PopCulture25YL looks back at the music and shows from the month that was January of 1995 to explore why they’re still relevant to us 25 years later. This week brings us the last episodes of Liquid Television, WWF Royal Rumble 1995, and Leftfield’s album Leftism.

VHS In The VCR

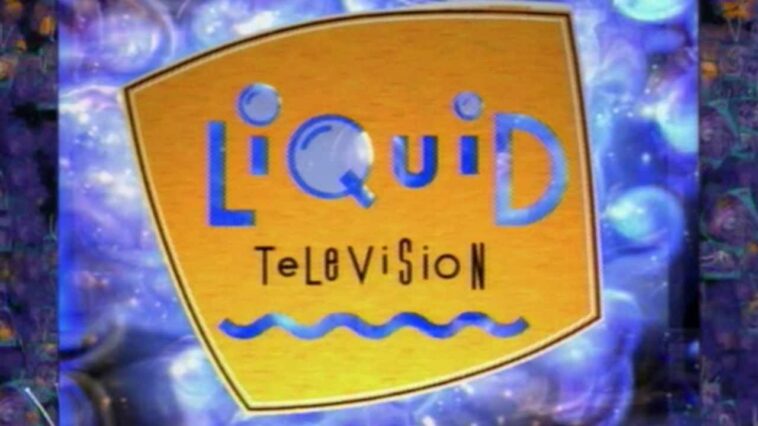

Liquid Television by Rob King

Liquid Television ran for three seasons from 1991 to 1995 on MTV. It heralded Avant-guard American adult animation at a time when The Simpsons (1989-present) had only recently picked up the torch from the last syndicated adult sitcom in memory, The Flintstones (1960-1966). Ren and Stimpy (1991-1995) was testing the waters of Nickelodeon’s evening audiences alongside Liquid Television, but MTV was looking for a different demographic. Liquid Television was bringing their Avant-guard sensibility cut with the lowest-brow of postmodernism to the last bastion of Generation X. Notably, Ren and Stimpy’s John Kricfalusi was solidly rooted in the classical schools of Filmation and the Ralph Bakshi schools of animation, whereas Matt Groening earned his chops cartooning for Wet: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing and animation for The Tracy Ullman Show. Wet was a magazine that incorporated innovative graphic art stylings to portray cultural issues imaginatively, and there was inevitable overlap with the new wave underground comix movement as seen in Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s Raw comix; they shared talent. In the summer of 1991, MTV’s Liquid Television was being billed as “an animated variety show,”[1] and while that sold well in the television ‘zines, MTV creatives were allowing a more unique show that looked to the talent of this comix movement and post-modern literature. It is well-documented that David Lynch said his inspiration for directing his earliest short films came from an experience where he saw them as moving paintings. If we can separate that notion from general movie or television production, we could then begin to see Liquid Television as an anthology of moving new wave commix, comix literally animated.

The first season of Liquid Television boasted the talents as seen in “Stick Figure Theater” shorts, Bill Plympton shorts, Peter Chung’s Aeon Flux, and the serialized Winer Steele. Season 2 doubled down on talent from Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s Raw comix introducing Mark Beyer’s “The Adventures of Thomas and Nardo” and Charles Burns’s “Dog Boy” cited in an early article as “Raw Dog.”[2] Aeon Flux returned, and the world was introduced to the cartons of Mike Judge with Office Space and Beavis and Butthead. In its final season, Season 3, most of the notable titles above were gone. “Stick Figure Theater” would continue to run the course of the series, and the notable additions were “Crazy Daisy Ed,” “Brad Dharma: Psychic Detective,” and “The Blockheads.” Aeon Flux and Beavis and Butthead would go on to their own highly popular series, but those who caught Liquid Television late at night, changing the channel over from TNT’s MonsterVision or USA Network’s Silk Stockings or simply awaiting the Headbanger’s Ball with Matt Pinfield would probably remember the more obscure shorts in their memories. Those obscure shorts borrowed heavily from Raw as can be seen in comparison illustrations included.[3] Another famous short is titled “Human Bomb,” which is narrated by Mark Leyner, who was making a reputation on college campuses with his short story collection My Cousin, My Gastroenterologist. “Human Bomb” was adapted from his story “i was an infinitely hot and dense dot.” Ultimately, Liquid Television confused critics but remains uniquely its own, and while we now have Adult Swim and innumerable adult cartoons spun out of Jananimation, no following animated series has been successful in imitating the plotless inventiveness of the anthology series.

[1] Solomon, C. (1991, Jun 01). MTV’s ‘Liquid’ A Cut Above Saturday Cartoons. Los Angeles Times (1923-1995) Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.lib-e2.lib.ttu.edu/docview/1638629694?accountid=7098

[2] Rhea, M. (1992, 10). Animation Highlights Television Production. American Cinematographer, 73, 14-21. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.lib-e2.lib.ttu.edu/docview/196322231?accountid=7098

[3] Kelly, M. (2008, Spring). Art Spiegelman and His Circle: New York City Comix and the Downtown Scene. International Journal of Comic Art, 10, 313-339.

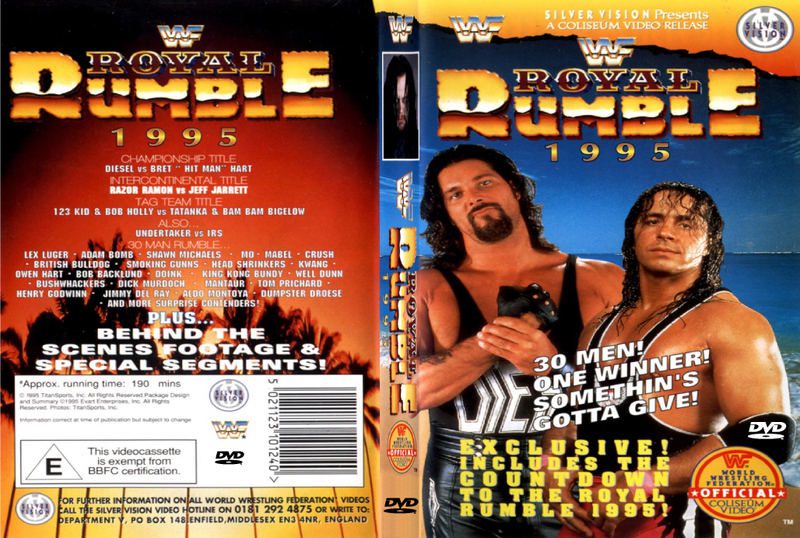

WWF Royal Rumble 1995 by Chris Flackett

25 years ago, on 22nd January 1995, the WWF presented arguably their second most important event of the wrestling year (with the winner of the Rumble traditionally getting the main even slot at Wrestlemania, although not so generally with the early Rumbles).

It’s an interesting event in hindsight. 1995 saw the WWF have a poor year in terms of product, the superstars of yesteryear having moved on (to WCW in a lot of cases) and quality replacements—outside of Bret Hart, Shawn Michaels , Diesel and Razor Ramon—were had to come by. This was the year of awful gimmicks like Bob “Spark Plug” Holly (a racing driver) and Mantaur (well…you figure it out). Vince’s obsession with monsters (any big, imposing men, regardless of talent) led to jobbers like Mabel headlining major Pay-Per-Views, to mass apathy and a major drop in profit. There was a period of time, in fact, at least for a couple of years, where the WWF were dancing on the edge of collapse. The Attitude era would save the company but before then we had this, “The New Generation,” to contend with.

The worst of the worst is The Undertaker, back when he was a better gimmick than wrestler, sleepwalking through a stallfest with everyone’s favourite taxman(!) gimmick, IRS. That the match led to King Kong Bundy stealing Undi’s urn, setting up a Wrestlemania match between the two, is just sour icing on an already burnt cake.

Razor Ramon’s intercontinental title loss to Jeff Jarrett showed a commitment at least to building new stars, even if interference runner The Roadie (later Road Dogg) drew more heel heat than Jarrett did.

New WWF champion Diesel took on former two time champion Bret “The Hitman” Hart in the best match of the night. Part of the failure of Diesel’s reign is that he often had poor opponents that failed to elevate him. You are only as good a babyface champion as your heel opponents, to paraphrase Adrian Street. It also didn’t help that while Diesel’s face turn at the end of 1994 got him over with the fans, he lost the edge that had piqued their interest in the first place (see also: Roman Reigns). Being forced to utter banal babyface platitudes did Diesel no favours.

Thank God for Bret. He always had great chemistry with Diesel, and while this is not their finest hour, due to an overbooking of interference that leads to a no contest, it is still a compelling contest that demands another look.

The Rumble match itself is memorable for being the only Rumble to have 60 second intervals between entrants, leading to an over-quick match that only highlighted the lack of depth on the roster at the time. Hell, they brought back Dick Murdoch for God’s sake! The lack of big superstars hurt any excitement there might have been and the 60 seconds idea was scrapped for future Rumbles.

The eventual winner though, Shawn Michaels, was the right call on the day. He entered at number one and hung on until the end with number two entrant the British Bulldog, “skinning the cat” to avoid elimination by mere inches of space between foot and floor and taking Bulldog by surprise to eliminate him and claim his spot in the main event of Wrestlemania. This was a big moment for Michaels, starting the wheels moving towards his face turn and becoming the face of the company the following year.

In the meantime, the Rumble exposed a classic Vince tactic, one he uses often but was more noticeable here due to the poor roster. Celebrity involvement. Pamela Anderson, hot on the heels of her success in Baywatch, engaged in some “titillating” skits (changing behind a screen whilst interviewer Todd Pettengill laughed nervously, anyone? Jesus…) but otherwise looked awkward and like she’d rather be anywhere else. There to promote that she’d walk the winner of the Rumble to the ring at Wrestlemania, she added nothing of value to proceedings at all.

Laurence Taylor on the other hand…

A legendary footballer, he was by no means the first celebrity to involve him physically in a wrestling match or angle, but in his pull-apart confrontation with Bam Bam Bigelow, furious at having lost his match and lashing out at Taylor, it led to the first celebrity to ever wrestle in a singles main event headliner at a Wrestlemania. It was big news at the time and was repeated later in WCW with varying results.

Strong disagree on this

“The ’90s brought alternative music of all styles together. It was great for us teens as clubbing covered every genre. Skaters, goths, punks, indie kids and ravers were all friends and had a real sense of community and enjoyment of everything that came within the culture together.”

There was some crossover, sure, but one of my abiding memories of the early 90s is of a huge rift between ravers and grunge kids. The former often felt that electronic music wasn’t “real music”, the latter that “real music” was an outmoded and conservative concept.

Also, I’d argue that Leftism was more *of the moment* than seminal. 1995 was the era of trip hop and Solid Steel. Eclecticism was becoming the order of the day in a bunch of well-regarded club nights, like James Lavelle’s That’s How It Is and Cold Cut’s Stealth, not to mention whatever that club was that ran at the original Concorde in Brighton. You would hear gabba mixed with hip hop mixed with house mixed with techno. Fucking hell, I wish I could remember its name, it rocked…

Opinions, I’ve got ’em!

Strong disagree on this

“The ’90s brought alternative music of all styles together. It was great for us teens as clubbing covered every genre. Skaters, goths, punks, indie kids and ravers were all friends and had a real sense of community and enjoyment of everything that came within the culture together.”

There was some crossover, sure, but one of my abiding memories of the early 90s is of a huge rift between ravers and grunge kids. The former often felt that electronic music wasn’t “real music”, the latter that “real music” was an outmoded and conservative concept.

Also, I’d argue that Leftism was more *of the moment* than seminal. 1995 was the era of trip hop and Solid Steel. Eclecticism was becoming the order of the day in a bunch of well-regarded club nights, like James Lavelle’s That’s How It Is and Cold Cut’s Stealth, not to mention whatever that club was that ran at the original Concorde in Brighton. You would hear gabba mixed with hip hop mixed with house mixed with techno. Fucking hell, I wish I could remember its name, it rocked…

Opinions, I’ve got ’em!