When we first started talking about end of the decade coverage, I said that I didn’t feel like I had much of a sense of this as a decade. Certainly I don’t in the same way as one might for various decades in the 20th century, from those I lived through (the ‘80s and ‘90s) to those that I didn’t. Is there a zeitgeist that defines this span of 10 years?

I started thinking that perhaps it was the very lack of such a unifying spirit of the times that defines our present age. It’s not exactly a new thought for me, but one that I hadn’t really related to whatever we’re going to call this decade of the 2010s explicitly, even in my own mind. There is a way in which everything has become dispersed. “Must-See-TV” and radio stations have been meaningfully replaced by the internet, where each of us can seek out the media that we want to consume, rather than relying on the big broadcast networks and stations for access.

I remember as a child waiting for a song to come on the radio so that I could record it onto a cassette tape. I imagine this experience might strike the youth of today as inconceivable.

World Serves Its Own Needs, or We “Aught” to Have Seen It Coming

The movement I’m thinking of was already in swing in the aughts, of course. As pop music in the old style died, shows like American Idol arose to provide a simulacrum of it. We began voting on what would be popular, which then became popular because we had decided it would be. The door to a phenomenon such as occurred with Nirvana (or even The Beatles, honestly), silently edged itself shut.

But the aughts demanded at least this simulacrum—something holding the space of the popular music/TV that “everyone” consumed, or at least knew about. Now, people will mention a pop artist and I will often have no clue who they are talking about. I learned who Ed Sheeran was when people got in a tiff about him being on Game of Thrones. And the truth is, I feel perfectly fine about that. It could be because I’m getting old, but I sort of don’t think so. The younger people I interact with equally seem to have no interest in knowing about something unless it interests them. And at least in some regard, I think this is to the good. But there is a dark side to it, too.

What’s happened I think can be meaningfully tracked through certain technological developments and how they have impacted our experiences as music listeners, television watchers, etc., over the past decade (or so). It’s easy to lose sight of how quickly certain things have happened.

Dummy Serve Your Own Needs, or The Rise of Social Media and Smartphones

While now it seems like pretty much everyone has a little computer they call a phone, the iPhone (the first smartphone of significance) was released only in the summer of 2007. Netflix began streaming services the same year, with Hulu to shortly follow (YouTube came a year or two prior). Of course, all of these dates are in the 2000s, but it wasn’t until after 2010 that each of these things became pervasive.

When I broke up with a longtime girlfriend in 2010 and moved into a place on my own, the decision to “cut the cord” and just rely on streaming felt on the cutting edge. I didn’t have a smartphone, or, well, I had technically just gotten one, but it was some PalmOS that I don’t think exists anymore. When I spent the night at the NYPL the following year, it didn’t really count because it couldn’t scan QR codes.

It wasn’t long, though, until it started to feel like everyone had either an iPhone or an Android (or a Windows phone there for a minute). One of my buddies stuck with his old flip-phone until mid-decade, past the point where that started feeling weird, and frankly part of me wondered whether the fact that he’s Dutch was of any relevance.

Now, walking around New York City, it seems like virtually everyone has a smartphone in their hand, if not their face in the screen. It’s like we’re tethered to these things, and if the battery dies or something else goes wrong, one can feel strangely unmoored.

Along with this we have seen the rise of social media. Once again, sites like Facebook and Twitter pre-existed this decade that is now coming to close, but it was the rise of the smartphone in the 2010s that gave them an almost ubiquitous presence in people’s lives. Going to a website is one thing; getting an alert on the device in your pocket is another.

All of this has changed how we consume media, how we watch TV, and how we relate to it and one another.

World Serves Its Own Needs, or Impacts on TV

Some people (who aren’t me—though I did watch Black Mirror: Bandersnatch that way the first time because of circumstances) watch TV shows and the like on their phones. It seems even more common to do so when it comes to things like YouTube videos, and there are indications that kids today are perhaps more likely to watch such short content than they are longer-form works. We’re seeing the rise of TikTok, which I hardly understand, so it’s just getting a mention here, but I’d mark this as something to pay attention to in terms of where we might be going in the next 10 years.

Of course, at the same time, the medium of television has been opened up by the age of streaming. A clockwork show like Breaking Bad—where one absolutely cannot miss an episode—was a hard proposition even 15 years ago. By that point, one could rent DVDs of TV shows, though I’m not sure how common of a practice that was. But to have the whole thing available to stream at whatever point meant that showrunners and networks could stop worrying about those questions of access. Miss an episode? Well, go back and watch it. (It was around this same time, in the mid- to late aughts, that cable networks started offering things “on demand.”)

And so, the 2010s moved us in two conflicting directions at once: one toward ever shorter and easily consumable content, and the other toward sprawling works that have to be taken as a whole, can innovate in interesting ways, and have changed the conception of television.

These trends don’t exclude one another, but their confluence can be strange. When Game of Thrones was coming to an end, for example, there seemed to be some people who hadn’t watched the show to that point, but who wanted to be a part of the cultural moment, and thus just watched a recap of the previous seasons on YouTube or something before engaging with the end along with the rest of us.

I pass no judgment on this—though it is not something I could imagine doing myself—but point to it as a possibility in today’s world that didn’t exist before. We have the easily digestible and the long-form (and the easily digestible version of the long-form). Should I watch the presidential debate, or just the highlights later? What do I lose if I do the latter, or watch that Game of Thrones recap instead of seven seasons of the show? Perhaps it has always been thus to a certain degree, but it increasingly feels like those who have just read the CliffsNotes feel like they have as much right to speak on things as those who’ve read the novel. (And the same goes for those who form opinions based on snippets of interviews that get worked into headlines when they haven’t read the interview itself, etc.)

And to what extent do we even hold TV in common anymore? Friends recently turned 25. I never liked Friends. I mean, it was OK and I wouldn’t object to Friends being on in my presence, but I don’t think I have ever really watched Friends on purpose. But I definitely saw it when it was on the air. It was unavoidable. Everyone saw Friends. The idea of someone who had never seen Friends was inconceivable, unless they were Amish or something.

Nothing is like that at this point. Game of Thrones may have felt like it came close, but only within a certain bubble. I’m pretty sure the most popular show this decade was NCIS. And yet, the end of Game of Thrones does feel significant to me as we mark the end of the 2010s. I think it was maybe the last show that it will feel like “everyone watches.” This is the end of the water cooler TV show. I doubt that anything will draw as many people together again. Because now we can all just watch what we want to watch, and it’s all dispersed on this flat surface of the internet. I can go between that most recent episode of The Righteous Gemstones and an old episode of Futurama, and so can you.

It’s great in a way, until you realize it contributes to the increasing fracturing of our views of reality. It’s easy to focus on differing news sources when it comes to a concern about internet echo chambers, but differing entertainments surely play a role here, as well.

Listen to Your Heart Bleed, or Social Media Influence on Content

One striking thing we’ve seen in recent years is the role that social media can play in influencing what we see on our screens. There are the stories of beloved shows being saved, of course, and the failed attempts at such, but there are also those who have been negatively affected.

Roseanne Barr lost her role on the reboot of Roseanne because she said racist things on Twitter, for example. We could debate whether this was justified or not, but my point is more about the kind of influence that viewers/social media are now able to exert when it comes to what airs and what doesn’t. It’s not absolute, of course. As much as we want them to #SaveTheOA, it doesn’t seem like it’s happening. But the very fact that there is anything like this is novel. This was not a thing 10 years ago.

“Cancel culture” has been overblown, or at least concerns about it have been. But the very idea that the audience could influence things in this way is new. I guess we could always write letters to the network, but then only the network could read them. My tweet is open to the world, and when things get trending they can seemingly decide the fate of a show, or an actor, etc. Whether this is a good thing, a bad thing, or a mixed bag, it has changed the relation between the producers and consumers of content in a way there is no going back from. Those who resist are reactionary even if they are right—the only way out is through.

Feeling Pretty Psyched, or A Brave New World for Capitalism

Of course, at the same time, these companies are collecting data about everything we do. This is what we signed up for. The 2010s saw the rise of what people at one point were calling Web 2.0, but which we now probably just think of as reality—personalized advertisements, and all of that. Perhaps there is some benefit. Netflix thinks I will like this or that, and honestly, they don’t tend to be wrong. But at the same time, their original content has veered increasingly into this terrain of making things they think will do well based on their algorithms. Whereas it seemed at one time they were giving a shot to experimental shows like BoJack Horseman or The OA, now they are cancelling those while renewing Another Life.

Why? Well because they have determined that this is the kind of show that people will watch. Identify a super-specific genre, like “Sci-Fi Shows with a Strong Female Lead,” and then make one of those. Find an actor people know, or more than one, and run with it. This is the business model at this point, and it makes sense. They stopped caring about their star rating system long ago, and at this point I’m not sure if it even exists. I might give the full rating to Tarkovsky, but Netflix knows I’m sitting over here watching Supernatural. So maybe I might enjoy The Vampire Diaries?

I Feel Fine, or Entertainment and Echo Chambers

While all of this is fine and good from a certain point of view—after all, I want to watch things I like and if they are helping me find things I like, that’s cool—at another level it feeds into a more general problem, which is (at least) twofold.

On the one hand, it can feed into that worry about echo chambers, or bubbles. You read Breitbart and watch Duck Dynasty, while I read Jacobin and watch Mr. Robot. This is a problem insofar as our views of the world can diverge more and more. It’s one thing to have differing values; it’s another to have differing ontologies. And it seems to me that this is what has occurred: we no longer all live in the same world or share the same sense of reality. The rise of Trump is both a symptom of this fact and an exacerbating force.

On the other, though, this whole thing starts to feel dystopic just in terms of its structure. While it’s easy to credit the rise of streaming with the rise of “Peak TV,” as it opened up possibilities previously unforeseen, things seem to be trending in the other direction. That is, not only is Netflix trending in the direction of cancelling/ending their truly innovate shows (godspeed, Dark!), but we’re getting more and more streaming services.

It seems pretty clear that the Powers That Be want to create a new system where we sign up for a bunch of streaming services and end up paying a total that looks a lot like that old cable bill. But people aren’t going for that. Piracy went down as services like Netflix ascended this decade, but now has started to tick back up. And there are indications the number of people who pirate shows may go up significantly as there are more streaming services and more exclusive content.

But my biggest worry here is that this is all going to normalize into some capitalist logic that kills “Peak TV.” If none of them take a chance on anything, and if they all decide things on the basis of some algorithm, isn’t there every chance we end up with a bunch of mediocre dreck? And to what extent are we already?

Don’t Get Caught in Foreign Towers, or The Portrayal of Tech on TV

Also interesting is how TV shows have dealt with the rise of technology over the past decade. If we look at some older stories, for example, it seems clear that they simply would not work if the people involved had cellphones. So the technology itself can be seen as limiting some narrative possibilities. Thus we see some shows that simply pretend the tech doesn’t exist, without really explaining why, and others (such as HBO’s Watchmen) that build a world to rule them out in order to avoid the problem.

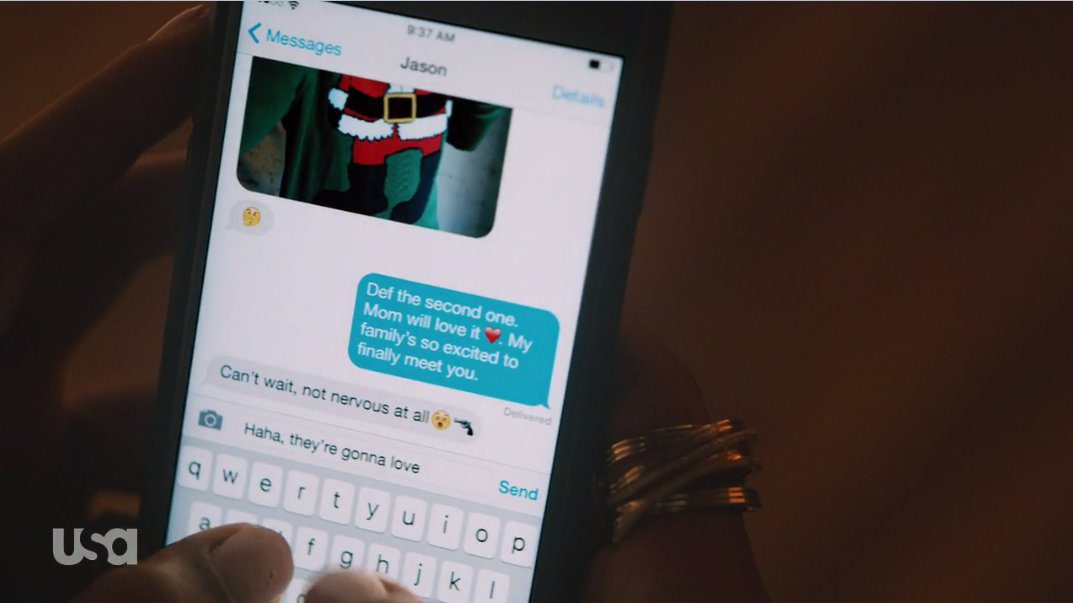

And it is a problem. How does one represent a text message, for example? We have seen various approaches, from having a bubble appear on the screen, as in House of Cards, to showing the phone itself, as in Mr. Robot. The latter approach is probably the more authentic, but also the harder to pull off in a way that fits with what one wants to do in terms of cinematography. The temptation to avoid all of this is understandable.

A similar issue arises with the depiction of social media. It’s hard to get it right. Often, the quick depiction of something “going viral” just feels off, as in Euphoria and The Politician. You get the point, but it doesn’t feel quite like how things work. And if you want to avoid the issues that would come up from using the name of an existing company, there is the further problem of what to call the thing. The Good Wife was an excellent show in a lot of ways, but Chumhum never really struck me as a convincing name.

Offer Me Alternatives and I Decline, or Are We Already Living in a Dystopic Future?

Black Mirror has generally done well with these issues, though I wouldn’t contend that it is perfect on them. However, it is the show that if you think about it could only come into existence in this past decade. Its whole premise—playing on how technology brings out the darker aspects of our souls, with the title based on both that and the “black mirror” of the phone screen—is based on the very things I have been talking about.

Some of the stories depend on technology that does not as yet exist—and would take significant and perhaps implausible leaps in the realm of neuroscience to exist—but fundamentally Black Mirror is about the world we already live in.

One could say this about any dystopic fiction: it takes elements of present day reality and projects them down the dark paths they might lead. But Black Mirror is less about where we might go and more about where we already are.

Maybe you can’t scroll back through your memories and masturbate to an old flame, but you kind of can—not just through fantasy, but through the ever-increasing database of relics the internet puts at your disposal. And perhaps we don’t have digital copies of people, but we do have the way they are inscribed in a virtual realm. What’s the line between the AI Ash we see in “Be Right Back” (who is based entirely on Ash’s internet history) and the “cookies” we see later?

We already demean one another, and treat the person online as some kind of fake—or at least some of us do.

The truth is, we are already living in the world of Black Mirror, and the best episodes of the show may well be those that recognize that. “Shut Up and Dance” or “The National Anthem,” “Hated in the Nation” and “Nosedive” equally get at elements of our society that are already here, as we’re all on social media and rating/judging people.

Those that go a step further into the realm of sci-fi, such as “White Christmas,” “Hang the DJ” and “USS Callister”, do so at the behest of getting at problems that already exist in terms of how we relate to one another in this digital age, whether it be about blocking people, online dating, or things like deepfakes.

In many ways, I feel that “15 Million Merits” is a portrait of our world. The Sisyphean bike riding stands in for the bullshit of our labor, with the idea of sudden celebrity and wealth as seemingly the only way out, although it comes with its own perils. It no longer feels like if you work hard you can make it so much as it feels like that hustle might give you a shot. Work hard to get a ticket in the lottery.

Time I Had Some Time Alone

As the 2010s come to a close, perhaps it’s a time to ask ourselves where we are going. But it’s probably too late to stem the tide. We’re going to be washed over by the streaming services, and presently. We’re going to call each other out on social media and use it to manipulate each other, because we already are doing that.

There are certainly positives, but there has been a sea change over the past 10 years that I hardly realized until I started to reflect on it. Smartphones are everywhere. Social media is pervasive. How we consume TV has changed massively, and so has the relation to how we can affect it. But although we can point to success stories about getting a beloved show uncancelled, and the whole logic of what gets renewed and what doesn’t has certainly changed, at the end of the day we’re seeing cold capitalism reassert itself.

The golden age of “prestige TV” is likely ending. Increasingly it seems that networks and streaming platforms aren’t interested in taking a risk. Netflix cancelled The OA, and I don’t think BoJack Horseman would find a home there now. Instead, they’re using our data to reverse engineer things they think we might like. And the others are largely following suit.

We’ve gotten to the point where there will almost surely continue to be really good TV out there. Some of it may be excellent, like the new Watchmen show on HBO, for example. But I think the time when outlets were willing to take a chance because they didn’t know what might hit is coming to a close.

It’s like what happened with music in the ‘90s, as we went from Nirvana to Bush to…Britney Spears. The structure is reasserting itself, even though the landscape has radically changed, and in retrospect I think we’ll view this decade as a time when artistic creativity proliferated as streaming got going and all sorts of ideas were given a chance.

There will still be excellent things that are worth watching, but I think more and more we should expect shows that are OK, or maybe even pretty good. And there is an important difference.

It can seem like there is so much good TV out there that one cannot keep up. I don’t expect that to change. What I expect to see less of is the stuff that feels exceptional: Mr. Robot, Legion, True Detective, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Bojack Horseman, The OA…Instead I expect more like The Santa Clarita Diet. (Oh wait, that was cancelled too…um…13 Reasons Why?)

We’ve been in a chaotic liminal space: between the old world that has passed away, where networks served as gatekeepers to distribution and there was a certain hegemony of the popular; and the new world where everything is dispersed and fractured on the great flat surface of the internet. Everything is available. For a moment, we might have dreamed that the Powers That Be would be unable to reign in the chaos, but we’re now seeing that they’ve figured it out. Here, as everywhere, we can see how we are almost fully into what Gilles Deleuze called a society of control.

You can have anything you want. It’s no longer about controlling what you can have; it’s about controlling what you want. It’s about taking what they know we want and giving us more of it. The important thing to see is how that is oppressive, how it shuts down the space for novelty.

So as this decade comes to a close, we should perhaps celebrate it as a time of innovation. We should perhaps celebrate that in this transitional time we even got a show like The OA at all. Because what’s coming is an apparatus that uses all of this data they have collected about us to make things they know we’ll like. Or perhaps that’s already here.