“This is but one of the legends of which the people speak…” -The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (Prologue)

In the Spring of 2003, 12 year-old me turned on his Nintendo GameCube to play The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker for the very first time. From the moment I saw the gorgeous cel-shaded title screen and heard the maritime-themed music accompanying it in all its epic glory, I suspected I was in for something special. But never could I’ve imagined how much this game would mean to me.

The feeling of wonder and adventure hit me from the start. The game’s sights and sounds immersed me in this new world begging for exploration—filled with excitement, dangers, and unforgettable experiences.

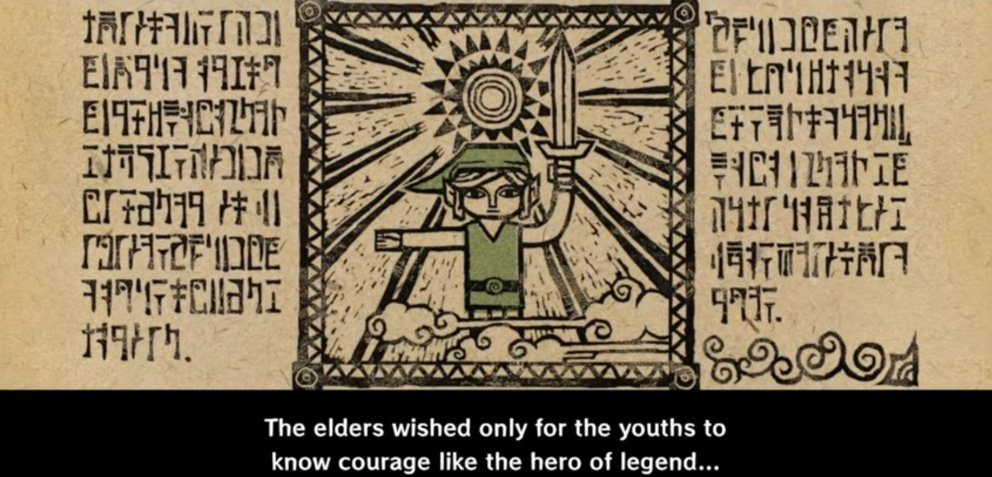

As the game starts, I was told the legend of the Hero of Time, a story passed down through generations. In Outset Island, Link’s home, it is tradition that boys receive green garbs in honor of this hero when they reach a certain age. I could feel the weight of fate on little Link’s shoulders with the knowledge that the sleepy boy living on the small, peaceful island would inevitably be thrown into something much bigger than himself—a destiny he couldn’t have possibly imagined.

Then of course, out of nowhere, tragedy strikes: a giant bird shows up and—after a short incident involving a crew of adorably quirky pirates—snatches Link’s little sister and flies away with her.

As an older brother to my only other sibling—a “little” sister (she’s 25 now) and the person I love most in the world—Link’s tiny sister being taken away by this monstrous flying creature made the stakes real for me. It was at that point when both our would-be hero and I were thrust into an epic journey, destined to become the stuff of legend.

I could write an entire book on how amazing I think this game is and how much a part of my life it became. Almost twelve years later, when I joined the U.S. Navy and spent months at a time out to sea, every now and then I would step out into the fantail, look out from the hangar bay, or stand on the flight deck of the aircraft carrier I was assigned to. I’d take in the sight of the endless sea, feel the ocean wind on my face and breathe the salty air while humming to myself the Great Sea theme—the epic song that plays as Link sails the vast oceans aboard the King of Red Lions. Needless to say, asking my parents all those years ago to buy me this game was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.

But now I wonder if it was, in fact, my decision. Did I ever really have a choice?

Would it have been possible for me not to have this experience at all? What if I had skipped The Wind Waker or chosen a different game to play? After all, I hadn’t even played the series that much in the past and I only ever tried this specific entry out of random curiosity. What if I had picked up sports as a young boy instead and never gotten into video games? I don’t remember the exact circumstances that led to me playing the game all those years ago, but now I wonder if there’s more to it than I thought.

Could there have been a different version of events, one in which I never chose to play The Wind Waker? Or were things as they actually happened a product of something else—a predetermined causal chain of events and reactions, cause and effect, destiny, or fate?

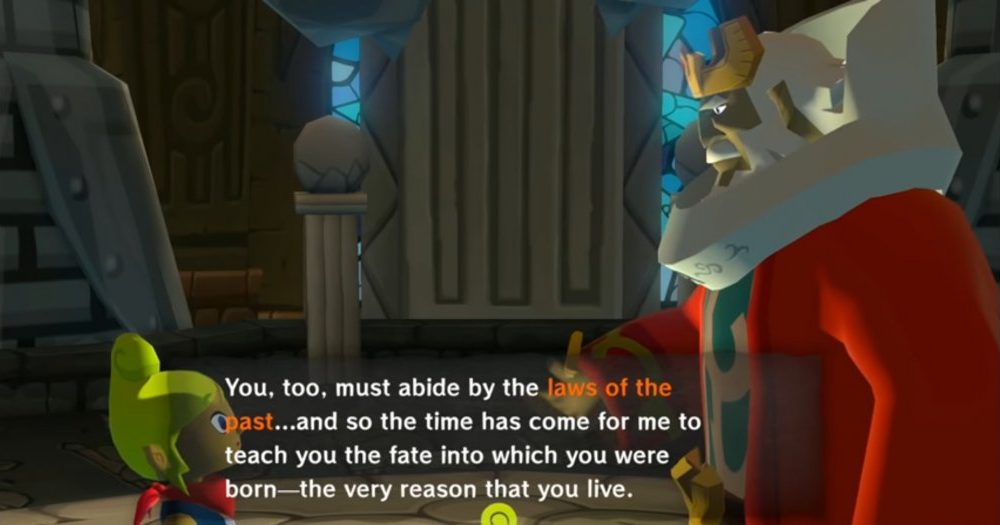

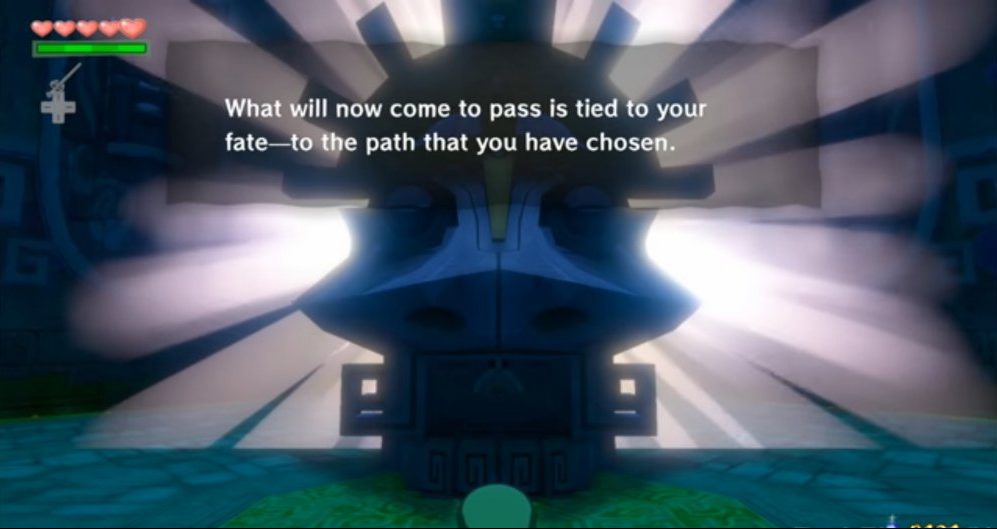

The Hero of Winds, the version of Link I played as in the game, seems to have been destined to become so according to in-game lore. In fact, it is implied in one way or another that all the Links throughout every game in the series—and the different incarnations of Zelda and Ganon—are as well. The main characters in The Legend of Zelda are often instruments of fate, destined to become who they have to become: heroes, sages, princesses, and villains.

But this is a fantasy story in a video game. Clearly my life—real life—doesn’t work that way. The universe is chaotic, ruled by entropy. And when it comes to the decisions I make as a human being, I do whatever I choose to do. I have the power to shape the course of my life through my choices and actions. I make my own fate. I have free will.

Right?

Well, it turns out that it might not entirely work the way I think it does.

In the realm of philosophy, free will is the belief that some human actions are freely chosen in a metaphysical sense. This would account for my feelings of having a choice whenever I make a decision—such as when I decided to convince my parents to shell out the 50-something bucks The Wind Waker cost way back when.

Hard determinism, on the other hand, argues something different: that all events, physical or otherwise, are caused by past events such that nothing other than what does occur could occur. In other words, due to cause and effect, everything that happens—including my choices—are a product determined by previous events. Free will, therefore, is just an illusion of personal choice.

Using The Wind Waker as an example:

If free will is true, Link decides to set out on his quest when confronted with the choice because he freely chooses to do so. He acts courageously of his own volition and eventually becomes the hero he ends up being. In theory, all other factors being the same, he could’ve very well chosen something else.

Instead, if hard determinism is in fact how things work, Link’s journey and his decision to set out on it are just a product of all the previous, relevant factors that influenced the event—both external and internal. He acts as he does only because it was predetermined by these factors to happen. Even if he thinks he’s making a choice on the matter, in reality, he can’t possibly do anything other than what he ends up doing. It’s all just meant to be.

So down the rabbit hole I go.

Traditionally, an action can be defined as “free” only if the person or agent making the decision could have done something else. Hard determinism, from its part, allows no space for options.

The deterministic concept of causation is the idea that events, like the Master Sword being pulled from its pedestal, are always the product of a previous event—in this example, the pulling force applied by an adorable, green-clad hero. Every event is only the product of a cause, which in turn determines said event. This also would apply to human experience and choices. As far as this reasoning is concerned, no one is ever really free to choose anything.

Agent causation, however, presents the notion that a being with a mind of its own can, in theory, start an entire chain of causality that wasn’t caused by anything else that came before. In this case, the Master Sword was pulled from its pedestal not simply due to a pulling force exerted on it, but due to Link choosing to pull the sword—therefore acting as the real cause of the event. Had he chosen otherwise—and according to this, he could’ve—the legendary blade of evil’s bane would’ve just stayed where it was.

That being said, what would cause Link to choose to retrieve the Master Sword in the first place? By the end of The Wind Waker, Link had used the Master Sword to defeat Ganondorf and save the day like many other heroes had done in the past. But none of it would’ve happened without something having happened before that led to it.

Let’s explore this.

Link defeats Ganondorf. He defeats him using the Master Sword, which he has in his possession because he pulled it from its resting place and restored its power. He did this during the journey he set out on after his sister got taken away by a bird, which was itself sent by Ganondorf to steal away girls with long ears apparently in an attempt to capture Zelda (a girl with long ears) in the first place. Tracing the events back in this manner implies that Ganondorf was ultimately defeated, ironically, only as a result of having attempted his evil plan in the first place.

Even if Link had actually made the choice to do all of this genuinely, instead of cowering from the start and leaving things to run their course for example, the argument can be made that things would’ve ultimately turned out the way they did because it was the only possible way they could. Agent causation would argue that Link made his own choices and created causal chains along the way, but wouldn’t these choices have been a result of other particular causes?

The reason Link chose the way he did could’ve been due to his own beliefs, desires or temperament—things that would’ve essentially been beyond his control and would’ve also come before the choices were made.

Maybe the fact that he was raised on an island that valued the courage displayed by the Hero of Time—as implied by their tradition of dressing boys in the green of fields when they came of age—had an influence on his beliefs. Maybe his desire to save his sister served as a driving force, compelling him to face his potential fears and find the inner strength to do what was necessary. Maybe his own personality traits: willpower, determination and courage—played a part in keeping him steadfast on his quest until he accomplished the mission he set out to do. Maybe all of these things—as well as countless other internal and external factors—in a way, served as causes that “forced” him to do as he did.

This could apply to pretty much anything. From big decisions with significant weight, like saving an ancient land from a rising tyrant; to seemingly irrelevant ones, like getting good grades to convince my dad to pre-order a certain video game. It certainly seems to make sense.

But what does this mean in terms of life choices? What about morals? What about assigning praise or blame for individual actions?

Hard determinism seems to check all the boxes when it comes to our understanding of our physical world and the events that take place within it (although recent quantum science discoveries might beg to differ). But in that case, are people actually responsible for the things that end up happening in their lives?

If things are just predetermined, can I really value Link’s courage and determination? Is he the hero he seems to be at face value? After all, if he had no choice but to do the things he did, maybe he’s not that much of a hero.

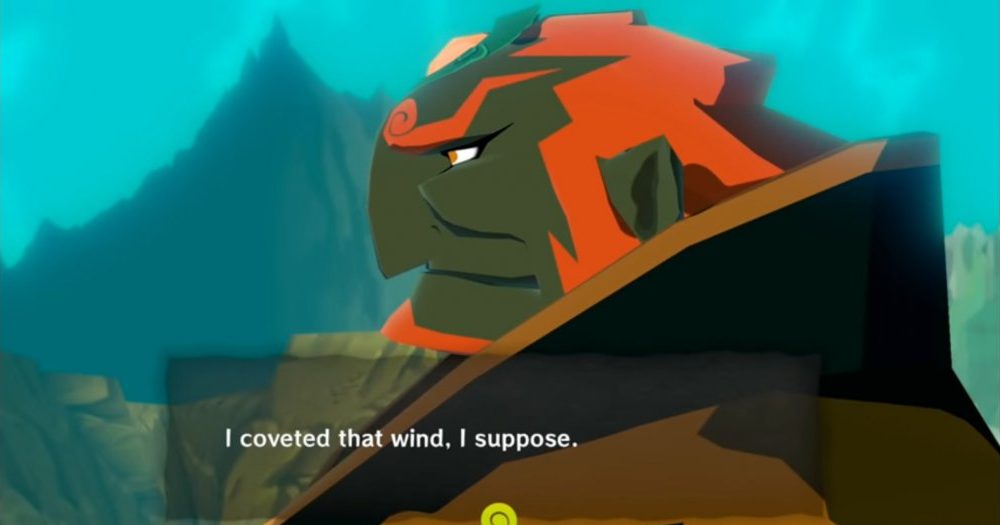

What about Ganondorf? If the same applies, is he really to blame for his evildoing, or was he cursed by some metaphysical causal chain of fate, becoming essentially a victim of the same forces that raised Link to hero status?

And what about me? Do I really have a say in the things that I do, in the decisions I make? Should I be proud of my moral decisions and accomplishments? Should I blame myself for my morally reprehensible actions, mistakes, or failures?

My chances of coming up with a conclusive answer seem far-fetched at best. At worst, they’re probably futile. Logic seems to point to a deterministic view as the rational alternative, but then there’s the feeling we all seem to share that our choices are our own—that we can analyze factors, predict possible outcomes, consider our personal values, and decide accordingly. Should I dismiss all of this, or are the arguments for free will still worth some extra consideration?

Philosophers apparently have debated on this for a really long time, and alternatives based on compatible views—where certain parts of both sides of the argument may be able to exist together—have also been explored, I guess, to try to find a satisfying middle ground.

Free will or not, the fact of the matter is that Link does end up saving his little sister and defeating the villain. And I did, in fact, end up playing The Wind Waker as a kid and looking back at my experience with the game years later as I sailed the seas aboard a Navy ship.

I have made tons of decisions throughout my life. Some I’m proud of, some I regret. One day, when I’m old and gray (if I make it), I might look back and relish the fact that I chose right more times than not, or maybe I’ll lament the fact that I didn’t.

I might be able to take pride in the knowledge that I exercised my free will, made my own fate, and shaped the course of my life through my actions and choices—for better or worse.

Or maybe I’ll realize that whatever ended up happening was much like one of those legends of which the people speak…

…And at the end, it was all just meant to be.

Good article. I had a great time reading it. I can’t wait to see your take on Bioshock and Bioshock:Infinite.

I love every single article of yours, but this one hits different. “The wind waker” is certainly one of the greatest games I’ve ever played!

Loved this article! Wind Waker is still my favorite game of all time.