Leighton Evans and Paul Billington co-wrote this, but we can only credit one writer. If you like it, credit both in your mind. If not, it’s all Leighton’s doing and feel free to post angry comments at the end.

Star Trek: Picard is coming and excitement has been building amongst fans ever since Sir Pat Stew (it’s Star Trek—we’re all family here!) took to the stage and announced it last year. With Discovery finally finding its feet this past year, it appeared that there was no way we were ever going backwards—to Enterprise, Deep Space Nine, Voyager or The Next Generation. Their stories have been told, the lost have come home and—oh yeah—Sisko was a God (and not just because he was a good cook). Things had been wrapped up. It’s been the slick JJ Abrams universe since those days which, for many, has not quite captured the essence of what Star Trek really has been all about.

Which is?

Well, we’re here to tell you what that is (or what we believe it is) by taking a look at the person who many folks believe is the best of all captains, and a character that we believe encompasses all the Great Bird’s (Gene Roddenberry, original creator of the show) optimism for what we, as humans, could be—and therefore the very essence of Star Trek…hopes, ideas and beliefs—distilled by great writers and producers into one person: the great Captain Jean-Luc Picard.

“Captain Picard is the hero we need right now. He exemplifies in some ways even more than James Kirk—and I’m not gonna get into the Kirk vs Picard argument because I love Captain Kirk, he was my first captain—but Picard is even more of an exemplar of everything that is best about Star Trek’s vision for the future…”

OK, it looks like one of the new showrunners (Michael Chabon) agrees with us here. So what is it that makes Picard a man who seemingly hits all the right notes for both the audience and the people seeking to entertain us?

No one can really deny that early on in ST: TNG (Star Trek: The Next Generation), the new Captain was initially not so easy to relate to. Initially gruff, humourless, inanimate, pontificating…The pilot “Encounter At Farpoint” did little to ingratiate the lead of the show to an audience used to Kirk’s occasionally frivolous exploits, Spock and Bones’ comedic banter and the oft-times heavy-handed planet of the (Nazis…Gods…kids with psychic powers—fill in the blanks): and the blunt lesson to be delivered/antagonist to be overcome, in the latest episode.

However, the world had changed dramatically between the cancellation of TOS (The Original Series) and TNG’s pilot. We only need to look at changes in human rights to prove this: we saw the racial and also sex discrimination acts in 1965; in 1976, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); in 1967 America saw the Detroit Riots; in 1968 the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.; in 1979, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW); in 1984, the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; and in 1989, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, etc.

These changes to human and civil rights are connected to the fundamental changes in character traits between Star Trek’s first and second captains. Did it affect what the show was able to explore? Absolutely. In new and evocative ways. Whilst drama explores the human condition, science fiction allows itself to predict and to fantasize…so as Kirk was the combination of American ideals in the 1960s, Picard was the combination of Western ideals in the 1980s. We certainly move away from TOS’s (jock) traits into a more reserved and thoughtful Captain, one created after Vietnam and the closing of the Cold War (the new relations between humanity and Klingons also being a clear nod to this new era). The world was ready to move on from the brink of war, to explore the external and internal possibilities of being alive, of moving forward with renewed optimism, armed with the lessons learned from our mistakes (though admittedly, a cynicism that remained in the 20th Century, was not visible by the 23rd—we’d moved on even more). Star Trek was a beacon to this change, and the stage was set for Captain Jean-Luc Picard.

We love the opening shot, floating toward Picard’s (assumed) ready room—he’s pitched in shadow only to step out, face half-cast in light. A confident grin, barely visible under his intense brow and piercing eyes and all the time hearing his stardate voice-over. For us, the shot embodies the lust for exploration, to move out of the shadows. We get what he is, just as we get what the show is. It’s going to be a trek across the stars. We can see the clean-cut face, the pressed new uniform (uh oh—he’s wearing red…that doesn’t bode well if you are a fan of TOS).

But that’s not all. This shot could also be representative of Picard as a whole: someone who holds something of himself back, at least while wearing the uniform. He’s a captain after all—the presentation of someone in charge, to be looked up to, to be respected—they are all a part of the makeup of the man. As the series continues, the writers will gradually acknowledge the man behind the uniform—and it’s these two pieces of the puzzle that give us Star Trek’s unique vision of the future and the character that many found captivating and inspirational.

Picard as a man in charge of a starship could simply have worked because Sir Patrick Stewart, Shakespearean thespian, commands his stage with gravitas and that rich, baritone vocal delivery that doesn’t require well-scripted dialogue to get our attention. The fact that he does get great lines, sometimes verging on a soliloquy or two (if you will), only adds to the quiet competence and confidence that exudes from him. There is no shortage of episodes that demonstrate him as an intelligent, thoughtful, astute and perceptive officer. In fact, it’s the idea that he isn’t overwhelmingly.. well…full of himself, that finally endears him to us. Take the late Season 2 episode, “Q Who?”—our first proper look at an adversary far beyond any the show had seen so far, and one that proved interesting enough to survive into other spin-offs—the Borg. Judging the crew to be far too self-confident in their supposed ability to deal with ‘what’s out there’, super-being Q decides to subject them to a terrifying encounter that leaves 17 crew dead and Picard admitting something that, in Kirk’s era, would likely have been thrown out of the writers’ room:

Picard—“You wanted to frighten us. We’re frightened. You wanted to show us we were inadequate. For the moment, I grant that. You wanted me to say ‘I need you.’? I NEED you!”

Q—“That was a difficult admission. Another man would have been humiliated to say those words. Another man would have rather died than ask for help.”

But this man is Jean-Luc Picard. He’s not oblivious to the reality of the situation. He’s not so proud as to keep his crew in danger, to blindly assume that it could be a matter of firepower and gumption that will win the day. He’s considered his options. He’s consulted his command team, and he’s talked with Guinan—the one person who has encountered the Borg before. Will he look weak in front of Q? Maybe. Will his admission, his acknowledgement of limitation and fear, fall on deaf ears? Possibly. Will his crew think that he hasn’t protected them, hasn’t weighed up the consequences of his actions, hasn’t acted like a true leader? No, they will not—not just because he’s the captain, and that’s just how it is. He will ponder his choices, seek lessons in the ramifications and grieve the losses the Enterprise has suffered.

It’s not the last time that he will demonstrate these skills when things get arduous, when the decisions are challenging and when his principles—or even the foundations of their 23rd century way of life—are being perverted, undermined and threatened. Yes, the hope for the future is bright, the cultural advancements tangible, and the Federation has advanced to become a unifying construct in the galaxy. But all is not perfect.

The human condition, arguably the fate in which our flaws will always pursue our determination toward greatness, has not quite achieved Rodenberry’s vision. Data, being the perfect hook on which to explore this topic, has provided us with some of the most complex arguments which not only show how Picard grapples with complex and delicate situations but also his motives behind his decisions and how he stands by them.

“The Measure of a Man”, an episode that Sir Pat agreed with fans was ‘the first truly great episode of the series’ has Picard flex all of his strengths in a courtroom over Data’s right to decline an order which would most likely kill him. However, even before they reach the courtroom Picard supports Data’s decision in not handing his brain over to Starfleet for research, and when ordered to do so, it is Picard (although not his own idea), who suggests to Data that he resign his commission.

At first, we could be lured into the belief that Picard is abandoning Starfleet regulations over friendship, but as the episode progresses we discover that he is the pinnacle of what Starfleet is intended to be and that it is those who wish to harm Data who have strayed from the path. When faced with the fact that Starfleet has failed both Data and itself, Picard stands without thought between them, telling Data to resign.

Unfortunately, the gambit fails. Starfleet initiates legal proceedings to prove Data is Starfleet property and unable to resign because they refuse to see Data anymore than a machine. They even accuse Picard of humanising the android because he ‘looks human’. What follows is pure gold, revealing the captain’s negotiating prowess as he articulates his argument. Even in his opening statement, you can see how he understands that Data is more of the some of his parts:

“We are also machines, just machines of a different type. Children are created from the building blocks of our DNA but does this make them our property.”

He continues to use reason in his debate until the prosecution (Riker) showboats by turning Data off. All is deemed to be lost. However, Picard once again shows us that it’s alright not to know everything and is comfortable in asking for help. This time speaking with Guinan, who gives him an outlook on robotics and possible slavery. When he returns to the courtroom, it isn’t to argue that Data isn’t property or that he’s more than a machine. That argument was lost when Riker flipped Data’s switch. No, he returns and twists the light on us, Starfleet, and what we (the audience) want to be. Roddenberry’s vision. How do we want to be judged? Can we be better than we are? It’s not what Data is, but what he can become and it is also about what we become should we de-humanise those we do not understand.

Picard’s loyalty to Data can be used as possibly the best example of his loyalty to all his crew and his unwavering belief in Federation’s ideals. They are both paramount in this episode as with many more, including putting him with odds against Starfleet a number of times. The episodes “The Measure of a Man”, “Drumhead” and “The Offspring” all depict his core principles in equal rights, and all of them show his resolve. If the show had been in the time of Netflix, we are sure we wouldn’t have had any cracks in continuity. Which is why we like to think that in 1990, Jean-Luc Picard, as with all the characters in the serialised show, had to develop within the context of the episode as well as over the course of the entire series. But lines and episodes like these stick with us:

“There are times, Sir, when men of good conscience cannot blindly follow orders. You acknowledge their sentience but ignore their personal liberties and freedom. Order a man to turn his child over to the state? Not while I am his Captain.”

Jean-Luc isn’t perfect, however. In “The Offspring”, before he eventually throws himself between Data and child-catcher General Haftel, he reprimands Data for not consulting him before constructing his offspring, Lal. As people who have recently watched these episodes in close succession, are we to understand that Picard forgot his own argument in that we are also machines? Okay, sometimes continuity isn’t paramount (more later). Even after Data argues that Picard doesn’t require anyone else on board to consult him before they…*cough* procreate…Jean-Luc confronts Haftel, explaining that it is hard for them to understand, but to Data, Lal is his daughter. As such we get to see that Picard, once convinced by another’s argument, will fight their right to hold such a view.

The lack of serialisation we mentioned, the need for episodes to be self-contained (one of the earmarks of syndication back then) was hampering to TNG and to the characters a lot of the time—that reset button effect. However, one episode in particular, dared to push that boundary a little. “The Best of Both Worlds” two-parter is seen by many to be the pinnacle of what TNG could offer—a cliffhanger no one saw coming, with Picard’s life in the balance and the stakes (the assimilation of humanity) as high as they could be. However, this is a key episode for Riker, not actually Picard. It’s Riker’s decisions, his future, his abilities that are in question.

In actuality, it’s the effects of this episode that give us the much-needed human insight into Picard—and that’s explored in the next episode, “Family”. As Jean-Luc explains to Counsellor Troi, “what better place to find oneself than on the streets of one’s home village.”

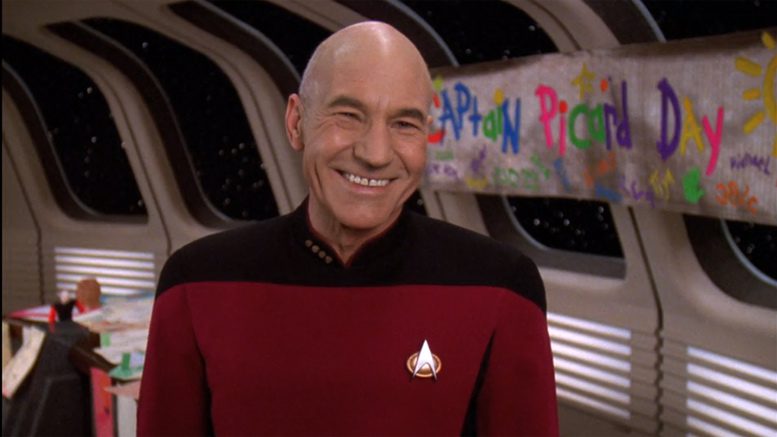

Following his rescue and disconnection from the Borg hive mind, the Enterprise returns home to Earth, and Picard to France, where his brother, sister-in-law and nephew reside at his family’s vineyard. Picard’s sense of humour, which is seen more and more as the series develops and the character overlaps with the actor portraying him, is on display when he greets his nephew as his uncle, and the other greets him as his nephew (Picard’s humour tends to be quite dry—witness his joke to Riker about holding a ‘Commander Riker’ Day and submitting an entry himself, in “The Pegasus”).

Jean-Luc seems both tense and relaxed—relaxed at being away from the Enterprise after his ordeal, terra firma beneath his feet, but tense at returning to a judgemental brother Robert, who fails to see the allure of space travel and dismisses Picard as the ‘golden child’ of the family, a boy/man who could do no wrong. This historic resentment will show us shades of Picard’s character we have not seen before, and prove to be a catalyst for dealing with the horror of being intellectually, physically and emotionally ‘raped’ by the Borg.

Picard is human. Despite initial criticisms of the captain as a distant, almost-Vulcan like intellectual that the audience couldn’t accept after the passionate heroics of Captain Kirk, the show has given us a true leader—a man of conviction and compassion, of integrity and rationality, almost unshakeable in the command of his ship, of any given situation, of his own faculties…but a man of self-doubt?

As Picard questions his future above the skies, his brother brings him down to earth. As sometimes only family can, he pokes at Picard’s perfectionist drive and breaks through his defences in a way only the Borg ever have—and the effect is devastating. The terror of his capture and assimilation and the realisation that he is fallible and has failed to live up to his own incredibly high standards gives us all pause. We too are not always strong. We stumble. We can be hurt. We are “terribly hard on [ourselves]” as Robert Picard puts it when comforting his brother. How we choose to respond to hardships, to accept our limitations and to still keep going…well, that’s not just the message Picard receives, but also the ethos of Star Trek itself—that we will continue to grow, and stumble, but always to keep moving, keep striving.

As the show moves into its later seasons, we found the smaller, less obvious episodes were ones that added to the overall picture of the man behind the uniform. “The Inner Light” and the two-part “Chain of Command” (all incredible episodes with powerhouse performances) lacked another episode afterwards that would have examined the repercussions of the events therein. Both of these episodes would perhaps have benefited from a continuation later in the series—the characters certainly would have. We would have loved to see the effects of Picard living an entire life previously or dealing with post-traumatic stress from the hands of David Warner. The show wasn’t quite there yet…maybe if it had been produced after Deep Space Nine or *cough* Babylon 5…

Instead, there were smaller, fewer ‘showy’ episodes that gave insight and tones to the character previously unseen or hinted at. Take “Attached”, where Dr Crusher and Captain Picard share the thoughts of one another via brain implants. The main plot is almost secondary to the tiny revelations that come from each hearing the private thinking of other.

Picard: [checking the map] “This way.”

Crusher: “You don’t really know, do you?”

Picard: “What?”

Crusher: “I mean, you’re acting like you know exactly which way to go, but you’re only guessing. Do you do this all the time?”

Picard: “No, but there…are times when it is necessary for a captain to give the appearance of confidence.”

The Captain has always given that appearance but to hear him admit that there are times it is merely guesswork at play endears him to us. As does his admission of feelings towards Dr Crusher—feelings that, by the end of the episode, do not appear to be reciprocated. Again we can relate, and admire him for his confession despite the disappointment when Beverly chooses not to continue the conversation at the end of the episode.

We’ve mentioned Beverly and his feelings for her, perhaps the reason for her not continuing the conversation is while she learned a lot of who Jean-Luc is in the episode, she already knew what she needed to know about him all the way back in the beginning. She explains to Wesley that she certainly isn’t afraid of him and that “Great explorers are often lonely, no chance to have a family”. She is, of course, correct, Picard is a great explorer and his passion is revealed throughout. Not just the Captain of the Enterprise, but every interest he has outside of the chair reveals something of why he sits in the chair. The freedom of horse riding, the precision of fencing, archaeology and understanding alien cultures—even his love of Shakespeare displays his commitment to exploration of the human condition.

And at this point, perhaps we discover an unexpected reason that Picard as a character is one of the best Star Trek has to offer. All the positive traits we have mentioned, from dedication to ideals through to friendship, from clear thinking through to a dry sense of humour—and everything in between (and it’s rude not to mention that he has a good right-hook—witness the taking down of a terrorist on the bridge during the episode “The High Ground”).

The other element is that, whilst we cannot relate to being the Captain of a starship somewhere in the faraway future, we can relate to someone who experiences unrequited love. We ourselves can harbour warmth and compassion but wear a public face that hides those things which could be seen as weaknesses. We can see ourselves in someone who is fallible, in someone who does not always win. “It is possible to commit no mistakes and still lose. That is not weakness, that is life.” Well said Jean-Luc, well said.

And so a new series set years after Star Trek: The Next Generation is almost upon us. When asked if Picard is a version of himself, Patrick Stewart replied “I profoundly respect his views on life, his attitude to freedom of expression, to democracy…There came a point, maybe sometime in the third season, when I realised that the gap between Jean-Luc Picard and Patrick Stewart had gotten narrower and narrower.” And for many of us, it was around the third season that the overall quality of The Next Generation was seen as a turning point, moving from under the shadow of TOS. Perhaps because we got to see more of the human being that inhabited the captain’s uniform. Perhaps because the messages, ideology—the spirit of Star Trek —lived in Patrick Stewart as much as Jean-Luc Picard.

On that note, we will let the actor himself have the last words…

“Well, as our world goes one step forward and two steps back, I think there is much of the man [in the new show Star Trek: Picard] that we certainly knew in Next Generation. His modesty, his patience, his affection—no, affection is too weak a word, his passion for humankind and for the future of the solar system that we inhabited…one of the great things about Jean[-Luc] was he was a great listener and would only speak when he felt everyone had expressed what they believed. The crew of the Enterprise came to know that they were at liberty to speak the truth about what they believed and what they thought.” Sir Patrick Stewart.