sure. But I have seen some articles online calling the episode dumb, etc., and I do not think it is that.

I can respect that. I’m not a fan of pop music or Disney movies either, but I do appreciate the way they picked their genre and ran with it. And I thought Miley Cyrus was great, though I’ve never seen an episode of Hannah Montana. Ashley O and unfiltered Ashley Too cracked me up.