In The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare famously states that ‘the quality of mercy is not strained’. In Ratched, Ryan Murphy strains just how far the quality of mercy can reach. Nurse Ratched is a character whose name strikes fear into many people’s hearts. She is a symbol associated with the dispassionate mental health system, a woman whose personality is synonymous with icy order, callous torture and unkind wit. How do you transform such an iconic villain, whose backstory is a blank slate, into an angel of mercy? Ryan Murphy and his team have attempted such a feat and have overall provided a fascinating glimpse into the intersection between mental health and art.

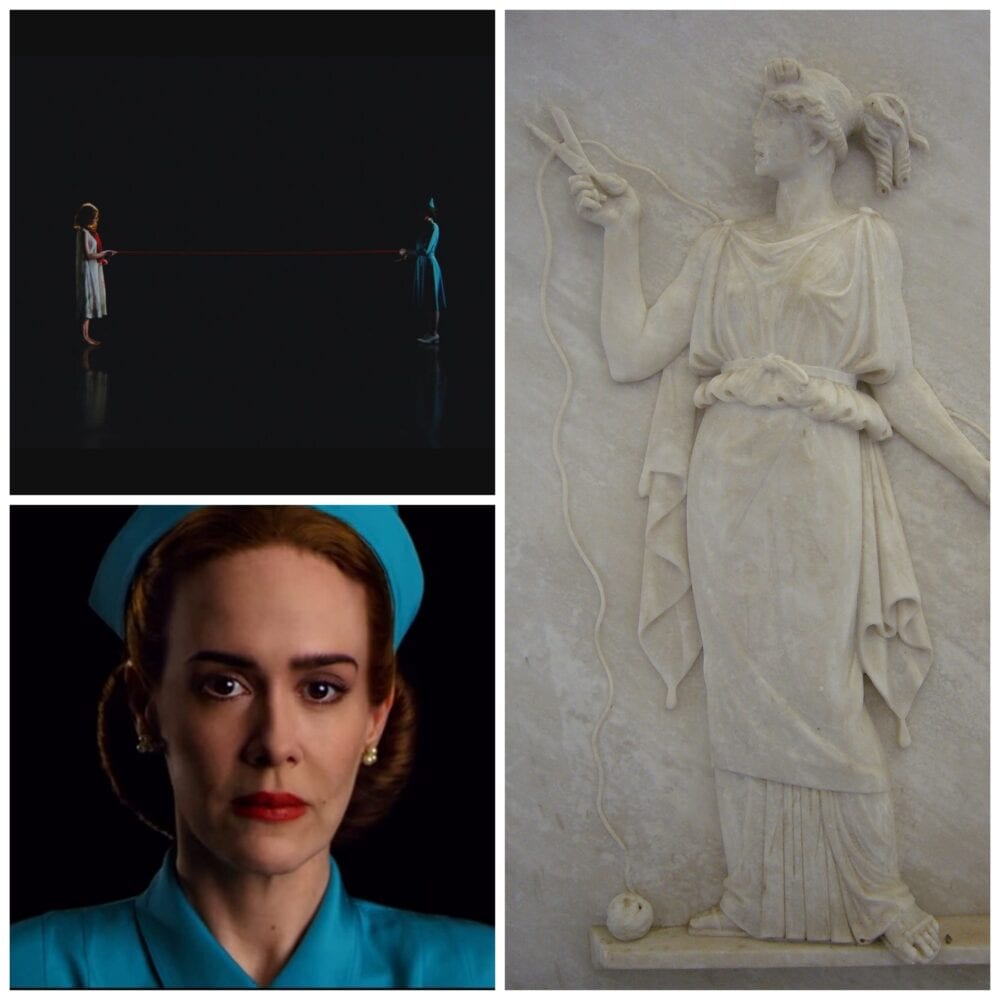

Nurse Mildred Ratched first appeared in the public eye through literary form in Ken Kesey’s seminal 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Described as a doll-like woman whose rosy exterior betrayed a temperament of steel, Nurse Ratched was presented as the nemesis of anti-authoritarian patient, Randle McMurphy. Her name is a play on words, as Mildred means ‘gentle and strong’ while ‘Ratched’ conjures up a tool that allows mechanics to only flow in one direction. Mildred Ratched was given a cinematic form in 1975, when the brilliant Louise Fletcher incarnated her repressed anger and dictatorial control in an Oscar-winning performance. It is now the turn of Sarah Paulson to inherit this monumental role, and in this eight-part series she manages to do something many may think impossible: to make viewers feels sympathy for Nurse Ratched.

One thing that I have always loved about Ryan Murphy’s series is that the opening credits are visually intriguing and often provide crucial information about the plot. Ratched’s opening credits are no different, as we see a series of patients waltz through abandoned wards and forests, all set to Camille Saint-Saëns’ ‘Danse Macabre’. This piece of classical music was written to bring forward scenes of Death as a tempting force and foreshadows how Nurse Ratched’s incredible force of persuasion is used to bring about the downfall of several characters. Moreover, towards the end of the opening credits, Mildred is seen cutting the red thread her patients are carrying, a possible reference to Atropos, the last of the Three Fates who in Greek mythology was in charge of cutting the thread of life with her scissors.

We are properly introduced to Mildred Ratched during the beginning of her nursing career, as she worms her way through different positions at the St. Lucia Hospital in California. However, her rise to the top is not easy, as she has to face off several foes, as well as confront the trauma of her past. Ryan Murphy has said that he envisioned the trajectory of this series as a culmination of battles between Mildred and a male adversary each season. However, is it hard to decipher which man is Ratched’s real enemy. There is Dr Richard Hannover (Jon Jon Briones) the mild-mannered but ambitious head of the hospital who is convinced that anyone can be cured of mental illness, regardless of the methods used.

Another particularly unsympathetic character is Henry (Brandon Flynn), a quadruple amputee whose spoiled demeanour and psychopathic tendencies are highly reminiscent of Dandy Mott, a character from Murphy’s fourth season of American Horror Story. Notwithstanding, the male rival who bears more significance is Edmund Tolleson (Finn Wittrock), who in pure Murphy fashion, is a young murderer who is interned in the hospital for killing four priests. Tolleson is the Randle McMurphy of the series. While Mildred is presented as frigid and manipulative, Edmund is hot-blooded and values sexual attraction over everything. His affair with Dolly, which leads to catastrophe for the hospital draws comparison with the 1975 film, when McMurphy brings two prostitutes to the wards resulting in a chilling manifestation of Nurse Ratched’s fury.

No show would be complete without its main character and Ratched delivers a brilliantly compelling one. Sarah Paulson’s portrayal of Mildred Ratched is more heir to Louise Fletcher’s poised and self-assured performance than to Ken Kesey’s wilder version. This works in her favour, as Fletcher’s Nurse Ratched is mysterious and Paulson manages to imbue her with humanity. Moreover, adding a powerful narrative dimension to this new series, Paulson’s Nurse Ratched is lesbian. When Mildred arrives at the St Lucia Hospital, she is witness to all sorts of medical atrocities. She is fascinated by the lobotomy and is not afraid to execute one herself unsupervised. Nevertheless, when it is the turn of two lesbians who are subjected to hydrotherapy, Mildred is horrified as she realises that her love for another woman would merit the same treatment. I remember seeing a tweet last year that affirmed the reason why queer people often favour the villain of a story is because the media has spent decades queer-coding villains. When I first saw One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest as a naïve gay teen, I thought Nurse Ratched had the big potential to be a repressed lesbian, but now Ryan Murphy has expanded that theory and turned it into a beautifully endearing relationship.

Seeing Mildred Ratched navigate her internalised homophobia brought back a lot of painful personal memories. For many queer people internalised homophobia is a nasty beast, it is something that turns inward and attacks the very foundations of your personality. Mildred comes from a broken childhood, the details of which I will not spoil, a backstory that has haunted her whole life. She believes herself to be unlovable and finds it hard to open up to people. It takes the patience and kindness of Gwendolyn Briggs (a stunning performance by Cynthia Nixon) to give Nurse Ratched inner acceptance. Gwendolyn works for Governor George Wilburn (Vincent D’Onofrio), a man who is hell-bent on executing Edward Tolleson in order to renew confidence with his voters. She is also in a lavender marriage (a marriage of convenience where both partners are queer but are wedded to keep up social expectations) and this was a pleasant surprise, as it is a part of gay history that is not normally shown on screen.

As soon as she lays eyes on Mildred, Gwendolyn is instantly enamoured and what follows is a wonderfully memorable relationship. At first Mildred is hesitant, anxious to secure her place at the hospital and denying her love for Gwendolyn. But soon she realises that if she must survive the trials and tribulations of working at a mental institution, she needs a steadfast partner to keep her level-headed. Out of the many cute moments Mildred and Gwendolyn share together (which include an erotically charged oyster eating scene) my favourite is a small moment that takes place during a dance that Mildred organises for the hospital staff and patients. Mildred arrives in an entrancing teal-coloured dress and she and Gwendolyn look on as a slow dance between the couples takes place. ‘Look at us just standing here’ – Gwen remarks- ‘We should be out there on the floor’. ‘Maybe someday’ Mildred replies.

Ratched not only is a remarkable portrayal of a piece of queer history, it is also a captivating glimpse into the mental health system, as it allows the viewer to question the morality of many of these practices that took place. The series is set during the period of 1947-1948, shortly after the Second World War. The effect this conflict had on the mental health system was uncontested, as soldiers arrived shell-shocked and with side effects that hospitals did not know how to treat. The result was experimental and radical measures, ranging from electroshock therapy, hydrotherapy and lobotomy. Whereas the 1975 film is set in 1963, when these treatments were still in practiced but the morality was starting to be questioned, Ratched takes place at the height of these extreme therapies, when doctors like Richard Hannover were determined to instil order to the many minds in chaos.

However, it must be noted that Ratched is not meant to be an accurate portrayal of the 1940s mental health system. Some portrayals of patients are exaggerated for villainous effect (this is especially true in the case of Charlotte Wells (Sophie Okonedo, a DID patient whose alters are riotous and violent) and viewers should not expect a documentary-style approach. This blurring of fact and fiction is expertly signalled through lighting and set design. In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the hospital Nurse Ratched holds domain over is a clinical white. The walls are bereft of any decoration and the atmosphere is tense and oppressive in its simplicity. Ratched’s St Lucia Hospital is the exact opposite. The walls and surroundings are a glaring symphony of pink and white and the lobby is as luxurious as a hotel entrance. In contrast with Nurse Ratched’s attire in the 1975 film, Paulson’s Ratched is clad in a bottle green uniform and boasts an incredible range of clothing.

Ratched’s use of colour particularly stands out. When a character is angry or about to commit a crime, the entire scene is imbued in a green light. Mildred herself is also usually seen dressed in green clothing or placed next to green objects. This green is no ordinary green, but a special set of tones known as arsenic green. These pigments used to create these shades are infamous for being highly toxic and killed many people who used them for wall or dress decoration. By draping Mildred in these shades (which include Paris Green and Scheele’s Green, if anyone is interested) the series hints that she is both a toxic person but also someone who poisons herself. Much like the animal kingdom, where animals who are poisonous usually bear bright colours, Nurse Ratched openly reveals her nature through arsenic colours (for example, her car is the only one that is bottle green).

Naturally, it is impossible not to mention parallels with ‘Asylum’, Murphy’s second and widely praised second instalment of the American Horror franchise. It is funny, because Paulson almost plays a reverse role of her character in ‘Asylum’. While Lana Winters is a lesbian reporter who undergoes the terrors and tortures of Briarcliff Manor in an attempt to expose them to the public, in Ratched she is the nurse in charge of administering said tortures as she gradually questions if they are morally comfortable. Mercy is the overarching theme in Ratched, and it is up to the viewer to decide whether Mildred is an angel of mercy or a merciless devil. In an extremely entertaining interview, Louise Fletcher revealed that the key to playing Nurse Ratched was to understand that she believes that what she is doing is entirely right. She feels no qualms over what she does to her patients because it is always in their best efforts. This is why she leads a dance of death, where those who are suffering deserve to be put out of their misery. It is a complex and highly debatable theme, and Ratched’s viewers will be given plenty to question.

Finally, it is worth giving a shout-out to Ratched’s supporting characters. Judy Davis gives a highly amusing performance as Nurse Betsy Bucket, the head nurse at the hospital when Mildred arrives and who bears a painful crush on Dr Hannover. Amanda Plummer is likewise ridiculously entertaining as Louise a ‘drunken old flapper’ who is too nosy for her own good. A slightly more unusual but just as comical appearance is the inclusion of Petunia, a monkey with big Lynchian vibes owned by Leonore Osgood (Sharon Stone), an eccentric chinoiserie-obsessed millionaire who has a vengeful wish.

Overall, Ratched is an engrossing cat-and-mouse game whose colourful cast of characters, gripping storylines and exquisite costume and set design will stay in audience’s minds well after viewing. As Shakespeare affirms, mercy is ‘twice blessed’ because it grants power to those who give it and those who take it. Ratched leaves this potential of mercy in the spectators’ hands, and it is up to us to decide which of its protagonists deserve it the most.