It’s beyond cliché to start an exploration of any topic by referring to the dictionary. So I hope you’ll bear with me when I tell you that Merriam-Webster’s defines “history” as “a chronological record of significant events often including an explanation of their causes.”

I start with the cliché because it’s the understanding most of us have of history. But it’s not until you’ve gone through the nine other definitions in that dictionary to find one that’s actually broad enough to capture the word in its plainest, most essential form. History is, most simply, “events in the past.” Granted that broad a status, any events – no matter how large or small – fit into the concept of history. Ancient history. Personal history. A history of substance abuse. They’re just things; wayward nouns stuck in some backwards line of time.

But what if you could unstick those objects from the firmament of time and play with them?

Most entertainment media answer this question through the conceit of time travel. It’s the subject of countless pop-culture products: movies like Back to the Future, television series like Netflix’s Dark, and book series like Outlander, just to name a few. Video games have long offered their own take on the time travel phenomena, but most of these have either been in the service of a linear, single player narrative (see Chrono Trigger), or have used time travel primarily as a device for developing gameplay (see Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Turtles in Time for a similar era comparison point).

For a medium uniquely positioned to disassemble the rules that bind our experiences with our histories, video games have not widely provided freewheeling opportunities for players to reconsider and rebuild history.[1]

Except, that is, for one set of games. The historical Grand Strategy Game genre has ventured into this realm of playing with the world, summarizing a set of rules derived from real-world experience and then leaving the player to interact with those rules, allowing them to reconstruct the world into a shape of their choosing. Grounded in world history but willing to play fast-and-loose with historical plausibility, they give players the chance to imagine histories entirely divorced from reality and then make them real.

Grand Strategy Games – A Primer

So what is a Grand Strategy Game (GSG)? Put simply, it’s a real-time, often pausable, strategy game, that lets you control a political entity and lead it to control over a portion of some sort of map interface.

If you’ve never played computer strategy games before, think of it like the classic board game Risk. Except instead of taking turns to roll dice and attack other players, everyone is rolling dice and attacking and defending and collecting cards all at once. And instead of being an ambiguous colour spreading over the map, you as a player are usually representing some sort of political establishment–either a country on the map of Earth, or some sort of interstellar empire spreading across the known or unknown galaxy.

Risk is also a good comparison point for the historical GSGs closest competitors, which are some of the most widely-played strategy games on computers and consoles. In particular the so-called 4X games. These titles, which focus on exploration, expansion, exploitation, and extermination (for 4Xs), are a good counterpoint to describe GSGs, and probably the most famous of 4X games are the Sid Meier-conceived series Civilization.

In these games the player starts off as a settler on an Earth-like map, founds a civilization, and then performs the 4Xs until they’ve conquered the world through military, diplomatic, or technological means. Or until they’ve lost the game to the computer (or another player) also pursuing the same goals. Players and the other AI-controlled factions on the map take turns capturing resources, building up cities, and fighting battles until a winner is declared. Just like Risk, a lucky starting position, some good timing, and a bit of strategic foresight can see you through to victory. And just like Risk, each faction starts off more or less equal–a symmetrical game where no one civilization is intrinsically disadvantaged over another (those lucky starting positions notwithstanding).

Civilization is not concerned with historical plausibility. Nominally grounded in our world and its course of time, each “civilization” the player can control is based around a historical nation or ethnic identity, develops along a set technological path, and features units unique to its history, such as conquistadors for Spain, or U-Boats for Germany. But the games provide an engaging experience for the player by fostering the desire to play “just one more turn” over and over again by offering the player a continual stream of rewards and new mechanics. Each time the player concludes their turn, the time dial moves forward (sometimes a hundred years, sometimes just three or four) and they are awash with their next scientific discovery, or the emergence of their first great artist, or the geopolitical backstabbing of India, warmongering purveyor of nuclear devices.[2] The result is that, though the games usually start in the distant year of 4000 BCE, by the 1400s a talented player can control tanks and a fully-functioning air force.

In contrast, historical GSGs are asymmetrical, set within a specific scope of time, and far more historically grounded. While not designed to be historical simulators (though some games have hewn closer to this than others), most GSGs nonetheless provide a slew of mechanics to try and restrain gameplay within bounds closer to real world history. Which is not to say GSGs do not allow for wildly ahistorical outcomes. They do. But they provide abstractions, grounded in the real world, that force the player into finding inventive ways around these historically-based rules.

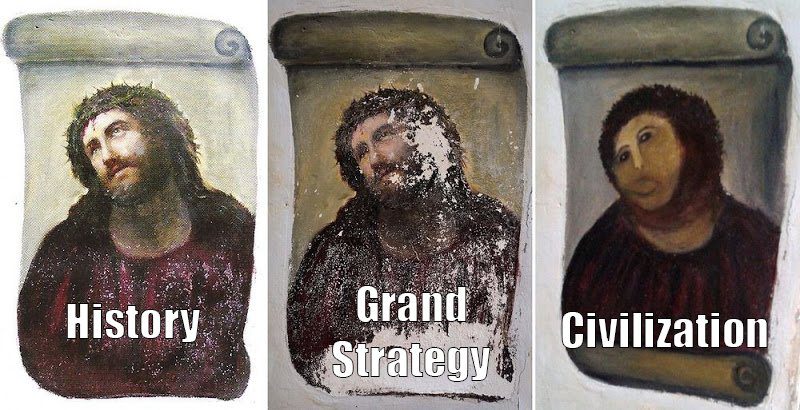

If historical accuracy and authenticity within computer strategy games were to be portrayed as a spectrum, this meme probably summarizes it best:

Historical GSGs do away with the idea of abstracted turns, instead grounding the passage of time within the game to the historical calendar of the period being described through a series of “ticks”. These ticks can vary in scope but in most games they cover a single day and the passage of time can be sped up, slowed down, or paused altogether in order to allow the player to control that passage to fit their needs. If you are leading an army in an intricate battle with your neighbours, you can move time slowly to issue orders as the war goes back and forth. If you are waiting patiently for a truce to run out so you can invade your neighbour one more time, you can run it quickly. Pausing the game altogether allows players to plan their next conquest or set in motion a series of diplomatic overtures. This tick system provides a certain grounding to the sense of time players engage with in the game–the number of ticks are set from the beginning, a hard boundary on what can be accomplished within the scope of the title.

Aside from not being turn-based, the asymmetry of a GSG is also an important distinction from similar strategy games. The experience of playing as one country is often wildly different than playing as another because the historical realities of these two countries are inherently different. The situation of the Ming Empire in the year 1500 is inherently different than that of an Indigenous tribe on the plains of North America in the same time period, for instance.

In the spectrum of historical simulations between 4X strategy games and historical GSGs there’s another entry worth noting: Creative Assembly’s Total War. Those games combine the turn-based structure of Civilization and its city-building economy with real-time battles that provide something closer to a firm sense of realism than the highly abstract “Warrior” versus “Musketman” clashes from Civilization. The Total War series also places a set of restrictions on the player to ensure a degree of historical accuracy, mostly by focusing on one historical period of conflict (the rise of Rome, the Three Kingdoms period of ancient China, Attila’s invasion of Europe, etc.). But the games have also focused exclusively on the “Total War” concept of the title, pushing things like plausible diplomacy, meaningful economic development, and larger geopolitical ramifications, to the side in favour of all out war and controllable battles.

A Paradoxical Start

So with that picture of GSGs in mind, let’s talk about some concrete examples. And when you go looking for concrete examples of historical GSGs, one name will always come up, because it turns out one development studio has a near monopoly on the genre. That company is Paradox Interactive.

While not the only producer of GSGs, Paradox Interactive is by far the largest and most successful, and their games are widely considered the high water marks in the genre. The studio has developed and published a series of GSGs, and from their names alone–titles such as Stellaris, Crusader Kings, Victoria, and Imperator: Rome–it’s easy to see that each game takes a similar approach.

Each Paradox title builds a set of systems that allow players to partake in a historical (or futuristic) political sandbox. The focus on fleshing out system mechanics that bring the particular time period to life allows for not just the kind of restrictions that a game like Civilization lack, but the depth and breadth that makes multiple kinds of gameplay possible (which Total War, for example, has long lacked).

In Victoria 2, for example–a game which focuses on the time period from 1836-1936–mechanics are in place to represent the balance of power in Europe, to simulate the “Scramble for Africa”, to show the rapid industrialization of the world, and to model the spread of nationalism. That wide variety of mechanics means a player has several options open to how they play the game and control their political entity (in this case a nation). The player can try and warmonger their way into conquering land or establishing colonies, with the game challenging them to ensure they don’t anger too many other countries and wind up the target of a retributive war. Just as easily they can try and play pacifistically, focusing on improving the literacy and quality of life for the citizens in their country, peacefully adding other countries into a sphere of influence to gain access to their resources and markets. A player can try and install communism or liberalism in their own country or in surrounding nations, even in those that historically refused them. The result is that a world that looked historically accurate in 1836 will look nothing of the sort by the time the player is done, even if the numerous countries controlled by the AI behave more or less historically (which is rarely the case).

From that brief overview alone (realizing that touched on only a few of the mechanics Victoria 2 has on offer) it should be clear that historical GSGs offer not just multiple approaches to managing one’s player country and engaging with AI-controlled opponents, they also threaten to drown a player with information.

A game like Europa Universalis IV, which covers the global ages of exploration and Empire-building from 1444 to 1821, has so many interlocking, one-off gameplay factors to consider–Aggressive Expansion, Overextension, Religious Unity, Army Professionalism, War Exhaustion, to name just five–that the game builds its own lexicon into which players are deposited, like a tourist in a foreign country. Upon each of those factors are numerical figures that combine, subtract, multiply and divide in complex ways, such that playing the game can seem to require a degree in statistics just to understand what’s actually occurring under the hood. What has made Paradox GSGs noteworthy is that they don’t hide these complicated features, but have found ways of making them transparent and manipulable to the player.

Upon all this complexity though, is a simple premise: you are the master of a demesne (or domain, if you’re not down with feudal European terms), in charge of its growth or destruction, bound to certain historical rules but free to test, play with, and inevitably, break them.

The Two Player Problem

It’s the interaction between those two poles of the game–the complex mechanics and the historical boundaries–that provide the majority of the attraction to the genre. While most players seem to enjoy both aspects of the game, the player base can be crudely broken down into a spectrum of fans sitting in appreciation somewhere between those two poles.

On one end you have what I’d call the pure gamer who enthuses most of all in the “min-maxing” of the game, of pulling apart the complicated interconnected sets of features and finding ways to break the game. They will do incredible things like conquer the entire world as the tiny Ryuku islands or win World War 2 as Luxembourg, Bhutan, or Tannu Tiva. As a gross overgeneralization, these players seem less invested in the historicity of the games–and more concerned with the game mechanics themselves.

What GSGs offer these players in particular are the asymmetrical starting positions and random AI inflection points that grant each nation, or each character, or each setting, a unique challenge. The result is an almost infinite replayability. These players will often revel in the challenge presented and allow the historical aspects of the game to act as mere flavour. They will play the game without any sense of historical plausibility to tie them down, with spreadsheets and calculators readily at hand to crunch the game’s mechanical readouts and a relentless drive to exploit the loopholes present in the code. These players explore and conquer the invisible “metagame” that other players may only tangentially interact with, getting the maximum for their political entity with the minimum of resources, or “min-maxing” the possibilities present in the game’s mechanics.

The min-maxer of the GSG is a unique creature and, as with all of the internet’s many unique habitats, YouTube provides a gateway into the sub-niche in question. To give just the tiniest sense of the lengths these players will go to achieve the greatest feats in the game, I offer up this video of one YouTuber, Arumba, who talks for eight minutes about his reasoning behind making a single decision related to what resource he should trade for in the recently released Imperator: Rome. It’s quite something to see the math laid bare, but more interesting to watch the thinking that goes into it:

On the opposite end from the min-maxer you have the historical and role-playing aficionado. For these players the altered, sometimes random, often-wacky unfolding of history is the prime goal of the game. The game mechanics themselves, while engaging, may actually get in the way of achieving the desired end-state or exploring the process of the imagined history. These players, too, might look at tiny Ryuku (modern day Okinawa islands) and decide there is room there for historical improvement, but theirs will be focused on perhaps a specific goal, a specific question: what if the Okinawans invaded Japan? So their entire focus will remain on this one goal, the joy of forming the alliances required and chipping away at the Ashikaga shogunate, until the historical conqueror is, itself, conquered.

With entire continents to explore across multiple time periods and with different mechanics in each era, the possibilities to reshape history and answer the questions posed by a player’s imagination are almost endless. What if the Eastern Roman (a.k.a. Byzantine) Empire never fell? What if Germany and the central powers had won World War One? What if William the Conqueror had failed to conquer England? What if the Aztec empire had actually invaded Europe in a reversal of the colonialism we experienced in history?

The games allow the player to answer these questions in a dynamic way, bound by the mechanics that the min-maxers exploit, such that the answers constantly border on the possible. That plausibility gives a weight to the player’s actions, reinforcing a sense that–but for the player’s agency–history would unfold very similarly to how it did in the real world. When a great change is to be found in the fate of a nation or political dynasty it is the player’s doing. They are rewriting geopolitical history to their own design. Or, sometimes, as an extreme counterpoint to the minmaxer video above, “playing” only in the loosest sense, instead simply observing an alternate history unfold in its unpredictable, sometimes awkward glory.

For these players the distinct appeal of the games is primarily to live in interesting times without having to live in them at all. To partake in the sweeping changes of the renaissance or the misery of medieval plagues from the comforting distance of a semi-omniscient overlord, pleasantly awash in easily defined values to be manipulated and contorted to their own purposes. The player can be separated from the realities of the stories created by them through sheer scope and grandiosity. The deaths of a long, torturous war are abstracted into a generic “manpower” figure, which magically reasserts itself after a few hundred ticks regardless of the outcome of the war. The bankruptcy forced on a rival is a useful way of disarming them from future aggression, not the condemnation into starvation for thousands. The encirclement and eradication of twenty divisions of the Red Army in 1942 is an important step towards defeating the Communist menace, not a heinous war crime (prisoners are not one of Hearts of Iron’s mechanics).

Rhythms and Victories

While crudely clumping the playerbase into two different extremes is useful for illustrative purposes, it should be made clear that relatively few players actually stick to either extreme. Even Arumba–the min-maxer pointed out above–is well known for his Crusader Kings 2 playthroughs. These videos, where he role-plays some obscure lord from the medieval ages and gets him or her into absurd situations, rely on his min-maxing skill only to extract the character from said situation and continue the game. The purpose of painting two extremes is to illustrate the breadth of players interested in these games.

So what is it about these games that appeals to this wide range of the gamer community? Why can both history nerds and strategy nerds lovingly dote on, roundly criticize, and avidly discuss these games–sometimes all within the same online breath? What is the experience of playing one of these games?

Historical GSGs build upon the central conceit of “one more turn” baked into the 4X Civilization games, amplifying and morphing this factor with each game’s own peculiar logic. At almost any point in one of the games, there are dozens of possibilities about what to do next, based on the twists and turns in AI choice, player choice, historical background, random chance, and evolving game mechanics.

The “pause-and-play” mechanic of GSGs, in particular, contribute to this super-powered sense the player builds of needing to just do one more activity. When you’re just waiting for a historical event to come, such as the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, you can speed through the game’s ticks at light-speed, then slow them down again when you’re coordinating the Soviet response to this invasion. Whereas Civilization and Total War require a series of lengthy turns to wait until the next important event, these passages of inactivity can effectively be skipped over by the player in a way other games can’t manage.

The result is that the player eventually enters a fugue-like state, skipping forward, pausing to consider, then picking up at the right pace for their next decision, the real-time duration between major choices spread out as evenly as possible. There is no real break in the experience of playing a GSG, few natural distinctions between one tick and the next, and provided with a slew of choices in how they can interact with all the myriad gameplay functions–sometimes small and insignificant, sometimes massively disruptive–the player can quickly lose hours driving history down one path or another. It’s not uncommon for players to have dedicated hundreds, if not thousands of hours into one or more historical GSGs.

And somewhere in the middle of that unceasing stream of pausing, reading, considering, and clicking, the games develop a particular rhythm. Players of Crusader Kings 2 will grow accustomed to their avatar’s children coming of age and requiring marriages in batches, teaching the player that a few extra seconds finding the right spouse can make the difference between success and failure for the next generation. Hearts of Iron players will learn the right moments to pause in the buildup to World War 2, so that they might ideally develop their nation’s industrial capacity. Europa Universalis IV acts like an ocean tide, with ebbs and flows of the player nation’s fortunes, from the joys of conquest to the inevitable desire for the conquered people to return to their homeland in the form of annoying, sometimes dangerous, separatist rebels. Each playthrough is similar in structure, but different enough in detail, to drive a sense of novelty amidst familiarity–punctuated by small, direct doses of dopamine when a goal is achieved, a victory grasped.

And it’s those victories that elevate the game above the mere tactical joys of watching your country defeat another in battle. Win enough of those battles and you’ve won the war. Win enough wars and your once-formidable neighbour will be ground into dust. A player will emerge from the rhythm of pauses, clicks, and decisions, to find that they’ve reshaped an entire world.

Our world. Except no longer ours at all. A new one, familiar but twisted by the player into something else.

The Stories of Histories

Different players, obviously, place different levels of emphasis on how that world will look. The extreme min-maxers, for instance, don’t really care about any of the real-world implications of leading one country to greatness over another. But there are others for whom the goal of shaping the world to fit a preconceived notion is a large part of the appeal.

As one might expect amidst games that can’t help but glorify history to an extent, the games do have a natural gravity for those who view the past as an ideal; as a golden age. Though not a majority of the community by any extent, there are those for whom those historical ideals consist of a rejection of one aspect or another of the modern world, opting to return to a time when another set of worldviews were more acceptable.

Perhaps the most obvious example of this is the rampant presence of many Hearts of Iron players openly espousing Nazi rhetoric. Really any game that allows you to play as Nazis is likely susceptible to this, but Hearts of Iron multiplayer servers are notorious for running rampant with players who parrot alt-right talking points, if not outright Nazi-era racism and anti-Semitism.

Similarly the Crusader Kings 2 community is prone to the “Deus Vult” memes that glorify the Crusades, usually (if you can use the term) innocuously, but sometimes with an explicitly Islamaphobic angle. That the Crusades are in the title of the game actually overstates those wars’ importance in terms of gameplay, but for the sometimes vocal, oftentimes small playerbase that plays the game explicitly in order to fulfill fantasies of a clash between “Western” and “Islamic” civilizations, there’s nothing more important than the Crusade mechanics.

Sometimes these bastions of bigotry are better hidden. A common refrain amidst the Europa Universalis community was to refer to the Ottoman Empire–one of the strongest nations to play as at the start of the fourth game–as “the kebab.” This rather crude signifier for the political entity of the Turkish people could appear to a newcomer rather benign, perhaps just another entry in the long list of lexicon mentioned earlier. But when one considers the primary use of the term was to “remove the kebab,” in effect to wipe out the Ottoman Empire entirely, that it took on a deeper meaning. A meaning that reared its head deeper in conversation threads, when the phrase grew to show its true meaning amongst some players as a stand-in, once again, for all Muslims. It wasn’t until the Christchurch mosque shooting that Reddit’s Paradox community, for instance, instituted rules banning the use of the phrase.

Such ugliness is a natural offshoot of the game, and for those with different political interests the options to reshape history can also be a key attraction to the genre. Speaking for myself, I have only ever won World War 2 as Nazi Germany once–just to see if I could–after playing Hearts of Iron games for nearly 500 hours. I have, however, won an alternate World War 2 as a democratic Germany more times than I can count. I even developed a mod to shape that democratic Germany into the particular shape I wanted to see.[3] No matter your political stripe, the games act as geopolitical wish-fulfilment. The opportunity to recreate the world into the shape you desire is part of that larger sense of victory achievable by the player, and a key source of the game’s appeal.

The Personal is the Political

That possibility of staring at a map and seeing the choices the player has made, expressed in a tangible form, is an element that gives historical GSGs their sense of completion. The same way fighting games have ranked ladders and tournament outcomes to show where players stand in the game’s hierarchy, the way First-Person Shooter games have lifetime Kill:Death ratios to show player skill, the way RPGs have multiple endings and achievement statistics to explain the depth of the world the player has explored. These historical GSGs offer a sense of growth at the end of each game–whether successful or not–that the player has left their mark on history, gone back into time, and created a new chronicle.

Just as those games offer their own unique attractions–to fight in a war from the comfort of a chair, or to explore strange new worlds and save them from the forces of evil–historical GSGs offer the chance to rewrite history. And who doesn’t have parts of their history they wouldn’t rewrite? Choices they might have done differently? Choices they may have never had to make if someone else’s choices were made differently?

Our personal lives often play out in random, unexpected, sometimes calamitous ways. There are forces, seen and unseen, that give our lives their own rhythms, and we make our small choices along the way to guide and shape our eventual conclusions. Real life, and our remembrances of it, is in many ways the opposite of these games. An experience writ small what the game writs large: to imagine that the turning points of a personal history could be defined by a clash of civilizations, managed and beaten through diligence, planning, and a bit of luck. It offers a counterpoint to reality, a dream – that maybe real life could offer as much transparency in how the world views you, what your goals should be next, how easy they might be to attain, and what steps you can take in the interim. The games are sandboxes, like life, but where the consequences aren’t crippling, and the opportunity to fail and learn from that failure is built right in.

Like so many other game genres, the Grand Strategy Game offers an escape. But more than that, it offers a prism, a geopolitical and historical stylus with which to write a grand narrative amidst a system of structured chaos. The world is yours to do with as you please, and history–that long chain of events, of things, stretching back as far as we can collectively remember–is something that can be grasped, held, and played with. It’s no longer something to which we are connected, it’s something we’ve constructed.

And that’s a welcome experience. In a world that seems to constantly challenge us, where each challenge seems predestined based on the billions and billions of decisions that predated our own, the fantastical escape of reforming the entire world to another possibility is a unique joy.

[1] The exception, besides the one discussed for the rest of this essay, is likely Quantic Dream’s series of relatively open-ended narrative games such as Heavy Rain, Beyond: Two Souls, and Detroit: Become Human, which also provide the player with many different ways to succeed or fail, adapting to those successes and failures while offering a sense that the world continues regardless of the player’s actions.

[2] India’s status as a warmongering nation in Civilization is owed to a quirk of programming in the games’ earliest incarnations. Essentially India’s AI-controlled penchant for war was set at an integer of 0, representing Gandhi’s well-known pacifism. A technology later in the game would lower this number by 1. However the programmers forgot to set up a check to ensure 0 was the lowest the number could go. Instead India’s aggression backflowed to the highest number possible: 255. And AI-controlled India began spreading nuclear bombs over the world.

[3] The modification community for Paradox’s GSGs are worthy of an essay all their own. They offer near unlimited possibilities for players to not just ask historical questions, but answer them as well, beyond the limitations the game’s original designers have intended.

Great and informative share.

Great and informative share.

An essay every gamer should read.

An essay every gamer should read.

Great Article! I’m a EUIV enthusiast myself, so can feel it 🙂 I’d like to point out, that there’s another contender to the grand strategy genre, maybe leaning a bit more to the total war side however: Hegemony III: Clash of the Ancients is a strategy game set in ancient Italy that let’s the player experience what it was like to thrive in the ancient world and what it really took to form Rome into an Empire.

Great Article! I’m a EUIV enthusiast myself, so can feel it 🙂 I’d like to point out, that there’s another contender to the grand strategy genre, maybe leaning a bit more to the total war side however: Hegemony III: Clash of the Ancients is a strategy game set in ancient Italy that let’s the player experience what it was like to thrive in the ancient world and what it really took to form Rome into an Empire.