Content Warning: This article makes reference to rape, sexual assault, misogyny, blood, capital punishment, and family death.

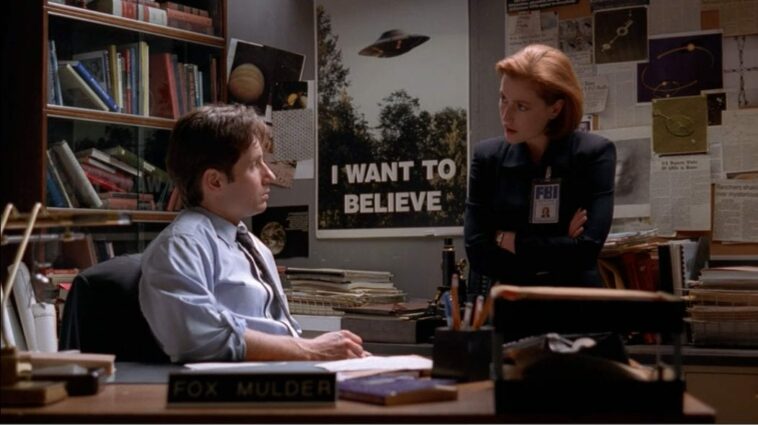

Everyone who knows about The X-Files, often even if they haven’t watched the show, is aware of the roles that Mulder and Scully inhabit: believer and sceptic respectively. It’s the core identity of both characters, and is drilled into the viewers from the very first episode. Apparently Chris Carter, the creator of the show, intentionally flipped gender roles by crafting this celebrated aspect of The X-Files. Being a believer relies on faith and intuition, whereas scepticism relies on a scientific, logical mindset; the former is often aligned with stereotypical femininity, and the latter with stereotypical masculinity. There are, of course, issues with how Scully is handled (to put it lightly), particular portrayals linking to gender, and even inconsistencies with the believer/sceptic roles. With this basis, let’s take a deeper dive into Mulder and Scully’s characters and how this manifests throughout the show.

Mulder’s role involves an incredibly strong belief in alien life and the paranormal, to the point where he’s blinded by it. He’s often far more trusting of sources than he should be, which results in him being consistently betrayed and let down by people seeking to take advantage of his weakness. Of course, Mulder doesn’t see his willingness to believe as a weakness—he almost sees it as common sense. Mulder’s main personality traits are empathy, enthusiasm, intuition, and impulsivity, all of which frequently culminate in an intense obsession. Working off a basis of emotion and instinct is a trait commonly associated with women, yet is central to Mulder’s character. However, his heightened emotional state occasionally spirals into angry outbursts, such as when he lashes out by kicking a bin in ‘Bad Blood’ (though done for comedic effect here). This is a display more often seen in male characters, although it isn’t as prominent as his instinctive nature.

In contrast, Scully has quite the opposite approach. Her role as the sceptic involves constant attempts to debunk Mulder’s seemingly wacky theories, and general reluctance to consider anything beyond the scientific. Scully’s main personality traits are remaining rational, logical, conventionally professional (by initially adhering to orders and rules from superiors), and strong-willed to the point of obstinance. Her affiliation with science is a stereotypically masculine trait, as is her emotional control and repression. Despite this, Scully does have a sensitive and vulnerable side, and is supportive of Mulder and other characters in what could be construed as an almost nurturing, maternal way.

A good example which clearly shows Mulder and Scully’s respective roles as the believer and the sceptic is the Season 3 episode ‘Oubliette’. In this, a woman named Lucy shares a psychic connection with a girl called Amy because they were both kidnapped by the same man at different times. Lucy gets the same wounds as Amy does when she is hurt by her kidnapper, and actually bleeds Amy’s blood; blood tests show that the blood on Lucy is Amy’s blood type, not Lucy’s. Seeing the scientific evidence in front of her, Scully thinks that Lucy is the perpetrator, and is set on arresting her for the majority of the episode. Mulder, on the other hand, goes with his instinct and firmly believes Lucy is innocent due to some unseen link that is physically connecting her with Amy. The two agents have such wildly opposing perspectives to balance each other out; this contrasting characterisation was created so that the events of the show aren’t just viewed from one angle.

However, a consistent issue with The X-Files in spite of the purposeful gender role subversion is the narrative siding with Mulder. In their book Hollywood Divas, Indie Queens, and TV Heroines, Susanne Kord and Elisabeth Krimmer make an excellent point in regards to this problem:

Paradoxically, it is the oft-celebrated gender reversal at the heart of the series that detracts most from its feminist potential. […] [I]n the world of The X-Files, a series that takes delight in unexplained phenomena and supernatural occurrences, science is usually wrong; meanwhile Mulder’s instincts, supported by his immense knowledge ranging from physics to the history of the occult, are generally proven right.

What this is essentially saying is that, despite Scully’s intelligence, logic, and scientific mindset in blatant (and commendable) defiance of gender roles, the narrative repeatedly validates Mulder’s perspective—therefore bringing a simultaneous confirmation that Scully is wrong, uninformed, or even stupid. Sure, after you’ve been presented with physical evidence of the existence of aliens and other supernatural phenomena multiple times, then it’s on you if you choose not to accept it. But Scully isn’t an autonomous figure, she’s a fictional invention written to have those opinions. Choosing to represent her in a way that makes her look foolish is detrimental, undermining the feminist (or at the very least, subversive) foundation of her character.

Since Mulder is the driving force behind the plot, this also puts Scully in the position of “supporting his mission”. Kord and Krimmer further posit that she is “a sounding board for Mulder’s flights of genius”. Although Scully is shown time and time again to have in-depth scientific and academic knowledge, this is partially undercut by Mulder being presented as some kind of adult prodigy. He has rich academic knowledge on a multitude of topics almost surpassing Scully, which is also coupled with impromptu eureka moments that nearly always turn out to be spot-on.

Sadly, there are many more issues in the show’s treatment of Scully and women in general—it would take a whole other article to cover that, so I won’t go into much detail. As A.J. Black mentions in his article on Season 6 and the MSR, there are instances of comedy generated from Scully being sexually assaulted, she’s pitted against other women that are introduced as past or present love interests for Mulder, and is portrayed as bitter, jealous, and resentful of these women in a way that to me emulates internalised misogyny. Taking into consideration the fact that there is a significant lack of female writers and directors across all seasons of The X-Files which Gillian Anderson herself has spoken out about, it comes across as a heavily male-centric, disappointing representation of women.

This aside, there are also some intentional inconsistencies with Mulder and Scully’s characterisation as believer and sceptic. In some episodes, these roles are entirely switched. In ‘Beyond the Sea’ (S1E13), a supposedly psychic prisoner on death row (Luther Lee Boggs) is used to help solve a kidnapping case. Mulder kicks off the theme of reversed roles by saying: “I believe in psychic ability, without a doubt, but not in this case.” He repeatedly insists that Boggs is in on the crime by being in cahoots with the actual perpetrator, Lucas Henry, and that’s how he knows where the evidence will be. On the other hand, Scully starts off the episode feeling vulnerable from her father’s recent passing. When Boggs sings the song played at her father’s funeral, and refers to her by a nickname only her father called her, Scully is shaken and so is her usual sceptical resolve.

She starts to believe in Boggs’ psychic abilities, which are backed up by the things he says consistently coming true throughout the case. Unusually, Mulder doubts her and has to try to convince her that Boggs is faking the clairvoyance. For the most part, Scully’s apparent belief is framed as an expression of her personal grief and troubled mindset in the wake of her father’s death, as opposed to Mulder’s usual genius intuition when in that position. However, we see the evidence and Boggs’ POV of truly seeing ghosts on his way to execution, so Scully is supported by the narrative. At the end of the episode, though, she attempts to rationalise what she’s witnessed; Mulder once again (albeit quite suddenly) returns to the role of questioning “why can’t you believe?”.

A similar progression is seen in ‘Excelsis Dei’ (S2E11). Michelle Charters, a woman working in a nursing home, is raped by an invisible entity, and multiple staff and patients are later murdered by the same unseen force. Mulder addresses that there are other similar cases, but he doesn’t believe that the women were attacked by ghosts. He even goes so far as to question the credibility of Michelle’s statement, implying that she “concocted this story to get out of a job she hates”. Scully, however, believes Michelle, shows compassion towards her, and defends her against Mulder’s invalidating claims by pointing out that there’s no way she could have invented her severe injuries.

After Scully suggests that the building itself could be the issue (due to fungus in the walls, but Mulder assumes she means that it’s haunted), Mulder smirks and replies, “I think you’ve been working with me for too long, Scully.” He’s almost mocking her, and drawing direct attention to their usual roles being switched here. It’s revealed that mushrooms are in fact being grown in the building, and being fed to patients to cause hallucinations. Here is where the split between Mulder and Scully’s opinions reverts back to normal. Scully believes that the mushrooms are causing violent behaviour in the patients that led to the attacks and murders, whereas Mulder thinks they’re allowing the patients to see the dead and unleashing an angry spirit in the process. Towards the end of the episode, Mulder witnesses Michelle getting attacked by spirits first-hand, and is trapped in the bathroom with her, putting him in the position of fully supporting her.

It feels like a deliberate choice for the writers to put Scully in the shoes of the believer in regards to a case involving a woman being sexually assaulted. Unfortunately, Mulder is then the mouthpiece for invalidating survivors, which is unpleasant to watch. The misalignment with his usual belief of supernatural activity makes his objectionable argument stand out all the more. Almost immediately after Mulder and Scully interview Michelle, her character is sidelined for the rest of the episode, so the attention shifts from her specific story onto a more general case of strange happenings. This shift then leads more naturally into Mulder and Scully settling back into their respective roles, but it does a disservice to the initial angle.

In relation to the topic of co-opting each other’s perspectives or basic traits, a particular scene from ‘Clyde Bruckman’s Final Repose’ (S3E4) sticks out like a sore thumb. Towards the end of solving the case, Mulder is chatting to another agent when Scully aptly notices a piece of evidence and says “It’s the bellhop. He’s the killer, the bellhop at the hotel!” When the other agent asks how she knew, Mulder replies, “Woman’s intuition”. This comes across as very hypocritical on Mulder’s part, since he’s known for running on intuition. Why, then, is it suddenly labelled as ‘women’s intuition’ when Scully uses hers? Perhaps the show is purposely drawing attention to its reversal of gender roles by overtly attaching a gender stereotype to the trait.

When the writers decide to throw in a curveball by shaking up Mulder and Scully’s believing or sceptical approaches to a case, it seems to be for the purpose of the plot. It makes their characters more complex, knowing they each contain within them the capacity for the juxtaposing perspective. However, it can still be rushed and inconsistent, and it ultimately serves the narrative above all. Their roles need to be opposite to give balance to the show. In the end, they inevitably return to their established status quo.

Another aspect of Mulder and Scully’s personal credences is their respective approaches to religion. Reinforced by her gold cross necklace, Scully is Catholic (though not always practising). This showcases a side of her that does believe in something unseen and unproven, just like how Mulder believes in the paranormal. Furthermore, this trait of having faith in the intangible is more closely associated with women. I think being Catholic is a particularly compelling facet of Scully; she is firmly scientific and requires solid proof of the paranormal, yet has enough faith to believe in a higher power despite a lack of evidence. This appears to be quite a contradiction, but in fact it contributes to the complexity of Scully’s character. Yes, she’s a scientist and incredibly logical-minded, but that doesn’t mean she can’t be religious too. Science and religion aren’t mutually exclusive, and Scully represents this composed duality of logic and faith.

On the other hand, Mulder has quite a different approach to religion, and this causes some dispute between him and Scully at various times throughout the show. It’s essentially the reverse of Mulder’s belief and Scully’s scepticism concerning alien life. Then again, the two characters are given opposing viewpoints to balance each other out, so it’s no surprise that this occurs with their religious views as well. However, Mulder doesn’t outright reject religion or the possibility of God’s existence; his faith is, in fact, ambiguous. He often labels supposed faith healers or miracles as ‘fakes’, although he has been shown taking refuge in Christian churches. There are numerous hints throughout The X-Files that Mulder is Jewish, and David Duchovny himself has suggested this in an interview (according to The Official Guide to the X-Files Volume 1). Despite this, Mulder is rather detached from religion and doesn’t have as much of a personal experience of it as Scully does.

An example of Mulder’s scepticism and Scully’s faith concerning seemingly religious events is in ‘Revelations’ (S3E11). The episode starts with a reverend faking crucifixion wounds before getting killed, but a child called Kevin starts to exhibit real wounds of the same kind shortly afterwards. Owen, a man claiming to be Kevin’s “guardian angel”, reprimands Scully for going through the superficial motions of her faith such as eating fish on Fridays, but not being a true Christian due to questioning God’s word. In the opposite way, Mulder tests Scully’s faith by refuting her religious references to the case, specifically when Owen’s body won’t decompose and she mentions ‘incorruptibles’ from the Catechism. Mulder disregards her belief in miracles, claiming that saints don’t exist and that she’s letting her faith overwhelm her judgement. In actuality, faith is aiding Scully’s judgement by allowing her to analyse the events in more detail. It even enables her to find the killer and Kevin at the recycling plant at the end, saving the boy’s life. Her relationship to Kevin becomes rather maternal as the episode progresses—this creates a link between faith, or intuition, and stereotypical femininity.

The idea that “we must come full circle to find the truth” recurs throughout ‘Revelations’. Kevin’s father initially mentions the phrase which later leads Scully to the killer and Kevin, but the phrase is repeated again by the priest in the confessional booth at the end. During her confession, Scully admits that she hasn’t been to confession in six years and that she’s “drifted away from the Church”. This suggests that she was previously faithful to her religion, then perhaps got more involved in science with her medical studies and career. In order to “come full circle”, Scully has now become more involved in her faith once again due to her experience on the case. This shows a deeply intriguing character complexity, especially considering the excessive development focused on Scully in a single episode. It also confronts the conversation regarding the interplay between science and religion head-on.

Scully directly questions Mulder’s hypocrisy regarding his polarising approaches to the supernatural and religion in the episode:

How is it that you’re able to go out on a limb whenever you see a light in the sky, but you’re unwilling to accept the possibility of a miracle? Even when it’s right in front of you.

Mulder claims that he “wait[s] for a miracle every day”, but that this case has only tested his patience, not his faith. It’s a key distinction to make between the two characters. Mulder tends not to believe when the topic is something that he feels is an inconvenience and hindrance to a case. Scully’s scepticism dissipates as a result of the evidence being of personal significance to her, such as her grief in ‘Beyond the Sea’, sexual violence against women in ‘Excelsis Dei’, and Christianity in ‘Revelations’. These instances, all occurring in Scully-centric episodes, delve into a more empathetic understanding of her.

‘Believer’ and ‘sceptic’ feel like obstinate roles, and are set up as such from the start of The X-Files. Though there are occasionally somewhat far-fetched reversals of these roles, the topics and conversations addressed via pushing the boat out with Mulder and Scully’s characterisation are extremely thought-provoking. It’s certainly not the best representation of gender, far from it, but the show’s influence on gender role portrayal in subsequent media is undeniable. If you look at almost any leading male and female characters in cop shows since The X-Files came out (Bones, The Mentalist, Castle, to name a few), Mulder and Scully are very much present—the whimsical, eccentric, intuitive man as a counterpart to the stoic, logical, scientific woman. Plus, it still warms my heart to this day that Scully’s character inspired a generation of young women to pursue STEM careers.