Trigger Warning: this article makes reference to abuse, rape, FGM, misogyny, homophobia, and racism.

For some time now, it’s been known that Joss Whedon is an extremely problematic figure in the film and television industry. There’s even an entire blog dedicated to pointing out instances either in real life or in his shows and films that are not feminist. Since only 2017, his ex-wife Kai Cole released an article bringing to light his hypocrisy, his misogynistic 2006 Wonder Woman script leaked, and Ray Fisher made a statement on Twitter addressing Whedon’s “gross, abusive, [and] unprofessional” behaviour on the set of Justice League. This month, Charisma Carpenter released a statement on Twitter detailing his abusive and “casually cruel” behaviour towards her on the set of Buffy and Angel. Following this, Amber Benson, Sarah Michelle Gellar, and Michelle Trachtenberg, among other Buffy actors, have made posts either directly stating or hinting at similar behaviour they experienced from Whedon on set. Jose Molina, a writer for Firefly, later retweeted Amber Benson’s statement, adding that Whedon “thought being mean was funny”, even so far as boasting about making one writer “cry twice in one meeting”, with a specific focus on female writers.

Sadly, abusive or cruel people are rather pervasive in the film and television industry. Take the horrible way in which Stanley Kubrick treated Shelley Duvall on the set of The Shining, or Quentin Tarantino’s violent treatment of Uma Thurman in the making of Kill Bill. These examples are particularly harrowing, and involve a long-term psychological and physical impact on the women involved. Whedon’s misogynistic treatment of his female actors is a hotspot for discussion due to his renown for writing ‘strong female characters’. He has previously drawn attention to the importance of these representations of women, and the personal significance for him from his mother’s influence. As Kai Cole discusses in her 2017 article, Whedon is a “hypocrite preaching feminist ideals”:

I believed, everyone believed, that he was one of the good guys, committed to fighting for women’s rights, committed to our marriage, and to the women he worked with. But I now see how he used his relationship with me as a shield, both during and after our marriage, so no one would question his relationships with other women or scrutinize his writing as anything other than feminist.

The crux of the issue, as Cole describes here, is Whedon using the guise of feminism as a way of cloaking his actual misogyny. Especially disturbing is the fact that he cheated on his wife on the set of Buffy, further emphasising his abuse of power. Even aside from his awful behaviour towards his female actors, his works themselves reflect his misogynistic approach. In more recent times, we have his shocking portrayal of Black Widow in Avengers: Age of Ultron which received a lot of criticism. In addition to being involved in an out-of-the-blue romantic subplot with the Hulk, Black Widow compared herself to a “monster” in a conversation about her infertility. Yep, I truly have no words for how misogynistic that was. The film also included a visual gag in which the Hulk fell onto her boobs, which Whedon then went on to replicate with The Flash and Wonder Woman in Justice League two years later. Gal Gadot refused to participate, and after being reportedly threatening about it, Whedon did the scene with a stunt double instead. Sigh.

Whedon’s older works hold a notable amount of personal and cultural value, and certainly had an impact on me when I was a teenager. Hell, I’m in my third rewatch of Buffy right now! Lots of people have found empowerment and joy within the content, and the plots and characters have influenced many other films and television shows in a positive way. However, the misogyny of Whedon and outdated aspects of his works are also important to acknowledge and discuss.

Let’s look at a couple of other examples before we get to Buffy and Angel.

Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog (2008)

In 2008, Whedon released Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, which, as Sarah Z perceptively articulates, is a politically contradictory story. It follows Billy (Dr. Horrible), an aspiring supervillain, on a journey to get accepted into the Evil League of Evil. Along the way, he longs for the affections of Penny, the woman he loves, but much to his annoyance, she starts dating his arch-nemesis, Captain Hammer. There is an interesting and astute class commentary to the story, with Billy being a working class-coded character fighting a ‘heroic’ symbol for capitalism via Captain Hammer. Where Billy wants to challenge the status quo, Captain Hammer upholds it, and it’s proven time and time again that he has no sympathy for the poor (take his musical number, ‘Everyone’s a Hero’, which sums up his sentiment perfectly). Equally, any of Billy’s dubious motives or misogynistic attitudes are criticised to a certain degree by the mere fact that he is the villain of the story. It is entirely his own actions that have negative consequences for him, and we are supposed to find fault with this. However, there are still dangerous attitudes prevalent in the narrative.

The story involves an incel versus chad narrative—Sarah Z highlights this Tumblr post analysing how Billy fits the mold of “geek-flavoured” toxic masculinity specific to incels that played a role in the resurgence of white nationalism in America. He is a white male nerd who becomes obsessed with villainy due to disaffection from bullying and association with genuinely awful people. Despite his lack of romantic interactions with Penny, he feels owed a relationship with her, therefore “cuckolded” by Captain Hammer, an embodiment of traditional, idealistic masculinity. Moreover, Billy’s motivation to kill Captain Hammer stems from egotistical entitlement rather than a desire for any actual social change. Naturally, this narrative places Penny in a trophy position, a prize to be won and object of male desire. She is merely a plot device, and her death at the end is supposed to evoke sadness for Billy rather than sympathy for her. In fact, because she chooses to date the hypermasculine “chad” instead of the “nice guy”, she is essentially punished by getting killed off.

There is a level of self-awareness to Penny’s treatment within the narrative itself. At the end, we see newspaper clippings about her death that refer to her as “girlfriend of Captain Hammer” and “what’s-her-name”, directly satirising the trope of fridged women in the media. It draws attention to the way in which women’s good actions are dismissed, and how they are only ever defined through the men they date. However, Whedon is still perpetuating this by not giving her any agency in the story, and presenting her only through the perspective of male characters. We are clearly supposed to sympathise with Billy as well, as the story is a tragedy for him. I doubt it’s a coincidence that Billy reflects Whedon himself as well, as a male nerd who had experiences of bullying at high school and wants to “get the girl”, much like Xander in Buffy—but more on that later.

Firefly (2002)

Although at surface level, Whedon’s 2002 show Firefly appears to include various complex female characters, there remain to be contradictions and glaring issues of misogyny throughout. The space western follows a crew of nine renegades living on the spaceship Serenity on the fringes of society: Malcolm Reynolds (the captain), Zoë Washburne (second-in-command), Hoban Washburne (the pilot), Inara Serra (a ‘Companion’), Jayne Cobb (a mercenary), Kaylee Frye (the mechanic), Simon Tam (a surgeon), River Tam (a child prodigy), and Derrial Book (a ‘Shepherd’). From the offset, there were only two female writers across all fourteen episodes: Jane Espenson and Cheryl Cain. Then we have the issue of an American-Chinese-ruled futuristic universe with Mandarin often being spoken and a ‘fetishistic chinoiserie’ prevalent throughout the set and costume design, yet no actual Chinese or Asian characters in the main cast, let alone Chinese or Asian women. This exclusion when it comes to characters of colour is undeniable across Whedon’s shows, and I’ll get into the treatment of people of colour in Buffy later too.

The most pervasive example of misogyny in Firefly is the treatment of Inara, detailed in Amy Chinn’s essay. It is emphasised through the narrative that she has agency in her sex work, as she chooses her clients, and is considered the most respectable out of all the crew members. Despite this, she is repeatedly called a “whore” throughout the show and treated with disrespect by Shepherd Book and even Mal, which is all the more disturbing due to the romantic undertones of his relationship with Inara, made explicit in a comment by Whedon himself. In the episode ‘War Stories’, Inara is also sexualised in a scene with a female client, shown massaging and kissing her—the equivalent is never shown with her male clients, so the scene highlights lesbian fetishisation for the male gaze. An episode that thankfully didn’t make the cut was one in which Inara gets gang-raped by Reavers, who all die due to her injecting herself with a magic drug. The event finally convinces Mal to stop slut-shaming her, as he “treats her like a lady”… A lot to unpack here, but it all essentially boils down to an inherent misogyny, particularly in the treatment of sex workers.

Even in the episodes that were realised, there is a double standard in the threat of violence against male and female characters. For example, in ‘Objects in Space’, a bounty hunter invades the ship, and as Ben Ghan points out, Mal and Simon are threatened with being beaten up or shot, whereas Kaylee is specifically threatened with rape. As I will discuss later, this issue of a misogynistically-fuelled threat of sexual violence against female characters often occurs in Buffy too. When written by a man, it’s especially uncomfortable, and poses the question of whether it’s an attempt at a realistic portrayal of what women face in day-to-day life, or whether it crosses the line into gratuitous or exploitative territory. In the same vein, Jayne is consistently misogynistic in the show, and although he is called out for it by the other characters, what’s the need for it in the first place?

Other female characters in Firefly, though women in positions of authority, are still somewhat undermined or archetypal. A backstory scene reveals to us at one point that Kaylee first got the job as the ship’s mechanic because she was sleeping with the original mechanic and was able to fix the ship when he couldn’t. She is presented as a naturally gifted mechanic—so why is the reason for her position tied to both sex and a man? River is another Whedon-type supernaturally-powered woman who is literally disguised as cargo in the pilot episode, described by Simon as “more than gifted, she was a gift”. Despite her power, River is objectified and represented as a mentally unstable, vulnerable little girl to be coddled by her male counterparts. Fred Burkle’s initial introduction on Angel is very similar to this (minus the superpowers), therefore this is another narrative that shares common ground with multiple works of Whedon’s. Zoë is one of the better written female characters in Firefly, as she is second-in-command and her capability for this role is never questioned by male characters or the narrative. However, Natasha Simons acknowledges in her article that Zoë is very much “Whedon’s usual depiction of women of color: oblique, tough, and voiceless in the face of deep change”. The idea that Black women especially must be stoic, stern, and aren’t allowed to show any weakness or feel any pain is deeply problematic.

Angel (1999)

Onto the Buffyverse now, Angel being a fair bit less complicated to discuss in regards to misogyny. The very basis of the show meant that it was doomed to be less feminist, since it’s focused on a male protagonist whose course of action is usually saving damsels in distress, particularly in Season 1. There were also significantly less female writers on Angel than there were on Buffy, which was bound to have an impact, much like with Firefly. The development of certain female characters across the show is still multifaceted and compelling, but also a massive step back from Buffy, considering Whedon’s basis of that show was a feminist subversion.

The most obvious example here is Cordelia, which is even worse with the added context from Charisma Carpenter’s statement. Jenny Crusie’s essay, ‘The Assassination of Cordelia Chase’, is an excellent articulation of what went wrong with the character, but here’s an overview. Throughout the first three seasons of both Buffy and Angel, Cordelia went through wonderful character development from a seemingly vapid, judgemental, popular high-schooler to an empathetic, caring, well-rounded figure who never lost sight of her core being. Like Buffy, she was a subversive character: a dumb, vain cheerleader on the surface, but with layers of intelligence, capability, and emotional maturity. Then came Angel Season 4. After her ‘Ascension’ to become a Higher Power in the Season 3 finale (a plot twist that already didn’t align with her character), Cordelia returns in early Season 4 with amnesia that puts a wedge in her and Angel’s relationship, and instead sleeps with his son, Connor, who she helped to raise. She then becomes pregnant as a result, only for us to discover that she isn’t actually Cordelia, but has been possessed by Jasmine this whole time, a Higher-Power-turned-bad, who manipulated the characters into her own conception and is given birth to as a result. “Ew” doesn’t even begin to cover it.

Crusie discusses how Cordelia’s drawn-out possession isn’t so much a ‘Gotcha’, but rather a convoluted betrayal of her character that debases her very core. In the past, Charisma Carpenter has implied that Whedon essentially punished her for getting pregnant in real life by writing in such a gross violation of Cordelia, and her recent statement confirmed it. First of all, Carpenter couldn’t access Whedon for months to let him know about her pregnancy at his own fault. Then, when she had to work on set while pregnant, her hours weren’t reduced and she wasn’t taken care of, leading to physical exertion. The plot, character, and actor all suffered as a result of Whedon’s decisions.

Season 5 saw Cordelia remain in a coma for the first half, and then ‘wake up’ briefly in ‘You’re Welcome’. During the episode, she helps Angel and co. on a final quest, before it is revealed at the end that she had already died. After the events of Season 4, it was another kick in the teeth to tease us with Cordelia’s return only to kill her off. On top of this, Carpenter found out she wasn’t being invited back on the show via the press, and agreed to return for ‘You’re Welcome’ on the basis that Cordelia wouldn’t be killed off, to then be told after signing the contract that this would happen. Cordelia’s final episode therefore amplified the disrespectful treatment of both the character and Charisma Carpenter herself.

As for other female characters in Angel, there’s a lot to discuss as well. I’ve mentioned how Fred’s introduction on the show placed her in the role of unstable, vulnerable girl akin with River in Firefly, and she was also a damsel in distress saved by Angel, who she then reserved a crush on for her first few episodes. Once this has faded, it only made way for new issues. For the remainder of the show, Fred is placed in a love triangle with Gunn and Wesley, and even fills the role of unreciprocated love interest of Knox in Season 5. Her intelligence and capability are therefore undermined by this compulsion to give her a romantic attachment to every main male character. Additionally, she inhabits yet another Whedon archetype of the ‘cutesy nerd girl’ (other examples being Penny in Dr. Horrible, Kaylee in Firefly, and Willow in Buffy). It’s transparent of Whedon to repeatedly include this type of female character, representing a sort of fetishisation which is uncomfortable to say the least. Then, yet again, Fred is killed off towards the end of Season 5. Not only this, but her death is the result of a betrayal by Knox who is clearly bitter about her rejecting him romantically (another punishment of a female character for ‘picking the wrong guy’), and the way in which she dies involves a powerful demon god literally hollowing her out and parading around in her body for the rest of the show. Here we have another possession plot involving a violation of the female body resulting in death. So far, looking pretty bleak if you’re a woman on Angel.

Since Cordy and Fred are the only two women in Team Angel, most of the other recurring female characters are villains. First we have Darla, who is almost always sexualised and operates as a foil for Angel. When brought back from the dead by Wolfram and Hart, she immediately becomes the object of Lindsey’s affections, but with her attachment to Angel, this creates a love triangle of sorts in Season 2. Creeping into Angel’s bedroom at night and using a sleep spell on him, Darla uses sexual assault (which is never labelled as such with it being a woman perpetrating against a man—more on this with Buffy later) and dreams as a way of manipulating him. Eventually, Angel engages in hate sex with Darla in a moment of ‘perfect despair’ to further his character development, discarding her before she vanishes from the show for the rest of the season. Although her exclusion in the second half of Season 2 was due to Julie Benz’s unavailability, it still comes across as very poor treatment of her character.

Deciding what to do in Season 3, Tim Minear famously made a tasteless joke that led to Whedon’s conception of the Darla pregnancy plot: “We brought Darla back in a box, maybe we bring back something in Darla’s box” (quoted in Gross and Altman’s The Complete Uncensored, Unauthorized, Oral History of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel). As throwaway a comment as this might be, it represents how the male writers viewed their female characters—as objects or walking wombs. From this point on, Darla is defined by motherhood and finds herself ‘going soft’ as her baby’s soul is rubbing off on her, equating redemption for her with ideals of maternity and femininity. Then, during labour, she stakes herself to save her baby boy, leaving the plot to centre entirely around him and Angel. Her death serves Angel’s narrative, rendering her expendable as opposed to her male counterparts. It’s also weird that two main women (and love interests for Angel) on the show get killed off shortly after a mystical pregnancy.

Another recurring villainous woman is Lilah Morgan, a lawyer at evil corporation Wolfram and Hart. I found her to be a sympathetic character despite her villainy; she’s a woman working in the male-dominated field of law and is constantly undermined and considered inferior by her male colleagues and bosses. This is especially prevalent in her rivalry with Lindsey, who is clearly the favourite of the two. However, the narrative doesn’t give us much sympathy with her in this situation, and any excessive violence or threat against her (of which there is a fair few, a lot by Angel himself) is justified because she’s evil. At the end of Season 3, Lilah enters into a relationship with Wesley, which is one of the most interesting dynamics on the show in my opinion. However, the arc again serves Wesley’s character development more than hers, and is representative of his downwards spiral into darkness, which places her in the position of plot device. Additionally, Lilah is aware of Wesley’s feelings for Fred, and plays up to this at one point by dressing and role-playing as her during sex with him. This is unpleasant on a few levels; her pretending to be the woman he truly loves to please him is playing up to a male fantasy, and it inadvertently sexualises Fred as well, which is particularly creepy harkening back to Whedon’s nerd girl fetish. Inevitably, Lilah is killed off by a possessed Cordelia nonetheless, and has to be posthumously beheaded by Wesley to avoid her coming back as a vampire (since they think Angelus did it). While psyching himself up to do it, Wesley hallucinates Lilah and they discuss their relationship. She is presented through a man’s eyes in her final moments, removing her agency. Even when she briefly returns in the Season 4 finale, she is merely a ‘messenger’ for Angel and co. to fulfil a clause in her contract.

Like Lilah, we are introduced to another Wolfram and Hart employee in Season 5, Eve. Team Angel treats her with suspicion, which is natural considering she works for an evil law firm; however, it plays into a similar justification of maltreatment that we had with Lilah, plus Eve insists she is genuinely there to help Angel. In ‘Life of the Party’, Lorne’s psychic influence causes Eve and Angel to have sex, which is unnecessary and non-consensual. It buys into the idea that Angel being distrusting and aggressive towards Eve is synonymous with a kind of desirable sexual tension, and the narrative plays off what is a sexual assault of both characters for laughs. At the end of ‘Lineage’, it’s revealed that Eve is in fact evil (further justifying any poor treatment of her), and not only working with, but sleeping with Lindsey. This completely undermines her role in the season, and she gets immediately sidetracked because of Lindsey taking up the gauntlet of a more primary villain. After this, Eve is forced to sign away her immortality by Marcus Hamilton, further diminishing her power. The last we see of her is standing in the crumbling offices of Wolfram and Hart, asking where she should go, which again emphasises her lack of autonomy and independence.

Frequent recurring character, Harmony Kendall, also becomes an employee of Wolfram and Hart in Season 5… as a secretary. She is repeatedly portrayed as a ‘dumb blonde’ (as is her role in Buffy too), and jokes within this realm are made at her expense throughout the season. ‘Harm’s Way’ gives her a central role and credit for being more capable than people assume, but this message is undercut by the general treatment of her and other women, especially in Season 5. Harmony is also often attached to relationships with men—the moment Spike becomes corporeal again, he goes to have sex with her again, which is regressive for her character considering he was abusive to her in Season 4 of Buffy and she supposedly got past that. Akin with Eve, Harmony is also revealed to be evil in the end as we find out she’s been sleeping with Hamilton, another instance of getting sidelined by a prominent male villain via a sexual relationship. She betrays Angel and doesn’t even get to be part of the final battle since she flees, leaving a farewell letter to Angel and Hamilton that says “May the best man win”. This is further proof that Angel, particularly Season 5, is a boys’ game.

On that note, it’s important to point out that by the end of the show, there are no surviving or remaining women in the cast other than Illyria, whose gender is ambiguous anyway; they are all either killed off or made to vanish. Even Nina, a werewolf lady introduced in Season 5 who becomes Angel’s girlfriend, simply gets sent away by Angel for protection reasons before the final battle. It’s almost like women are disposable or non-integral to the story…

Aside from this rather shocking treatment of its female characters, there are a couple of Angel episodes that attempt to directly deal with feminist issues, but they fall short. First is Season 1’s ‘She’, written by Marti Noxon. The episode has a central FGM (female genital mutilation) metaphor in the form of a race of demons. The females of the species have their personality, desires, passions, and overall physical and sexual power located in an area of their body called the “ko”, which the male demons cut out in order to maintain control over them. Sadly, the commentary falls flat since Jhiera, the main demon woman, is placed in a romantic subplot with Angel. Both characters are shown to be sexually aroused by one another, which undermines any serious commentary on the issue at hand. Furthermore, Angel asserts at the end that he’ll stop Jhiera if she causes any more collateral damage as a result of trying to protect her people, which she agrees to. Even in a feminist commentary, the main woman’s power is capped by the male protagonist.

Another episode is Season 3’s ‘Billy’, written by Tim Minear and Jeffrey Bell. It actively addresses the topic of misogyny but in a heavy-handed and misinformed way. A demonic man, the eponymous Billy, causes other men to become violently misogynistic with a mere touch, including Wesley. The use of misogynistic register and slurs against Fred feel excessive, and she is placed in the position of having to comfort and reassure Wesley at the end of the episode, despite having been attacked by him. Additionally, the episode implies that Billy doesn’t make men misogynists, but actually brings out a primal misogyny in them. This is a reductive perspective of the issue that completely eradicates the social and cultural cause of misogyny, and also incidentally removes responsibility from men by assuming they have no control over a misogyny that is inherent within them.

There was some real potential with Angel‘s female characters (especially Cordelia) and attempt at feminist commentary. The range of women from the unassuming Fred who is incredibly intelligent and eventually a physical fighter, to morally fluid and layered Lilah and Darla, has merit to it. But ultimately, women are second to their male counterparts in the show, and the underlying misogyny and abuse of Charisma Carpenter undercuts the successes.

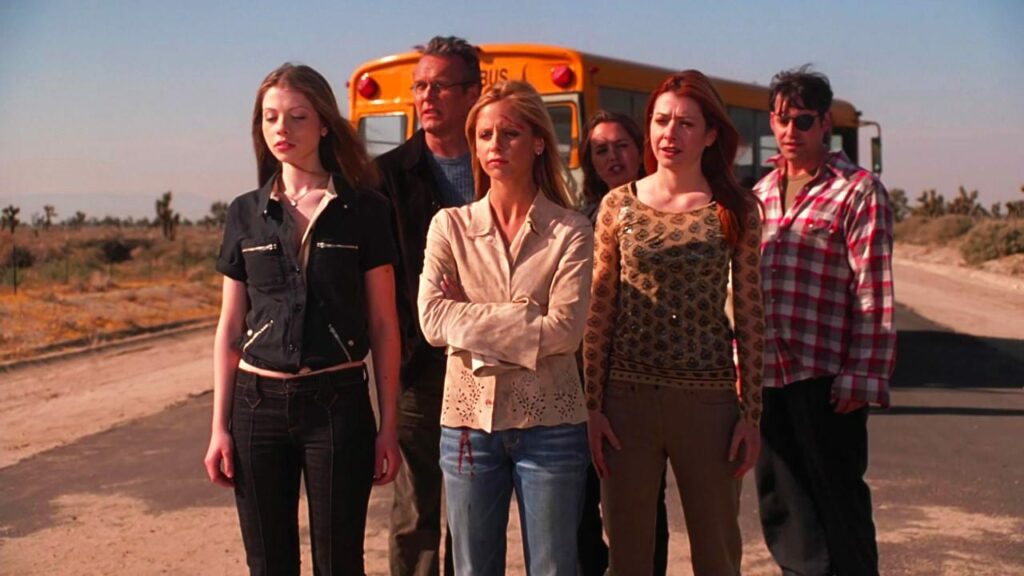

Buffy (1997)

Of all Whedon’s works, Buffy the Vampire Slayer is the one heralded as feminist media, which in many ways it is. The female characters in Buffy are generally well-written, three-dimensional, complex women. Aside from the foundation of the show being a feminist subversion, Buffy herself is strong and realistically vulnerable, silly and intelligent, funny and hard-working. The women in the show all have drive and power, whereas the men usually don’t, and exist purely to serve Buffy and other women. These are all positive, influential feminist aspects of the show. However, on closer inspection, perhaps Buffy isn’t actually as feminist as it appears. As well as it being outdated in a few ways now, Whedon’s misogyny still seeps into Buffy in various ways.

Let’s start with Xander. Marina Watanabe’s article, ‘The Quiet Misogyny of Buffy the Vampire Slayer‘, brilliantly details the deep-rooted misogyny surrounding his character; she posits him as the wisecracking, nerdy “nice guy” (akin to Billy from Dr. Horrible) whose actions and attitudes are repeatedly upheld as “morally correct” when he is clearly in the wrong. In the first season of Buffy, Xander has an unrequited crush on Buffy, and even after he seemingly gets over this, he withholds a possessive entitlement of her. He harbours resentment towards every guy Buffy dates (especially Angel) and lashes out at her quite sorely when she rejects him in the Season 1 finale. Furthermore, Xander makes creepy, sexualising comments towards multiple other women in the show, particularly the other Slayers, which is an obvious projection of his feelings for Buffy. Not forgetting the part in ‘Restless’ where Xander makes an allegorical reference to masturbating over Willow and Tara, and dreams that the couple, dressed in dominatrix-style outfits, invite him for a threesome. Including such a blatant lesbian fetishisation was Whedon’s choice, and undercuts the progressiveness of Willow and Tara’s relationship.

This undeniable aspect of Xander’s character is even more problematic considering he is a literal Whedon self-insert. Therefore, Xander’s misogynistic behaviour emulates Whedon’s own attitudes. Watanabe points out the irony of Whedon aligning himself with the most powerless character in the show while abusing his actual position of power on set. In his previously cited Equality Now speech, Whedon claims his intention was to “surround [Buffy] with men who not only had no problem with the idea of a female leader, but, were in fact, engaged and even attracted to the idea”, before going on to joke that he writes characters like Buffy “cause they’re hot”. This unveils Whedon’s ‘feminist’ motivation as performative; he doesn’t actually respect strong women, but instead finds them sexually appealing. Moreover, Whedon’s self-projection onto Xander, a character who has feelings for Buffy, reflects his sexualisation of her. The mere fact that Whedon has a tendency to write these ‘strong women’ archetypes denotes a kind of fetishisation of them, much like his ‘nerd girl’ type. The further inclusion of Xander somehow always having women attracted to him shows he is vicarious for Whedon, but especially uncomfortable is Dawn’s crush on Xander. In Michelle Trachtenberg’s statement against Whedon, she said that “there was a rule saying he’s not allowed in a room alone with [her] again”, which has a further disturbing implication concerning his abuse of power.

Another way in which Whedon undermines Buffy is via the misogyny of male villains, which is yet another recurring trope across various Whedon works. Most of the male villains—generic vampires, the Master, Dracula, Spike, etc.—use misogynistic or sexually threatening language when interacting with Buffy. In ‘Prophecy Girl’, the Master says, “I’m waiting for you. I want this moment to last”, and when Buffy replies, “I don’t”, he drinks from her regardless. Similarly, in ‘Buffy vs. Dracula’, Dracula tells Buffy, “I have searched the world for you. I have yearned for you”, and when he drinks from her, he dismisses her “No” with “Do not fight”. Both examples involve language and actions that emulate sexual assault. Additionally, male villains often call Buffy a ‘bitch’, ‘little girl’, or even ‘whore’ in some cases, degrading her in a specifically misogynistic manner. Arc villains such as Warren and Caleb are textually explicit misogynists who enact targeted violence against women. In fact, the Trio as Season 6’s primary antagonists are a surprisingly astute commentary on the correlation between toxic ‘nerd’ masculinity and sexual assault or murder of women. However, Whedon had less creative control at this point with Marti Noxon taking over as showrunner, and the commentary is slightly nullified by the obvious sympathy we’re supposed to have with Xander who is the same type of character.

There is something to be said for the idea that male villains would be threatened by Buffy’s power and attempt to undermine her in this way; however, why is it necessary to see Buffy repeatedly degraded in terms of her womanhood? Mary Magoulick’s essay, ‘Frustrating Female Heroism: Mixed Messages in Xena, Nikita, and Buffy’, addresses how, instead of demonstrating women’s equality, the show actually reveals the opposite via Buffy’s fights with male villains. They project anger towards strong women, inadvertently upholding the idea that women can’t be warriors or powerful figures without meeting the opposing force of misogyny at every turn. Perhaps it would have actually been more feminist to witness Buffy being the hero without constant sexism weighing in on every fight.

A key character study related to this discussion of misogynistic male villains is Spike. He often uses pet names when interacting with Buffy, such as ‘love’ or ‘kitty’, another example of diminishing her power by being condescending. Sexual innuendo plays a significant part of his conversations with Buffy too, and his ever-present conflation of love, sex, and violence ties into this portrayal of him as a sexual predator. In spite of this, Spike is an obviously charismatic character who we are supposed to find sexy, charming, and entertaining. Season 6 sees a shift in his dynamic with Buffy, as they enter into an abusive, toxic, sexual relationship. Though some writers have stated this relationship was supposed to be perceived as unhealthy and bad, others have condoned their romance, and many fans still shipped Spuffy throughout the season, proving that the distinction wasn’t made clear. Spike’s attempted rape of Buffy later in Season 6 crossed the line into that distinction. In the aftermath of this, the only person who labels it as ‘rape’ is Xander, whereas Buffy herself deflects and even defends Spike. Then, Spike retrieving his soul is considered the appropriate redemption for what he did. Even more so, Season 7 has Buffy repeatedly placed in the position of comforting Spike and reassuring him that the attempted rape was not his fault. This is, quite frankly, a disgusting way of framing such a narrative. It places more sympathy on Spike, a misogynist and attempted rapist, than Buffy herself, the survivor.

Aside from Spike, who is the most extreme example, none of Buffy’s relationships or boyfriends are healthy or good for her. Her early relationship with Angel is romanticised to the highest degree when he is a 240+ year old vampire dating a 16 year old girl; even in human years, he’s 26, according to his gravestone in the Angel episode ‘The Prodigal’, which is especially creepy. Angel losing his soul as a result of Buffy losing her virginity to him is essentially a punishment of Buffy too, which is a very conservative and misogynistic perspective of sex. It’s not the only instance of this either; sex often has negative, even catastrophic consequences for her and others. In ‘The Harsh Light of Day’, Buffy faces negative consequences of a one-night stand with Parker, as he does the typical thing of not calling her back and claiming it was just ‘fun’. She blames herself for this, and is also slut-shamed by Spike in one fell swoop. Then, in ‘Where the Wild Things Are’, Buffy’s relentless sex with Riley makes her unavailable to help her friends when the frat house is being attacked by demonic spirits. As a boyfriend, Riley suffers from toxic masculinity-fuelled insecurity which we are expected to empathise with him for, even though it has an impact on Buffy. He even accuses her of cheating on him multiple times (with Angel and Dracula), despite her showing him nothing but love and care throughout their relationship. It draws on the idea of a woman ‘making’ a guy act ‘crazy’ out of love, and even after Riley has cheated on her with a nest of vampires (that irony isn’t lost on me), the blame and responsibility is placed on her to make him stay. By Xander, of course.

Angel and Spike also tie into the concept of dangerous yet attractive men who are presented as the romantic ideal for women. This ‘bad boy’ media archetype is a desirable figure that women are supposed to aspire to be with, or to ‘fix’. The problematic concept isn’t unique to Buffy, as it’s consistent across most media whose target audience is teenage girls. Attention is also drawn to Buffy’s attraction to dangerous men who cause her pain, so we’re aware this is unhealthy. However, her relationships are still presented as sexy or desirable for a female audience.

On the other side of the coin is sexualised female villains. The women in the show who express an enjoyment of sex for their own pleasure in a direct way are either villains, ex-villains, or to-be-villains. Buffy, and other main female characters such as Willow, do have sex, but are either punished for it (as mentioned), or simply don’t discuss it often. Darla and Drusilla are often sexualised or speak in a flirtatious manner, Vampire!Willow is dressed in head-to-toe leather and acts sexual, Faith is open about her enjoyment of sex and dresses in leather and dark makeup, and Anya (an ex-demon despite being one of the good guys) is frequently reprimanded for talking openly about sex, and also ostracised by Buffy and Willow. There is a distinct difference between Buffy and Willow, the ‘good girls’, and these female characters demonised by the narrative for enjoying sex. In fact, Buffy and Willow often refer to Faith as “slutty”, and any fights between Buffy and female villains usually involve quips about hair or fashion sense. This internalised misogyny is very much a product of the time when the show aired, but it’s played straight and is often coming from a male writer’s perspective.

Flagging up Faith here, she’s an important character in this discussion of sexualisation. Eliza Dushku was a minor when she first arrived on the show, therefore her portrayal in this way, plus Xander’s objectification of her, is particularly creepy. However, a more glaring issue is the fact that Faith sexually assaults various male characters, with no proper identification of the event as such within the narrative. She sexually assaults Xander in ‘Consequences’, and rapes Riley in ‘Who Are You’ via a body swap spell with Buffy. No attention is placed on Xander’s experience in the former, and Buffy actually addresses Riley with an accusatory tone in the aftermath of the latter. Ignoring instances of male rape or sexual assault when perpetrated by a woman goes against feminist values.

A significant controversy at the time Buffy aired (and still is to this day) was Whedon killing off Tara. Up until that point, Willow and Tara (apart from the previously mentioned sexualisation) were a beautifully nuanced portrayal of queer women and a lesbian relationship. It was genuinely progressive at the time, since on-screen LGBT+ characters were extremely rare. Of all the relationships in the show, Willow and Tara’s was also one of the healthiest, being framed in such a way that connoted deep love, peace and self-confidence. This was why fans felt so betrayed when Tara was killed off.

Of course, many characters got killed off throughout the show, which was Whedon’s main justification, but this particular death had certain implications that could have been handled better. As well as playing into the homophobic ‘bury your gays’ trope, the event saw Tara die immediately after getting back with Willow and having sex with her, at the hands of Warren, a misogynistic killer. This chronology implies another punishment for sex, specifically lesbian sex, perpetuating the idea that LGBT+ people can never have a happy ending. It’s bad enough that Buffy faces misogyny in her everyday battles, but having Tara actually be murdered by a dangerous misogynist is even more salt in the wound. The way it comes across shows a lack of perspective on the matter, which is why it faced such backlash, from queer women especially. Marti Noxon, the showrunner for Season 6 and 7, later admitted that she regretted the decision to kill off Tara.

Lacking in perspective or good representation is also the narrative of people of colour, especially women of colour, in Buffy. Ewan Kirkland’s essay, ‘The Caucasian Persuasion of Buffy the Vampire Slayer’, acknowledges how characters of colour on Buffy were few and far between, and those that were included were heavily stereotyped or mistreated. Featuring an over-the-top Jamaican accent that was mocked by Buffy, Kendra was introduced as the second Slayer in Season 2, only to get killed off after three episodes. Mr Trick becomes a recurring villain in Season 3, but is second to the Mayor, and killed off just over halfway through the season. Even a Sunnydale High counsellor, Stephen Platt, was introduced and killed off in the same episode. This tendency to quickly kill off Black characters in the early seasons of the show is a revealing trope for the expendability of characters of colour.

Season 4 brought us two more Black characters: Olivia Williams, Giles’ girlfriend, and Forrest Gates, Riley’s best friend and fellow Initiative soldier. Olivia is in a total of three episodes, essentially as a sidekick to Giles, before disappearing entirely. Forrest is consistently portrayed as nasty and aggressive towards Buffy, killed off, and then turned into a demon-hybrid before getting killed off a second time. Again, these Black characters are either insignificant to the plot, or stereotyped and killed without much thought. Also in Season 4 is ‘Pangs’, a Thanksgiving episode involving a central conflict with Chumash Native American spirits. In the conversation had about Thanksgiving, the injustice inflicted upon the Chumash is vocalised through Willow, which Kirkland describes as “a typical display of white guilt”. At the end of the day, the Native American spirits are just a monster of the week, and portrayed as one-dimensional evil. Yikes.

Along with Kendra, most other representations of non-white women in Buffy are Slayers. In ‘Fool for Love’, we see two previous Slayers who aren’t white: the Chinese Slayer (unnamed) and Nikki Wood, a Black woman. Spike killed them both, and recounts the stories of this for Buffy to further her understanding of Slayerdom. These Slayers are shown to be ultimately weak for one reason or another, and only function to serve Buffy’s progression. In Season 7, Nikki’s son Robin Wood becomes a recurring character. He’s a vampire hunter who vowed to kill the vampire that killed his mother, which, said vampire being Spike, creates a conflict. Even though Robin is objectively justified, the narrative sides with Spike yet again, therefore antagonising Robin. After Spike spares Robin out of ‘respect’ for Nikki (which is honestly just patronising), Buffy says she will let Spike kill him if he attempts to harm him again. This is extremely disrespectful and serves to uphold Spike, a white misogynist. Another character of colour in Season 7 is Chao-Ahn, a Chinese Potential Slayer. She doesn’t speak English, therefore has basically no agency; her voice is filtered through Giles’ broken and inaccurate translations.

One of the most racist portrayals of a Black character is the First Slayer. We first see her in ‘Restless’, where she is initially presented to us as the villain. She is described as a “primal” force, “destruction absolute”, and moves in an animalistic way. At various points, Buffy taunts her by targeting her hair specifically, even saying “in terms of hair care, you really wanna say, what kind of impression am I making in the workplace?”. This implication that Black hair is ‘unprofessional’, especially by our white protagonist, is deeply racist. Xander and Willow also collectively claim the First Slayer is “not big with the socialisation” “or the floss”, further adding to the idea that this Black woman is incompatible with their white perspective of what’s acceptable in society. Feminism is not feminism unless it’s intersectional, and even though these representations of non-white characters are obviously outdated now, it’s still a deep-rooted issue.

Buffy was progressive and feminist in many ways; its range of complex female characters, breakthrough representation of a lesbian relationship, and all-round empowering message should not be taken away from it. The show had a huge cultural impact on feminist media and representation of female leads in television and film. However, the suffering of female actors on set, and the still-existent inclusion of misogyny in the show, projected by Whedon’s own attitudes towards women, should be acknowledged. The empowerment and enjoyment that us fans get from Buffy isn’t to be taken lightly, but we need to separate this from the actual negative experience of actors on set, and from Whedon himself. Also, with television being a collaborative process, many other writers and creators were involved in Buffy and Whedon’s other works. He is not 100% responsible for every decision or aspect of the show, and it would be a disservice to the actors and other writers—especially women who have suffered because of him—to give him all the credit. As Sarah Michelle Gellar said herself, she is proud to be affiliated with Buffy Summers, but not Joss Whedon. The positive content and feelings that the show has given its audience can exist outside of his association, and we can reclaim that.