The Simpsons was undoubtedly one of the best shows on television for its first nine seasons, but for me, Season 8 always stood out as being truly exceptional. It contains, in my opinion, 11 of the best episodes of all time (“You Only Move Twice,” “Bart After Dark,” “Lisa’s Date with Density,” “Hurricane Neddy,” “El Viaje Misterioso De Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyage of Homer),” “The Springfield Files,” “Homer’s Phobia,” “Brother from Another Series,” “Grade School Confidential,” “In Marge We Trust,” and “Homer’s Enemy”), as well as about 13 other solidly great episodes. While the early seasons are all pretty fantastic, and each contains a couple of episodes that are absolute gems, Season 8 just hits it out of the park over and over again.

The season includes some of the most often-quoted jokes (“I saw one of the babies and the baby looked at me!”), most ingenious concepts (Homer obliviously working for a supervillain), and most poignant emotional journeys (Skinner and Krabappel finding love, only to be forced to choose between their relationship and their jobs) in the history of The Simpsons. This is the season in which Johnny Cash voices a mystical space coyote, John Waters endearingly demonstrates the joys of camp—and who can forget the scene where Homer inadvertently takes Bart to a gay steel mill? (“We work hard. We play hard.”)

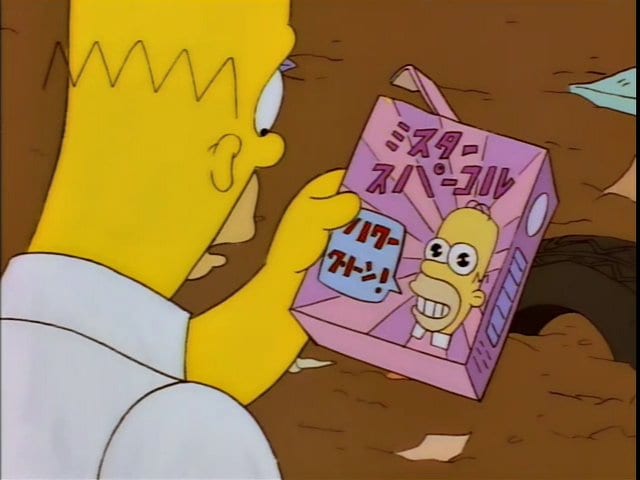

Season 8 also sees Bart working in a burlesque house, Ned Flanders’ memorable tirade against the townspeople after they fail at rebuilding his hurricane-stricken house (“Aw, hell-diddly-ding-dong-crap!”), and perfectly executed crossovers with both Frasier and The X-Files. The season also includes the dark yet brilliant story of Frank Grimes, as well as the delightfully whimsical mystery of Mr. Sparkle (“Wha…Why am I on a Japanese box?”).

The only significant exception to Season 8’s brilliance is “The Simpsons Spin-Off Showcase”—probably the worst episode of The Simpsons’ s entire golden age. This is the episode that satirizes spin-offs and other TV clichés, with a Chief Wiggum cop show, a sitcom starring Moe and Grampa, and a Simpson family variety show. It’s badly written on purpose in an attempt at parody, but to me it just comes across as bad, and I struggle to sit through it. Simpsons showrunner Bill Oakley makes the point that “A viewer’s appreciation of the episode will be vastly greater if he/she has seen the things we are satirizing,” which is fair enough, and I’m clearly not the target audience. Regardless, one dud out of the whole season is pretty good going.

The Writers’ Room

So, what is it that made Season 8 so great? There were undeniably some exceptionally talented writers on the show at the time. The reclusive and eccentric John Swartzwelder wrote the excellent Season 8 offerings “You Only Move Twice” and “Homer’s Enemy,” and was described by fellow Simpsons scribe Matt Selman as “one of the greatest comedy minds of all time.” Meanwhile, George Meyer came up with the ideas that formed the basis for “Hurricane Neddy,” “El Viaje Misterioso De Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyage of Homer),” and “Homer’s Phobia,” and was named by Bill Oakley as “the single most valuable and creative writer in the history of the show,” having “been there since the beginning adding thousands of jokes and plot twists, etc., that everyone considers classic and brilliant.”

Ken Keeler wrote the fantastic scripts for “Brother from Another Series” and “El Viaje Misterioso de Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyager of Homer),” as well as the lyrics for the Emmy-winning song “We Put the Spring in Springfield” from “Bart After Dark.” Greg Daniels came up with the ingenious idea for “You Only Move Twice” before becoming a showrunner on three of the biggest TV comedies of the last 20 years: King of the Hill, the US version of The Office, and Parks and Recreation.

The thing is, all of these writers were around for longer than just one season. Meyer and Swartzwelder, for instance, both joined The Simpsons right at the beginning and stayed with the show for over a decade. Their presence can’t have been the only factor that made Season 8 so special. But what about the influence of the showrunners?

Keeping the Show Grounded in Reality

For Seasons 7 and 8, The Simpsons’ s showrunners were Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein. The pair have been best friends and writing partners since high school, and they started writing for The Simpsons back in Season 3. When they took over as showrunners, they had a few clear goals for the direction of the show. The most significant was to keep the family’s relationships and emotions grounded in reality.

On the DVD commentary for Season 7’s “Home Sweet Home-Dum-Diddly-Doodily,” Bill Oakley emphasized the importance of “having the family have relationships in which they apparently care about each other,” and pointed out that “we tried to have characters behave like real people to some extent in real situations.” Rather than being unique to Season 8, this emphasis on realistic emotional reactions is essentially the defining characteristic of The Simpsons’ s golden age (roughly the first nine seasons).

In its early years, The Simpsons’ s detractors derided the show’s characters as bad influences. Fans, however, saw themselves and their families—flaws and all—reflected in the show. Early seasons often depicted Bart’s misery at school, his struggles to concentrate, and his frustration at being forced to be there. This wasn’t a kid who was written to be a role model, it was a kid who was written to be real. Bart provided a sense of solidarity and solace for many kids watching who were having a hard time at school, either academically or socially.

It may have been a cartoon, but for many people, The Simpsons was one of the most relatable shows out there. Over the years, the Simpson family members fought with each other, frustrated each other, and even failed each other on occasion, but they always loved each other, and they came through for each other when it really counted. The emotional resonance of The Simpsons remained impressive throughout its first seven seasons.

In Season 8, this aspect of the show truly shines, providing the basis for every episode. Even the silliest plots and jokes are centered on the emotional journeys of the characters as they face morally complex situations and tough choices. Hence, Homer working for a supervillain without noticing becomes a story about Homer having to choose between his own happiness at work and his family’s happiness in their lives. The latest Sideshow Bob escapade revolves around Cecil’s jealousy and eventual betrayal of his brother, while Bart wrestles with the decision of whether to give a second chance to the man who once tried to kill him.

When Lisa develops an innocent crush, she and Nelson both have to figure out whether their attraction can overcome their inherently different values. After trying to control Bart’s sexuality, Homer is eventually forced to confront the irrational nature of his homophobia. Even “The Springfield Files,” a relatively silly episode filled with visual gags, contains the through-line of whether Homer’s family believes him or not about his alien sighting.

Sadly, in the years after Season 8, under showrunner Mike Scully (Seasons 9 to 12), The Simpsons seemed to lose its way. Episodes were no longer grounded in realistic emotions—the very thing Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein had emphasized as being so important. Stories became more and more disjointed, seemingly governed by the craziest twists the writers could come up with, rather than by any kind of emotional character journeys.

It was somewhere around “Thirty Minutes Over Tokyo,” the last episode of Season 10, that I think I truly gave up on the show. It’s an episode that’s fairly typical of what I’ve seen of post-golden-age Simpsons, and the show’s decline can be clearly seen in it. The episode bounces around from Lisa trying to convince Homer that the Internet is a good thing, to the family being robbed, to Homer throwing the Emperor of Japan across the room for no apparent reason, to the family going on a particularly cruel game show until finally they’re on a plane that’s attacked by Godzilla.

There’s no sign of a coherent story, no emotional journey for any of the characters (barely any emotion at all, for that matter), and none of the characters’ relationships are explored, put to the test, developed, or are even really relevant. The jokes aren’t even funny—possibly because they’re written as lazily as the story is, or possibly because strong jokes often come from a situation building and building to the point of absurdity—like Homer failing to notice Hank Scorpio’s more and more obvious attempts to take over the world, or Frank Grimes becoming so frustrated with Homer that he makes fun of his dangerous behavior and electrocutes himself. Without cohesive character arcs or realistic emotions, there’s simply no base on which to construct either good comedy or good drama.

While Season 8 builds on what the earlier seasons achieved, it’s clear that none of Season 8’s episodes could possibly have been made much later, because the emotional resonance and coherent stories that made them so great simply wouldn’t have been there.

Exploring Supporting Characters

Another goal that Oakley and Weinstein had as showrunners was to further explore the show’s secondary characters. Weinstein said that “by the 7th and 8th season, we determined people were familiar enough with the characters that we could start exploring their backgrounds and lives a little more in depth, to start rounding out the universe, so to speak.” Again, this wasn’t something that was vastly different from what had gone before. When asked about his own contributions to the show, David Mirkin, showrunner for Seasons 5 and 6, said, “I also brought forth the supporting characters, I did the first story that was about Apu and other various characters that I was interested in bringing to the forefront.”

While earlier seasons did include some stories about secondary characters (mostly dealing with the extended Simpson family and the people the Simpsons worked with or went to school with), in Season 8, Oakley and Weinstein significantly expanded the depth and breadth of the series’ focus to bring us greater insight into characters like Nelson, the Van Houtens, Ned Flanders, Reverend Lovejoy, Mr. Burns, Principal Skinner, and Mrs. Krabappel.

Part of the reason they were able to do this so successfully was that the timing was right. In a show’s early seasons, when viewers are still getting to know the main characters and there’s still so much to be explored there, it makes sense to keep the spotlight on them. The longer a show goes on, the more it makes sense to explore characters on the periphery who can deliver fresh storylines and perspectives.

Many of Season 8’s storylines about supporting characters rely on turning what we know about a character on its head to reveal a surprising new side to them. This could only work with characters who are already well established, and therefore a lot of these episodes couldn’t have been made much earlier than Season 8. The comedy and drama in “Hurricane Neddy,” for instance, comes from the moments when Ned acts in complete opposition to what we’ve grown to expect from him, losing his cool and angrily ranting at the entire town when they mess up his new house.

This simply wouldn’t have the same impact if Ned was a character who had only recently been introduced—if we didn’t have such an ingrained understanding of who we thought he was. Even the explanation of why he talks the way he does—in strings of iddily-diddlies—wouldn’t be interesting if we hadn’t spent years watching him talk like that without knowing why. Of course, the revelations about Ned’s past work so well because, while surprising, they also make total sense when you think about them.

In “Lisa’s Date with Density,” we get to see a more complex and sensitive side of Nelson in his affection for Lisa, but also in his unwillingness or inability to change for her. The glimpse into his somewhat bare-bones home life is equally insightful. While the cockroaches on his door key and his absent parents paint a somewhat depressing picture, I just love the fact that he plays the guitar, and I like to imagine him strumming away every now and then.

Undoubtedly, some of the best moments of Season 8 come from the exploration of secondary characters. Skinner and Krabappel’s romance in “Grade School Confidential” is perfect. The excitement of Reverend Lovejoy fighting off baboons aboard a moving train in “In Marge We Trust” is enough to restore our faith in him as much as it restores his faith in his job. Mr. Burns descending into paranoia with Homer in “Mountain of Madness,” horrifying Lisa with his “recycling plant” in “The Old Man and the Lisa,” and being revealed as the alien in “The Springfield Files” are all classic Burns moments.

Conceptually Experimental Episodes

Oakley and Weinstein’s other major goal as showrunners was to make at least a few particularly experimental episodes. As Josh Weinstein said on the “Homer’s Enemy” DVD commentary, “every year we wanted to do a few episodes that really pushed the envelope conceptually.” In this vein, in Season 8 they made the episodes “El Viaje Misterioso De Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyage of Homer),” “Homer’s Enemy,” and “The Simpsons Spin-Off Showcase.”

While I’ve already discussed my disappointment with “The Simpsons Spin-Off Showcase,” I do think it’s important to take creative risks, and I’d rather have a bad episode plus the ingenious “Homer’s Enemy” and “El Viaje Misterioso de Nuestro Jomer” (The Mysterious Voyage of Homer) than not have any of them. I certainly can’t imagine any of these three episodes being made in The Simpsons’ s earlier years. Whether or not the show’s viewers would have been ready for such experimental episodes when they were still getting to know the show and its characters is up for debate, but the writers and showrunners of earlier seasons weren’t willing to take the risk.

This is evidenced by the fact that “El Viaje Misterioso de Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyage of Homer)” was actually pitched by George Meyer several years before Season 8, but, as he said on the DVD commentary for that episode, “it at the time seemed a little bizarre to people, I think.” On the same commentary, Simpsons creator Matt Groening elaborated: “I loved it, and everyone else in the room was freaked out by it, and they got very quiet, because it was pretty crazy, involving hallucinations.” The idea may have been too crazy for most of the staff at the time, but thankfully in Season 8, Oakley and Weinstein were able to resurrect it.

The episode is unlike anything else The Simpsons has ever done. The different animation styles used to create the extended hallucination sequence are outstanding, making us feel like we’re on a mystical journey along with Homer. Johnny Cash is, of course, fantastic as the coyote. There’s something unique and utterly compelling about the episode, yet it still feels like The Simpsons. Beyond the incredible visuals and the whimsical story, it’s packed from start to finish with some of the funniest jokes in the show’s history, and it’s all grounded in a realistic emotional arc as Homer questions whether Marge is truly right for him. It might just be The Simpsons’ s best episode.

Another classic, “Homer’s Enemy,” deconstructs the entire concept of The Simpsons and the character of Homer by having Frank Grimes point out how ridiculous and frustrating Homer would be in real life—and how much danger he would constantly be in. This is probably the darkest Simpsons episode of all time—as well as the most meta. It’s one of those episodes where you can’t quite believe the creators really dared to go there. Frank Grimes’s depressing life and shocking death are seared into the minds of fans everywhere, as stark reminders of the unfairness of life and the plot armor constantly surrounding Homer Simpson.

Oakley and Weinstein knew that the risks they were taking might not be popular, but they believed them to be worth taking anyway. As Oakley said, “We were well aware that not every episode we produced would appeal to everybody—even at the earliest stages of […] Frank Grimes, et al., we knew there was no chance that more than 20% of the viewers would understand or like what we were doing […] But that is the great thing about the Simpsons—we got the opportunity to TRY these weird things.” The duo’s willingness to experiment, and their acceptance that the results might not be widely appreciated, was vital in bringing the world such genius episodes as “Homer’s Enemy” and “El Viaje Misterioso De Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyage of Homer).”

Tackling Controversial Topics

Oakley and Weinstein’s experimental attitude extended beyond just pushing the envelope conceptually and exploring secondary characters. In Season 8, they also decided to tackle a couple of subjects that were more serious and controversial than anything the show had dealt with before.

In the great episode “A Milhouse Divided” and the absolutely phenomenal “Homer’s Phobia,” divorce and homophobia are each addressed in nuanced, complex, and funny ways. “Homer’s Phobia” is simultaneously one of the most meaningful, important, and fun episodes ever made. Homophobic attitudes are sharply satirized and shown to be completely irrational through Homer’s ridiculous arguments, including his insistence that it’s John’s sneakiness he objects to (“You know me, Marge. I like my beer cold, my TV loud, and my homosexuals FA-LAMING!”). Homer’s attempts to turn Bart straight are equally absurd and backfire hilariously. Peppered throughout the satire and the serious themes are countless delightful moments and jokes that make this one of the most enjoyable Simpsons episodes by far.

While topics like divorce and homophobia certainly wouldn’t be as controversial to address now, it seems unlikely that these episodes could have been made in the show’s earlier seasons. In fact, when the original script for “Homer’s Phobia” was sent to the censors, they sent back three whole pages of notes. According to Oakley, “They felt the whole episode, the whole area, was unsuitable for broadcast and then, additionally, felt every single line mentioning the word ‘gay’ or dealing with the topic at all had to be deleted or replaced.” It was only when the president of the network happened to be fired, and a new president was installed, that the censors deemed the episode acceptable—clearly Oakley and Weinstein really were pushing the envelope thematically as well as conceptually.

Exploring Different Locations

In Season 8, Oakley and Weinstein were also starting to explore new locations to set episodes in. This led to the creation of episodes like “You Only Move Twice” (where the family moves away from Springfield to Cypress Creek), “Bart After Dark” (where Bart starts working in a burlesque house), and “The Secret War of Lisa Simpson” (where Bart and Lisa go off to military school). The idea for Bart and Lisa going away to military school was actually pitched years before Season 8, but on the DVD commentary for “The Secret War of Lisa Simpson,” Matt Groening said, “We weren’t comfortable with taking the kids away from home that early on in the series,” proving yet again that some of Season 8’s best episodes could never have been made earlier in the show’s run.

It’s true that it was a somewhat daring move to take the Simpson kids away from Springfield and their parents. Ditto having the family actually move away from Springfield in “You Only Move Twice,” and having the 10-year-old Bart spend most of an episode in a burlesque house. New locations also demanded a lot more work from the animators and directors, who had to design new sets from scratch. Still, these episodes turned out great, yet again demonstrating the value of having showrunners who were willing to take a few risks. A world where we’d be deprived of Hank Scorpio’s encouraging chats with Homer (“Relax, Homer, at Globex, we don’t believe in walls!”), or of Grampa and Principle Skinner visiting the Maison Derriere only to be confronted by Bart just doesn’t bear thinking about.

As well as being a fun episode with a catchy song and a ton of great jokes, “Bart After Dark” also contains some interesting examinations of morality. Homer does genuinely try to do the right thing when forcing Bart to work off the damage he caused, and it’s arguably one of his better parenting decisions, though it’s turned on its head when it turns out Homer is insisting his young son works in a burlesque house. Marge and the religious characters clearly think they’re doing the right thing in their crusade against burlesque when they’re actually just doing exactly what Bart was being punished for in the first place—trespassing and damaging Belle’s property—as well as trying to police the morality of the entire town.

For her part, Belle seems to be a nice and capable businesswoman whose clients and employees are perfectly happy, and she even acts as a kind of mentor to Bart. In fact, in this episode Bart seems to actually develop a work ethic and a sense of responsibility for once, indicating that Homer’s punishment may have been quite effective after all.

Resurrecting Old Ideas

It’s striking that several Season 8 episodes are based on ideas that had been floating around for years. “Lisa’s Date with Density” and “Grade School Confidential” both deal with romantic pairings that had been suggested before but that didn’t materialize until Oakley and Weinstein were looking to explore secondary characters in much more detail. “El Viaje Misterioso de Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyage of Homer)” had been pitched early on but deemed too weird, only being made when Oakley and Weinstein wanted to make more conceptually experimental episodes.

Elements of “Homer’s Phobia” had also been around for a while, but the episode didn’t come together until Oakley and Weinstein decided they were willing to tackle more serious topics than the show previously had. The idea for “The Secret War of Lisa Simpson” had also been around for years, but didn’t get off the ground until Oakley and Weinstein decided to explore new locations and take the family further afield.

This resurrection of old ideas doesn’t seem to have happened often in other seasons. It further demonstrates that in Season 8, many ingenious ideas were finally allowed to flourish when they clearly wouldn’t have been (and indeed weren’t) in earlier seasons. Interestingly, it also suggests that another factor in making Season 8 so great was that Oakley and Weinstein had several years’ worth of great ideas to choose from. These ideas had assumedly been piling up, deemed too weird, too different, or too risky since The Simpsons began. Suddenly, the show was finally in a place where it made sense to use them and had showrunners who were open to doing so.

In theory, then, Oakley and Weinstein were able to simply pick the best of several years’ worth of these ideas, adding them to the best of the new ideas for Season 8. This had to have provided a further boost to the already outstanding season in a way that couldn’t be done in any other year of the show. Assumedly, by Season 9 the best of those ideas had been used up, and the writers had to go back to the drawing board.

Putting Trust in Their Fellow Writers

Oakley and Weinstein seem to have put a lot of trust in their writers, which—along with being open to taking risks—is a great way to encourage maximum creativity. As Weinstein said, “we’ve always been big believers in the group effort, where we really listen to people under us (you never know where a great idea might come from), and when those people demonstrate their abilities, we place more trust in them—for example, we would often have two rewrite rooms going at once, and sometimes one of these rooms might be run by a senior writer, like David Cohen or Steve Tompkins.”

In contrast, their predecessor David Mirkin preferred to be in control: “When I was running the show, we just had one room. I have a tendency to control most things and felt I had to be in the room pretty much for every moment. […] If I had to go direct the actors, all the writing would stop; if I had to go edit the episodes, all the writing would stop.” This is, of course, an equally valid way of working, and the seasons run by David Mirkin were undisputedly brilliant.

However, there is something to be said for an approach that prioritizes the best ideas—no matter who they come from, how experimental or weird they are, and whether they’re new or old. While most of Season 8’s excellent writers were on the staff for several years, it’s possible that Oakley and Weinstein were able to truly make the most of having such good writers around and utilize their talents better than any other showrunner by putting their trust in them, encouraging ideas that would have been dismissed as too risky or poorly-timed in earlier years, and finally bringing their best older ideas to life.

Finding Their Stride as Showrunners

Under the leadership of Oakley and Weinstein, Season 8 seems to have been the perfect time in The Simpsons’ s history for great writing to flourish. Not long after Season 8, the emotional realism that kept the show grounded was lost. Much before Season 8, the show’s writers weren’t yet ready to explore the themes, characters, locations, or experimental formats that made Season 8 so compelling.

One remaining question is: why is Season 8 better than Season 7? Both seasons were run by Oakley and Weinstein, and any ideas that wouldn’t have worked much earlier in the show’s run would have worked just as well in Season 7 as in Season 8. The only guess I can hazard is that perhaps it took some time for Oakley and Weinstein to properly settle into their new roles as showrunners, and that with experience they finally gained the confidence and skills to make the ultimate Simpsons season.

One more thing to bear in mind is that, while there is a significant drop in quality after Season 9, the difference between Season 8 and the rest of the golden age is much more subtle. The first nine seasons are all excellent—it’s just that Season 8 seems to have a much higher concentration of episodes that are utterly outstanding, rather than just The Simpsons’ s regular level of brilliance. Season 8 was essentially the pinnacle of an already amazing show—it was when The Simpsons finally reached its full potential. Despite the disappointment many of us feel with the show’s eventual trajectory, back in Season 8, The Simpsons was truly something special, and we can continue to cherish those classic episodes for years to come.