Futuristic, anti-gravity racing games were all the rage in the latter half of the 90s. The advent of 3D polygonal consoles had enabled developers to create games where vehicles could travel at incredible speeds on tracks that could twist and loop without concern for real world physics. Many great games emerged from this compelling formula—Extreme-G, Rollcage, Star Wars Episode 1: Racer—but two titles undoubtably stood at the top of the pile: F-Zero X and WipEout. Below their superficial similarities lay an opposing ethos of game design, one that would signal a split in the games industry—a split that we still see to this day.

F-Zero: A Genre is Born

The original F-Zero was released for the Super Famicom in 1990—later coming to the Super Nintendo in North America and Europe in 1991 and 1992 respectively. The game was revolutionary at the time for its extensive use of ‘Mode 7’ graphics which enabled the 16-bit Super Nintendo to emulate 3D environments. ‘Mode 7’ allowed developer Nintendo EAD to give the game a genuine sense of movement and speed. It also enabled them to create tracks that were filled with tight turns and huge jumps. It was a striking leap from the 8-bit, rolling road type racing games that had existed on home-consoles before.

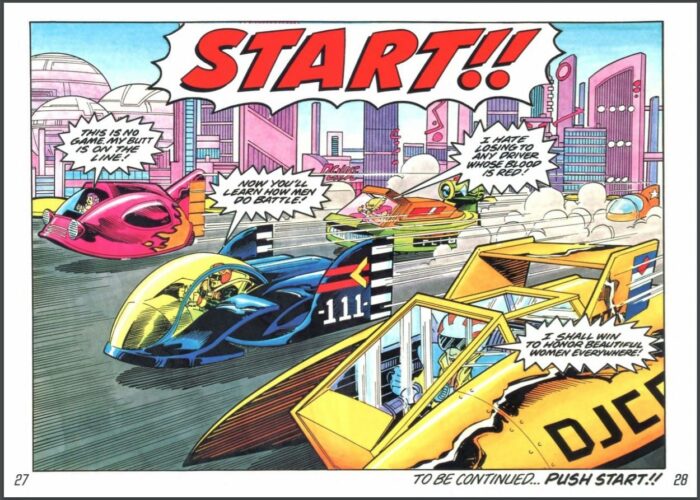

Though the game itself focuses purely on the racing action, the game’s manual goes to great lengths to set the scene, even culminating in a seven-page comic strip. Set in the year 2560, F-Zero takes place in a pulpy world of corrupt multi-billionaires and bizarre alien species, where dangerous sports have been created to satiate the wealthy elite. A colourful cast of four playable racers and machines were created for the game, each with their own motivations and backstory. The mercenary alien, Pico and the wealthy genius, Dr Stuart take a back seat to the rivalry between crime boss Samurai Goroh and the heroic bounty-hunter named Captain Falcon. F-Zero’s character designs and locations look like they were lifted straight out of a 70s or 80s comic.

Whilst the game was a critical and commercial success, somewhat surprisingly, few developers at the time attempted to imitate it. As such, its legacy as the grandfather of the futuristic racing genre wouldn’t become apparent until several years after its release. In fact, F-Zero itself wouldn’t get a sequel until 1998 with the N64’s F-Zero X—a full 8 years after the original game’s release. In the meantime however, a new exciting franchise had taken the futuristic racing genre into uncharted territory.

WipEout: The Breakthrough Artist

WipEout released alongside the Sony Playstation in 1995. Though it would later appear elsewhere, it became synonymous with Sony’s ground-breaking 32-bit system. Developed by Liverpudlian studio Pysgnosis, the game seemed to pay little homage to Nintendo’s F-Zero. In stark contrast to the camp, comic-book sci-fi vibe, WipEout was ultra-modern, stylish, grown up and above all else, it was effortlessly cool.

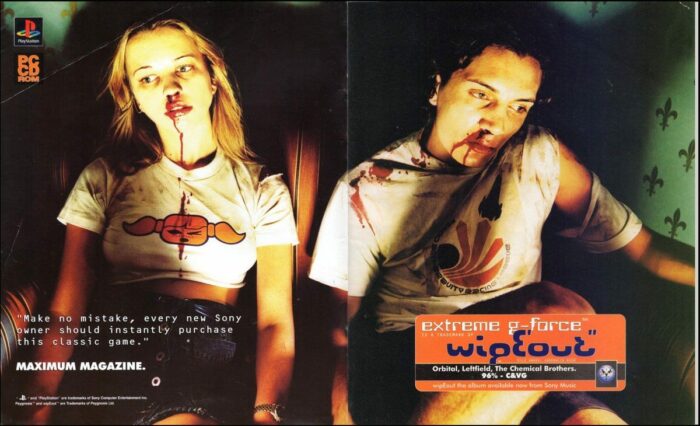

Upon its release, the game’s marketing was targeted at young adults and focused on the thriving UK club culture. Pysgnosis had reached out to The Designers Republic to work on the game’s cover art, logos and promotional posters. The Sheffield based graphic design studio were well known for their brash, stylised, satirical takes on hyper-consumerism and had worked on numerous album covers for various contemporary electronic artists. The cover-art and logo gave the game an instantly iconic style and a controversial poster featuring a nose-bloodied, spaced-out Sara Cox (perhaps alluding to a drug overdose), which raised more than a few eyebrows—WipEout wasn’t for kids.

The final piece of the zeitgeist puzzle was an incredible electronica inspired soundtrack, backed up by licenced tracks from Leftfield, Orbital and The Chemical Brothers—three UK dance artists at the peak of their success. The perfect storm had been created—WipEout had managed to successfully integrate itself into culture mags, night clubs and music festivals. It had broken boundaries and separated itself (and in turn, the Playstation) from the childish stigma of gaming.

Perhaps it’s rather telling though, that it’s taken me three paragraphs to finally get to the video-game that sits behind the logos, marketing and soundtrack. WipEout certainly isn’t a bad game but it’s far from a great one. The gameplay is fairly standard fare for the genre and at surface level shares much in common with F-Zero—a three-lap race, with the player starting from the back of the grid and having to work their way to first place.

WipEout’s vehicle physics feel weighty, slow and strangely realistic—you really get the sense of the ships bouncing and sliding on a cushion of air. It leads to a slightly frustrating experience during the tighter, twistier sections of the tracks though as you find yourself helplessly understeering into the walls. Doing so will bring the craft to a grinding halt, instantly scrubbing off any speed and momentum you had built up.

WipEout is an exercise in patience, persistence, and memorisation. Items and weapons can be picked up along the track to help the player deal with the aggressive A.I. racers. A bizarre system of symbols denotes which item you have picked up and it can be difficult to figure out whether you’re about to fire a rocket, drop a mine, or boost yourself into a wall. In any case, few of the items seem to do much good. Shooting down an opponent ahead often results in you merely crashing into the back of them—rarely do the weapons help you progress. Fighting in the mid pack in WipEout reminds me of how live crabs can be easily contained in an open bucket—as each crab tries to climb out they pull back on another preventing their escape.

WipEout’s gameplay isn’t perfect but the core experience is certainly compelling enough. The game is challenging but ultimately rewarding to overcome. The electronic soundtrack suits the mindset you need to be in to play it. Sink back into something comfy, let yourself be absorbed and fall into a trance—fail, try again, repeat. Regardless of any flaws, WipEout had set the new benchmark for the genre and in turn unleashed a wave of clones to follow for years to come. If F-Zero was the grandfather of anti-gravity racers, WipEout was the daddy.

F-Zero X: Function Over Form

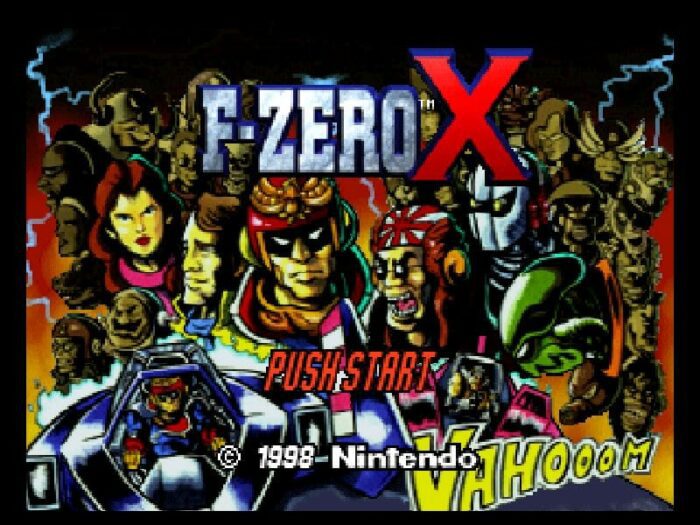

F-Zero X finally released in 1998, by which point its rival had already spawned its own sequel in WipEout 2097 (a minor iterative improvement on the original). It took the foundations that its predecessor had laid out and launched it, quite literally, into a new dimension. Just as Pysgnosis had wanted to carve their own path in the genre, Nintendo clearly weren’t interested in piggy backing off of WipEout’s success—F-Zero X was the antithesis of WipEout. It was loud, blisteringly fast, and ran at a silky smooth 60fps with a hugely impressive 30 racers on track. The graphics were plain—ugly even. It was a die-hard commitment to function over form at a time when graphics were praised above all else. The soundtrack was metal and a decade out of date—music for social outcasts, not trendy club-goers (It was also brilliant).

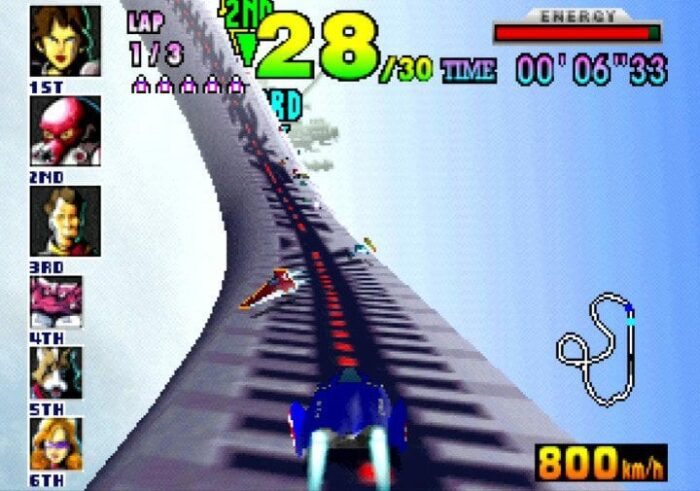

The gameplay in F-Zero X is nothing short of sublime. The ships change direction like pinballs and accelerate like them too. An airbrake allows the player to dive into right-angle corners at full speed. A barge attack allows for violent and visceral assassinations of competitors.

Despite its plain visuals F-Zero X still manages to ooze character. All thirty vehicles on track are completely unique—both visually and in terms of performance. The designs vary wildly in both livery and shape—some are built like tanks, others are as sleek as a fighter jet. The pilots are even more diverse and drawn in the same comic-book style that we saw in the original game’s manual and each are given their own backstory.

I honestly think you could take any one of the characters from F-Zero X and give them their own video-game or comic to star in—you can tell a lot of fun went into creating them. I don’t think you could create a 240-year-old zombie named The Skull, who was resurrected from the grave to compete in a futuristic racing league, without having a sense of humour.

The tracks themselves are full of personality too. Fire Field has incredible verticality and a huge death-defying leap that has your craft soaring whilst trying to find a safe landing amongst the winding track below. White Land 2 has you racing inside a halfpipe, as you try and fight to keep the craft from being flung out. Big Blue has you racing on all sides of a magnetic cylinder. The course designs are closer to rollercoasters than they are race-tracks—they even succeed in giving you that pit of your stomach feel as you twist and turn in all directions.

Above all else though, F-Zero X’s greatest strength is in its sense of speed. Littered around the courses are boost pads which give your craft a surge of acceleration. On the second lap of each race ‘boost power’ is activated, allowing the player to continuously build their momentum—at the expense of their life bar. A typical race in F-Zero X sees you furiously boosting to the line, spending your last reserves of health as your vehicle flashes red in distress. It’s a glorious way to climax an already adrenaline filled experience. If the right state to enjoy WipEout is trance-like, the right state to enjoy F-Zero X is wide-eyed and on the edge of your seat.

Nintendo and Sony: Gaming’s Yin and Yang

It’s amazing then that F-Zero X and WipEout, which on the surface seem so alike, can be so different. What’s more surprising is how their stark differences have been indicative of the paths that Sony and Nintendo would later follow.

WipEout showed Sony the power of marketing in video-games and the value in targeting a zeitgeist. It was the first time that a video-game had been considered ‘cool’ amongst young adults and twenty-somethings—the same demographic that Playstation would continue to target hardest and have ever since. Playstation became a gadget, a multimedia system, something that no adult should feel embarrassed about owning and that reputation remains to this day.

Soundtracks containing licenced tracks would become commonplace in Sony developed and published games. Gran Turismo, Cool Borders, and Twisted Metal were contemporary examples but the practice is equally common today and can be seen in the likes of Death Stranding and Drive Club.

Sony have also continued to push graphical fidelity as a primary focus in their games. Just as WipEout’s spectacular visuals blew away gamers in 1995, Playstation exclusives such as God of War and Horizon Zero Dawn continue to push the boundaries of home-console graphics.

Nintendo however, have stoically resisted these industry trends, even when it seemed to harm their own market share. From the N64 to the present day, their hardware has been behind the curve (at least in terms of raw performance) as such gameplay has always been the focus. Where other companies have fixated on adding more realism to their games, Nintendo have continued to prioritise ‘fun’ above all else.

They’ve also emphasised the importance of keeping their games family friendly and fun for all. While in charge of the company, the late Satoru Iwata was quoted as saying “I’ve never once been embarrassed that children have supported Nintendo. I’m proud of it.” A stark contrast to the message behind the infamous WipEout poster of Sara Cox with a bloody nose.

These days, the F-Zero and WipEout series’ have now all but faded into relative obscurity, to be mourned only by an old guard fanbase. In terms of video-game history however, no one could doubt the legendary status of F-Zero X and WipEout. They were two rival games which perfectly encapsulated the essence of Nintendo and Sony’s yin and yang approach to the game industry.