Many won’t make it far beyond the opening scream of The Great Southern Trendkill. Still, those who endure, let alone enjoy that ear drum eradicating intro will never be the same. It opens with a primal cry which seems defiant, but as the record progresses, songs reveal a terrible sadness beneath the rage. A lyrical vivisection ensues from start to finish, and though ferocious instruments make it a thrill, what’s heard is exactly why heavy metal possesses an underappreciated depth.

Even after 25 years, the album is a merciless display of metal combining several genres into one epic record. However, it contains moments of brutal honesty that border on a strange softness. As such, Pantera’s The Great Southern Trendkill is an intensely affecting album—the musical equivalent of a meat hook that gives a listener the means to rip open others as well as themselves. Not to mention a way, albeit grim, of holding up when falling down seems the only option—impaled and hoisted off the killing floor.

I didn’t grow up in a house that welcomed the hard stuff. Although my father enjoyed Elvis, he drew the line at any rock ‘n’ roll after The King. He often subjected me to documentaries like Geraldo Rivera’s Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground. Satanic panic junk food depicting “metalheads as blood drinking, graverobbing, sacrilegious hooligans.” Heavy metal didn’t factor into my parents’ vision of my future, especially Mom who, on her death bed, wanted me to be Pope. They never understood the allure of this atavistic, aggressive music. To be honest, neither did I at first, partly because that meant admitting things about myself I didn’t want to.

Metal is a genre for people who never felt powerful. Those who grew up outcast, without hope, and angry. It’s a sound-path to confidence and self-respect as well as the sonic key to the land of misfits. Beloved bands weave loners into a legion, sometimes connected across borders. I don’t speak Japanese, but someone from Tokyo singing Pantera shares a common tongue.

“Step aside for the Cowboys from Hell!”

Dave Mustaine once said, “If Elvis Presley released the body and Bob Dylan released the mind, we’re releasing whatever’s left: all the stuff that people would rather overlook.”

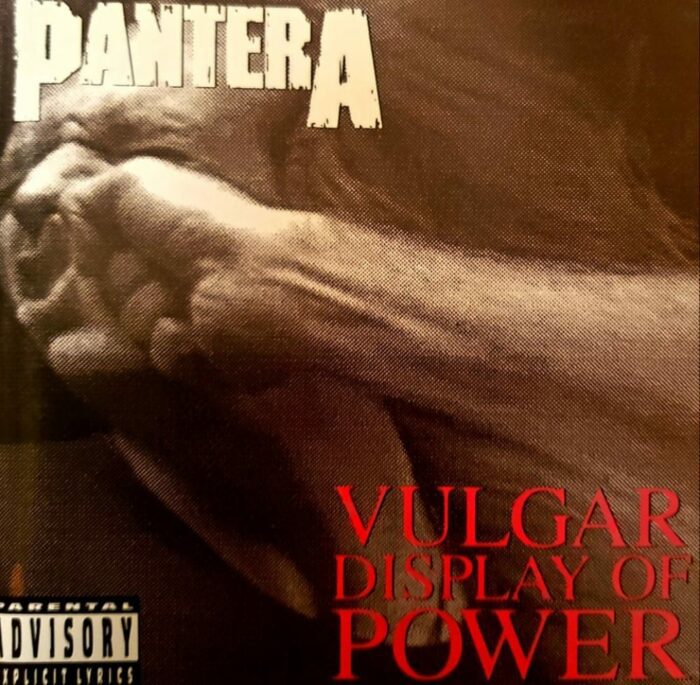

My neighbor first exposed me to Pantera. He thought I’d enjoy the band, so passed me a cassette entitled Vulgar Display of Power. He essentially tossed a flare into a pool of gasoline.

In a way, I lucked out. It was roughly 1998. By then Pantera had already released four albums. Technically, they put out eight going all the way back to 1983. However, many fans mark Cowboys from Hell as the real beginning. That’s when the band nailed the groove-oriented sound they’d become synonymous with. The point being, I didn’t have to wait for new records. I found a deep rabbit hole to dive down. And at the bottom, in a razor wire wonderland, I discovered The Great Southern Trendkill.

The difference between every Pantera album is an obvious escalation. Each intensifies bringing new degrees of brutality yet does so with a smooth groove keeping everything musical. This isn’t just ham-fisted drums and speed chugs. There’s a musicality missed by those who turn up their nose.

Guitarist Dimebag Darrell often utilized simple riffs to create concrete crushing grooves but could shift into complex shreds and solos with effortless ease. Vocalist Phil Anselmo quickly evolved from a piercing falsetto howler into a gravely snarler yet kept both tools on him. Meanwhile Vinnie Paul provided more than mere beats, his drums stand out as distinctive as any guitar lick. Finally, bassist Rex Brown brought a dancing jackhammer into the mix.

“You keep this love!”

I’ll never forget the first time I heard The Great Southern Trendkill. I was sitting in a car with a young lady. She wanted to show me some of her favorite songs. So, we slipped away from friends to be alone in a dark garage. After a bit of Slayer, she opened a jewel case adorned with a rattlesnake and slid a disc into the slot. Looking back, there’s a romcom quality to the whole scenario. Two teens attracted to one another; avoiding awkward conversation by letting the music speak for them. That is to say, Phil Anselmo bellowing like an angry bear while the rest of Pantera sonically broke our bones. Every love affair should start so intimately.

Besides my neighbor, she was the first person I met who enjoyed Pantera. Many of the metalheads I knew preferred Anthrax, Metallica, or the burgeoning nu metal scene. Granted, I liked those bands too, but I never really got a chance to listen to what I loved with another fan. It allowed the opportunity to get a little introspective.

There’s often a causality dilemma when it comes to music and personality. Like the chicken or the egg, did my personality attract me to heavy metal or did the music make me the way I am? I’m reminded how Deftones guitarist Stephen Carpenter once referred to Meshuggah as the “quantum physics of music.” It calls to mind thought experiments such as Schrödinger’s Cat and Wigner’s Friend. Essentially, the thinking is that a state of being doesn’t exist until observed and music is a way of observing one’s self.

“Now you’re living through me.”

The unrelenting beginning to The Great Southern Trendkill is both invitation and warning. The titular track and second song “War Nerve” constitute a polemic, borderline screed, against the perceived enemies of Pantera. Specifically, the way the music industry and critics seemed disinterested in metal.

Record companies at the time, motivated by grunge’s commercial success, often pushed for a softer sound. According to Sodom frontman Tom Angelripper, “Many bands changed their music… they got pressure from labels to sell more and get a commercial direction.” Consequently, thrash metal monsters like Testament put out more melodic, accessible albums like their 1992 record The Ritual. Granted, they switched to a harder sound on their follow up Low. However, according to lead singer Chuck Billy, the “angry record” ended up getting them bounced out of Atlantic Records. As Metallica appeared to abandon thrash with albums like Load and Reload, it reminded many in the metal community of their outsider status.

To someone who responds to such music, the perception of metal as unwanted feels like society reaffirming it has no interest in you. This fueled the seemingly contradictory nature of a band like Pantera’s success. They claimed to be part of a maligned movement even as they sold millions of records. Their album Far Beyond Driven hit number one on arrival. It seems like saying they were losing while sweeping in arm loads of gold. Yet, the reason they could reap such rewards is because their music spoke to most of the metal tribe.

Still, the lyrics on The Greath Southern Trendkill aren’t just acid spewed at critics and a greedy industry. At one point in “War Nerve,” Anselmo growls, “F*ck myself, don’t leave me out.” Though the line is delivered with snarling swagger, it’s a revealing instance of self-loathing. It signals the all-consuming nihilistic anger that encompasses the album. Since, at the end of the day, you can’t hate everything without hating yourself.

In addition, it opens the door on interpretation. Pantera may’ve been railing against the media, but the sentiment is resistance to judgmental individuals. Lyrics like “It’s forcing you down/And it’s grinding against you” resonate with anyone who never fit in.

That said, when Anselmo growls to “let the war nerve break” it’s simultaneously a call to arms and a grim acceptance pressure inevitably causes a snap. It’s a song for the broken bottles who can’t hold things in anymore. All they can do is cut.

“Drag the waters some more.”

As musician Moby observed, the lyrics to The Great Southern Trendkill are a “vituperative expression of anger and rage.” Bitter and abusive lines lurk throughout the record and paraphrasing one track’s title sums it up best. A listener is sandblasted, stripped of any façade, and left with no choice except raw emotional reaction. While anger is obvious, sadness abounds in songs like “10s”, “Suicide Note pt. 1”, and “Floods.” Regret pervades the tracks “Living Through Me (Hell’s Wrath)” and “13 Steps to Nowhere.” Yet, a melancholy joy exists thanks to oscillations in tone.

Consider the two-punch combo of “Suicide Note pt. 1 and 2”. The first is an acoustic, I dare say anti-ballad, yearning for death. A somber reflection on a life aimed at the grave. The second part, however, violently rejects notions of suicide and curb stomps any romanticization. Where before Anselmo crooned, he now screams, “Cowards only try it/Don’t you try to die.”

Similar shifts exist within the instruments as well. The titular track is a machine gun blast that eventually cools into a bluesy groove. Drums in “13 Steps to Nowhere” provide a marching beat then skull thumping double kick. A walking bassline leads a listener steady on through the harshness of “Living Through Me (Hell’s Wrath).” That same bass assists the guitar on “Floods” which contains a soaring metal solo, easily one of Dimebag’s best; the kind of music one expects to hear when epiphanies hit, and life gains a semblance of sense. But right afterward is the blistering onslaught of “The Underground in America.”

Overall, masterful instrumentation complements lyrical content. Each enhances the other making the whole more meaningful. The Great Southern Trendkill then serves as a validation of all the dark notions swirling in someone’s head. Though critics like Steve Appleford might regard the record as a monotonous soundtrack to a little boy’s tantrum, the gritty realism appealed to metalheads like myself. Not simply because we could discern the instrumental complexity critics smugly ignored, but because it literally sang to the soul.

The record and its sales basically said you are not alone. That these feelings of anger, isolation, depression, and self-loathing are, unfortunately, normal. Screaming along with Anselmo and headbanging to Rex, Vinnie, and Dime offered a kind of catharsis. As I sat in that garage listening with another member of the lost and the damned, it couldn’t’ve been clearer: the world is a terrible place, but its horrors, if not conquerable, can be endured.

“Cemetary Gates”

In December 2004, my Dad called me up. He asked if I had seen the news. No idea what he meant, I asked why, and he informed me that Darrell “Dimebag” Abbott had been murdered on stage. A deranged fan shot him during a show in Columbus, Ohio. One of metal’s most significant guitarists was gone forever.

My Dad asked, “How many guys are in that Panera [sic] band?”

I told him four.

He laughed, “One down, three to go.”

That night I went to a bar near my apartment in Chicago. I sat for a long while listening to Pantera CDs and drinking whiskey by myself. It’s an odd thing feeling a sense of loss over what’s essentially a stranger. Knowing the man’s music didn’t make us friends. Still, I couldn’t escape the absence.

Furthermore, it closed the book on Pantera. By then the band had dissolved but the possibility of future music, at the least the hope for more, lived in every fan. After all, musicians have been known to reunite. With Dimebag dead, there’d be no reunion.

Any optimism glimmering otherwise vanished when Vinnie Paul passed away on June 22, 2018. By then I was living with my Dad, taking care of him due to his declining health. Perhaps because of that, decrepitude and death creeping up on the old man, he responded very differently to the drummer’s demise. My reaction, however, remained much the same.

The past is rarely alive. The closest it feels to still being around stems from those things intertwined with memories. Familiar music is one of the most expedient means of stirring nostalgia, and when its creators die, it triggers a whole reflection on all the instances that music connects to. It’s hard for memories not to get a little bittersweet when someone contributing to the soundtrack will never add another song. In a way, the past dies with them. At the very least, it feels a little less alive.

Even the fury of The Great Southern Trendkill can’t resurrect the dead. At best, it can only summon ghosts. And sadly, although those specters visit until the record stops, they have nothing new to say.

“I Can’t Hide.”

It’s tempting to ignore the elephant in the room. Essentially, accusations of racism have orbited Pantera for years. Phil Anselmo’s actions over the years haven’t help dissuade such notions. For instance, the time he threw up a white power salute. Although he apologized for the incident, it isn’t the only thing leaving a bad taste.

The Confederate Flag adorned a lot of Pantera merchandise. During live shows, it flashed over the stage in laser light displays. When a hard push started for a nationwide end to the flag’s use, Vinnie Paul seemed to lament what he called a “knee-jerk reaction to something that happened.” Given when he made the statement, that something provoking the knee-jerk was probably white-supremacist Dylan Roof murdering nine African Americans.

Oddly enough, Anselmo commented on the flag saying, “These days, I wouldn’t want anything to f*cking do with it.” He also expressed regret for having used it in the past. Still, there’s an argument to be made that The Great Southern Trendkill carries an “implied subtext” about “moving too far towards a restrictive PC culture.” As Saby Reyes-Kulkarni wrote, “One has to wonder what else was on [Anselmo’s] mind that he didn’t have the guts to say flat-out.”

According to Dimebag Darell, the song “Drag the Waters” is about “a lifetime of dealing with people that you can’t tell… what their motives really are. You’ve got to drag the waters to get to the bottom and find out the truth.”

I think many fans are sensitive to this issue because of a potential guilt by association. If Pantera is racist, even in part, there’s an implication that their fans, at the very least, are okay with that. Consequently, fans aren’t just defending the band but themselves when they argue against such accusations. However, instead of embracing fallacious arguments like heritage, not hate, perhaps a better stance might be admitting what seemed acceptable was always a mistake. That even if Phil is simply a fried edgelord with tasteless jokes, no one is laughing.

If metal is the music of rebellion, it can’t be afforded blind acceptance. Any deference risks compromising important principles. Furthermore, it’s not so much about censorship as offering the opportunity for someone to be better. And acknowledging imperfections isn’t a weakness. It’s the very fearlessness heavy metal is supposed to inspire.

“Goddamn Electric”

On Pantera’s final album Reinventing the Steel there’s the line, “a part of me that’s always sixteen.” Sung on “Goddamn Electric,” it’s a celebration of heavy metal. From wild tunes to unapologetic hedonism, the track glories in the eternal youth that music provides. Despite the screams and rusty snarls, it’s actually a very happy song. Just press play and in a way, the past is alive again.

By contrast, The Great Southern Trendkill is the soundtrack to a psycho holiday. Though the art of shredding is never more masterful, the album is a heavy metal nail bomb. At a glance, it seems to reconnect a listener with psychosis and despair. However, revisiting the past shouldn’t be all sunshine.

When I listen to this album, I get a chance to remember who I was and reflect on the ways I’m not sixteen anymore. The problem with nostalgia is a tendency to wallow in bygone glory days. Comforting as those memories may be, those moments don’t exist anymore. Sure, there were quality times, headbanging around a keg while blasting tunes, but there were darker instances as well. Ignoring them makes for an incomplete picture and that portrait is of a fractured young man, crippled by mental illness, raised to be submissively silent. I like to remember that person because I’m not him anymore.

Albums like The Great Southern Trendkill offered an outlet, a means of self-expression I lacked in my youth. Rather than explain things, just play a certain song. Even its darkest elements remind me of where I’ve been as well as what I’ve grown beyond. At sixteen, its aggressive insanity felt like an emergency exit in a burning building. Nearing forty, it takes the shape of a warning sign.

Now, that said, not every playthrough is a visit to memory lane. Sometimes a song is just a song. It puts electric in a listener’s veins and a swagger in their step. But it’s good to know hearing The Great Southern Trendkill is a way to remember where you come from.

This is a really beautiful review. Sums up so much of how I feel about this album and so much else.