I love Deadwood. It’s easily in my top five of shows that I rewatch over and over again. Top three, even. I’ve met some wonderful people through the fandom. And like with any fandom, while I’ve really connected with some fans, I’ve also met some people I just don’t relate to, even when all we talk about is the show. I’ve pondered this, and I think it’s because Deadwood is two shows at the same time, each with its own appeal.

We all know that Deadwood is a realistic (read: gritty AF) gold rush-era Western, set in the real town of Deadwood, in the Black Hills of South Dakota. In a town with no laws, you’ve got your historically accurate racism, sexism, and addiction everywhere, to say nothing of the fact that a human life could be tossed away over something as trivial as a hand of cards. It’s a show where the language, for all its flowery, Shakespeare-like beauty, is so profanity laden that to play the eponymous drinking game (a shot every time someone says “cocksucker”) would land most of us in the hospital halfway through the pilot. There’s fightin’, cussin’, drinkin’, gamblin’—nudity, both attractive and the other kind, and everything is ankle-deep in mud and sweat. It is all of these things.

But David Milch’s Deadwood is two shows at once. It is absolutely possible to watch Deadwood for what it is on the surface: all that wonderful, aforementioned grit. It is possible to love it for those things alone—if you like badassery, you’re not going to get much better than this. However, if you want to, you can look a little closer.

David Milch is a writer that wants you to work. For him, a scene isn’t about the dialogue—it is about what isn’t being said, and therein lies Deadwood’s real beauty. At its core, what we have here is a bunch of rough, primal people, in some of the worst possible circumstances, trying to not only exist, but in many cases, to take care of each other. The duality I have discovered in the fandom is representative of the duality of the show itself—the Type A fans, who want to take it at face value (nothing wrong with that), and the Type B, who are there for the subtext and what’s going on behind what the characters are actually saying. I don’t presume to compare the two types of fan…but I’m Type B, if you haven’t guessed.

At first glance, Deadwood is apt to raise the hackles of anyone who has ever even thought about feminism. And why not? Ninety percent of the women are employed as whores, and the few women who aren’t whores are either the rich lady who uses opiates to get through her day in a loveless marriage, or the drunken gunslinger “Calamity” Jane Cannery (Robin Weigert), who spends most of her time either shouting at the world, or drinking to help her escape it. One of the first women we meet is the whore Trixie (Paula Malcomson), who right from the start insists on agency of her own, insofar as she is able—a customer won’t stop beating her, so she shoots him through the brain. When this results in further beating at the hands of her pimp, instead of submitting to further abuse from clients, she gets another gun.

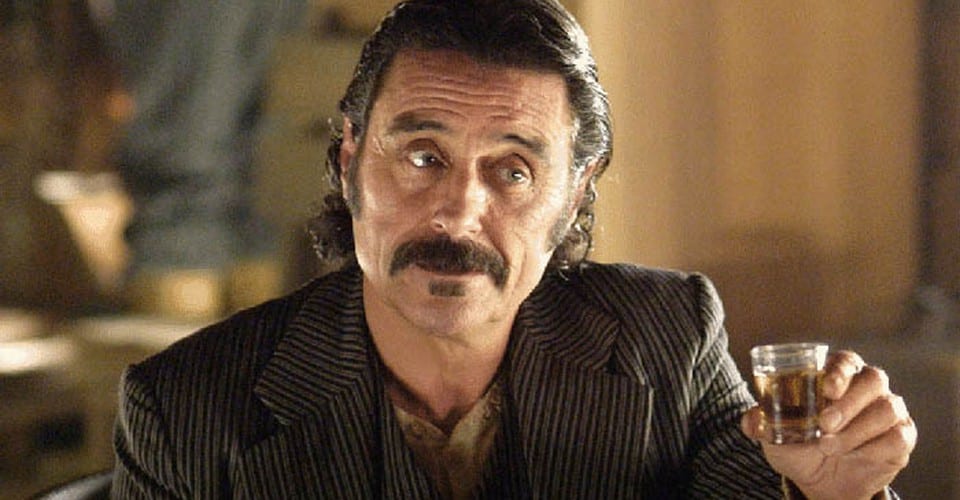

Al Swearengen (Ian McShane) is more than just a pimp—he runs the town. Whores, booze, games, drugs, you name it—Al has his hands on it in some way. It would be easy to leave it there, for Al to be no more than a male power fantasy made flesh. But Milch doesn’t work that way. His characters are real people, and they are complicated. The more time we spend with Al, the more we learn about him. We learn of his past, his youth spent abused in an orphanage, or growing up on the streets, as he puts it—“cutting throats”. We learn that, in every whore he runs, he not only sees the mother who abandoned him, he sees himself, and we see a desperate need to nurture—to take others under his scarred and filthy wing, and protect them the only way he knows.

Trixie is his favourite—she may spend her days servicing paying customers, but she spends her nights in Al’s bed, cuddled up like any married couple. Their love for each other is unhealthy, to say the least—but it is real, and it is strong. When she encounters a chance to better herself, her life, and her love, Al kicks her out the door—but really, it is a kick out of the nest, at the cost of his own heart. Anyone who says Al Swearengen is not a feminist is not looking carefully.

Seth Bullock (Timothy Olyphant) is the reluctant lawman, whose smouldering intensity and hot temper become adorable if you stare long enough. He falls madly in love with Alma Garrett (Molly Parker, see above rich lady on opiates), and she with him. Unlike the whoring that takes place out in the open and no one bats an eye, their affair is torrid and tucked away, the product of dark rooms and whispers in the corridor. He bears the cross of being married to his late brother’s widow, raising her son as his own. When his wife is introduced in Season 2, it is another loveless marriage…until it isn’t. Olyphant himself has described Deadwood as “a show about a man who learns he loves his wife”.

I cannot even begin to tell you how many Seth/Alma shippers I have had to conversationally walk away from—you do you, after all, and I’ll do me—because they insist that Seth and Alma have one of the great romances of the age, and they loathe his wife Martha because she gets in the way of that. I don’t argue, except to suggest that they sometime read up on what the actors themselves have said about the relationship (Molly Parker has described Seth as just another addiction for Alma). Hot? Yes. A great and abiding love? I don’t think so.

Martha Bullock is played by the brilliant Anna Gunn, in yet another role that vilifies her to fans because she gets in the way of their ship or power fantasy (see Skyler White, whom I also love). God, she’s good. I always think of her as the female Richard Schiff (and if you don’t know what that means, you need to go watch The West Wing until that description makes sense). Her strength is a quiet one. She’s one of the few characters who practices verbal restraint, with not a touch of profanity escaping her lips. When she arrives in town with her son, she quickly learns of her husband’s relationship with another woman, and when he promises that he will end it because honour insists, she tells him (politely) to shove it. She wants no part of his second-hand, leftover love.

Then, when she is struck by the worst tragedy a mother can endure, she finds her solace in nurturing others—she forms a school, and offers to teach the other children in the camp—including Alma’s adopted daughter. That’s two deep hurts that Martha is able to bear by helping others. It’s hard for me not admire that…but to far too many fans, all they see is the dull wife who gets in the way of Seth and Alma. In the movie (set a decade after the events of the series), Seth and Martha are thriving, with a bunch of kids, and a happy home. When he sees Alma for the first time in a long time, sure, he has a moment of “what if” (he’s only human, after all), but it passes quickly. He contentedly goes home to his family, and Alma, winning my respect for one of the few times in our acquaintance, doesn’t try to mess with that.

One of the more heart-wrenching characters, for me, is the camp’s doctor, Amos Cochran. Anyone played by Brad Dourif is going to be a gorgeous pastiche of human complexities, and Doc Cochran is no exception. A veteran of the Civil War, he has come to this place to deal with his own post-traumatic stress nightmares by using his limited skills to ease suffering here, in any way he can. He takes care of the girls in all the whorehouses, even when he isn’t paid. He helps the camp cripple to walk more easily, his only hesitation coming from fear that he might do her further harm, because his conscience can bear no more. When he discovers that the bristly Calamity Jane has a talent for healing, he nurtures it and gives her an incredible gift—a sense of self-worth. He never really realizes that these things are balm for his own tortured soul.

Speaking of Jane and shipping, Jane and Joanie Stubbs are adorable together, on the surface. I wanted them to get together as much as anyone—hell, as much as Charlie Utter (Dayton Callie), who set them up in the first place (Charlie Utter is really such a yenta). When the movie happened and they weren’t together anymore, I wasn’t really surprised. For all their talk of reconciliation and Paris, I’m not sure about the future of these two. Primarily, Jane was never with Joanie because she is attracted to women…Jane is a broken soul who wants someone to be kind to her. She felt that way about Wild Bill Hickok, and her crush was probably more than friend-crush, though she seemed fine with whatever kindness and attention he was willing to give her. Joanie is broken too, through years of systematic abuse by men. Would she have grown up preferring women if her daddy hadn’t been a slimeball? There’s no way to know.

It never surprised me that Joanie ran the girls for Cy Tolliver, or that she took over running the Bella Union when Cy (presumably) died. Running the girls and manipulating the male clientele (even the friendly ones, like Ellsworth) are the only things that give Joanie any sort of control—control she doesn’t even recognize as strength. When Charlie nudges her and Jane towards each other, it’s almost as if she doesn’t know how to be or have a female friend. When Jane suggests that the friendship become sexual (though she is plainly terrified of the unknown), it’s as if Joanie leans into it because she’s finally on familiar ground. Sex is something she knows how to do, and when it’s with someone like Jane, Joanie gets to be the savvy one, and that has to feel comforting. And of course, if you don’t want to put all this thought into it, it is perfectly satisfying to squee at the adorable lesbian couple being adorable.

Even when the complexities of the rustic gangland plot are a little hard to follow the first time through (I promise, you will rewatch it many times, if you haven’t already done), you love these people. You are invested in their lives. You watch them stumbling, clumsily trying to care for one another, all the while wishing you could take care of them. And maybe that’s not why you like the show. Maybe you are Type A, there for the surface of the lake, for the badassery, for the guns and cussing. And that’s okay too. Deadwood is more than one show, the way that human life is more than that which is easily apparent. Like humanity itself, it asks you to look a little closer.