The following contains spoilers for Scenes from a Marriage Episode 4, “The Illiterates,” including discussion of its explicit sex and violence.

When last we saw Jonathan (Oscar Isaac) and Mira (Jessica Chastain) at the end of Episode 3 of Hagai Levi’s updated Scenes from a Marriage, the couple’s relationship had fallen further apart, this time after a rather hapless attempt of Mira’s to reconnect following the fractures in her relationship with Tel Aviv tech exec Poli. In Episode 4, like Bergman’s titled “The Illiterates,” the two meet at their house once more, this time to sign divorce papers, but not before a volley of sexual and violent fireworks explodes onscreen. And for them it looks like the end of the relationship, if not the series.

Watching the pyrotechnics of Episode 4 ignite as they do seems like an occasion to recall just how incendiary Bergman’s original was in his time. In 1973, when his series appeared on Swedish television, only a few channels existed. No cable television existed to provide competing programming. No video-recording machines could archive over-the-air content. And no internet sites offered spoilers or recaps. In short, Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage was appointment television: the only way to keep up with the week-to-week travails of conflicted spouses Johan (Erland Josephson) and Marianne (Liv Ullmann) was to be on that living-room sofa at the exact moment the program commenced.

And so, in 1973, an estimated half of Sweden’s population did just that. Perhaps even more remarkable is that they witnessed, on national broadcast television, a sex scene that was starkly, if not visually, explicit. When Marianne arrives at Johan’s office building to sign the divorce papers, she invites and soon initiates sex on the carpet with him. There’s no fade-out. In fact, the sequence lasts a few minutes and focuses its longest take exclusively on Marianne’s pleasure, as Bergman closes in on Liv Ullmann’s expressive, radiant face. Marianne lets her hair down and directs Johan where and how to do what will give her satisfaction. I’m reminded that decades later, the MPAA initially stuck Boys Don’t Cry with an NC-17 rating for a close-up of a woman’s pleasured expressions it felt was just a little too long.

In Levi’s contemporary update—except for the major gender-swap he engineered in Episode 2—the narrative follows Bergman’s closely. So here it is Mira who arrives at their home to sign divorce papers and it is Jonathan who initiates sex. Their house is in the throes of moving, with packing boxes everywhere. Jonathan is on his way to Berlin and Vienna for academic conferences where his scholarship has finally gained traction. His and Mira’s sex is less missionary and more explicit than Johan and Marianne’s—no surprise there, given the relaxed restrictions of contemporary subscription channels and streaming services—but quickly afterward he balks at any intimacy with Mira. Minutes later, he is scrubbing his privates in the shower. He appears on some level repulsed by her, by sex, or by both.

Of course, Bergman’s spouses expressed, verbally and pointedly, their own disgust. Not too long after their mutually satisfactory sex, Johan and Marianne were back at insults, him telling her she is “worse than any whore” and she calling him “a useless parasite.” In a rare moment of relationship insight, Johan reflects that the two of them are “emotional illiterates,” the phrase that conceives the episode’s title. Johan concludes, “we haven’t learned a thing about our souls.” The phrase rings equally true for Levi’s characters: Jonathan and Mira are educated, accomplished, and articulate, but when it comes to emotional intelligence, both are lacking, nearly illiterate and prone more to insult than empathy.

Mira’s career, just like Johan’s in Bergman, is now on a marked downswing. She hasn’t been making her share of payments for daughter Ava’s pricey dance lessons, and soon she divulges why: she’s been fired, or technically “invited to resign.” Since the first episode of the series established Mira as the primary breadwinner, I’ve wondered how Levi’s gender politics were going to play out. Bergman’s Marianne found herself on a slow, stilted, but nonetheless demonstrable journey of emancipation. Are we to expect something similar for Levi’s Jonathan? Will the humbling comeuppance Bergman’s Johan received apply to Mira as well? And if so, what might either mean for an era so different from Bergman’s?

Here is where Levi has had to do the most work to update Bergman. Some updates are incidental, really: a voicemail instead of a handwritten letter, smartphone pics instead of prints. In reversing the gender roles so that the wife is now the breadwinner and adulterer, Levi has solved one riddle of the original’s dated gender politics only to encounter another. Do contemporary men need a tale featuring some sort of journey of emancipation from their newfound domestic straitjackets? Rather than lean into the pop psychology of a turn-of-the-century Susan Faludi, Levi looks inward to his own personal experience: “Everything that has to do with [Jonathan’s] character, I took from my reality, including the religious background, including all the inhibitions.”

To be fair, so did Bergman himself. Diverse as his work may be, much of it remains grounded in his personal experience. And a whole subset of scholarship is devoted to the ways his biography is reflected in his films. So in a sense, Levi is making Jonathan’s character his own in the same ways Bergman had, as the original series itself was motivated by Bergman’s relationship with Ullmann. Jonathan’s inabilities to connect intimately with his wife make the most sense if seen as something of a rationalization for Mira’s reactive behavior in Episodes 2 and 3.

Through the fourth episode of the series, however, neither character seems fully realized. The revelation of the affair stuns viewers as much as it did Jonathan, and for the most part, Isaac’s character has become in the gender swap a void, a stay-at-home father and academic we almost never see parent or teach. He has neither the career frustrations of Bergman’s Johan nor the unequal marital status of Marianne; as a consequence, the character feels more than a little milquetoast, an earnest parent cuckolded by the narcissistic career woman and hamstrung by his own apparent intimacy issues.

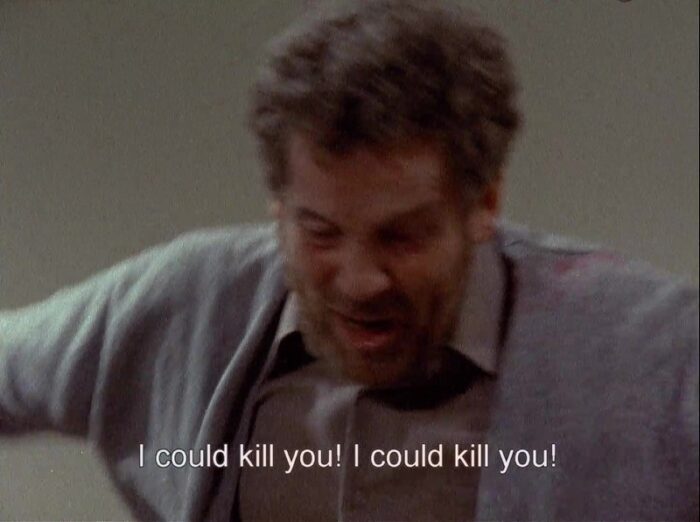

Viewers familiar with Bergman might know well where this penultimate episode will conclude. After Johan and Marianne continue with more drinking, more arguing, and more almost-but-not-quite signing of the divorce papers, their night turns violent. The revelation that both have new mates seems to trigger each of them. Finally, Marianne loses patience, becomes disgusted, and calls a cab. Johan pushes and threatens her; she taunts him in return, before he strikes her, again and again, drawing blood. Enraged, he becomes even more violent, kicking Marianne a half-dozen times and ranting “I could kill you!” before collapsing in resignation. The episode is as frightening a depiction of domestic abuse as one can imagine and it’s still remarkable to contemplate its appearing on broadcast television in the 1970s.

Only then, as Marianne pulls herself together to leave, does Johan finally sign the papers, as does she. Marianne, a divorce lawyer, ruefully notes her own advice to clients: “I constantly warn women in the process of divorce not to find themselves alone with their aggrieved husbands.” Bergman was not especially shy about depicting violence onscreen—his 1960 The Virgin Spring was notorious for its explicit depiction of rape—and here Johan’s violence is palpable even if the blows themselves are depicted offscreen. In each of my episode reviews I’ve complimented Chastain and Isaac, but I should reiterate also that Bergman’s actors were incredibly persuasive in their delivery as well. In this episode Josephson veers from impish to vile, charming to threatening, submissive to abusive, utterly convincing at every turn.

We’d seen back in Levi’s Episode 2 a brief foreshadowing of the couple’s physicality when Jonathan forcefully pushed Mira away from the suitcase he was packing for her. True to the series’ gender-reversal, here in Episode 4 it is Mira, frustrated by Jonathan’s leaving, who initiates the violence, blocking his exit and throwing the first punches. I know that men can suffer physically at the hands of violent women and size alone does not determine the consequence of an attack, but here the petite Chastain does not really seem a serious physical threat to Isaac’s character. The incident pales in comparison to the unbridled rage seen in Bergman, but is nonetheless a distressing, disappointing, disturbing turn in Jonathan and Mira’s marriage, one that has come to seem more unsalvageable at the end of each successive episode.

After the incident, the two calm down and sign the papers; Jonathan then leaves, wordlessly, looking back at their house in the night. With the papers signed and their relationship having devolved into an evening where sex lacks intimacy and argument ends in violence, there seems like there’s little left to the relationship other than a duty to co-parent. For the first time in four episodes, Jonathan finds himself outside the house, not unlike an Ibsen heroine Bergman’s characters would discuss. He looks back at the house as he slowly drives away in the night, ready, finally, for a life that does not revolve around his wife’s career.

In Bergman, the eruption of violence in “The Illiterates” was timely and consequential. It came at a moment when the third wave of activist feminism began to fight back against domestic violence. For too long had too many men been able to use their physical advantage to oppress women; hotlines, resource centers, and education programs in the 1970s evolved as a way of countering domestic violence. Johan’s beating of Marianne is one that in real life not every woman would survive. Difficult as it was—and even is still—to witness, the scene was one that was motivated, plausible, and frightening. In the context of the times, Johan’s eruption made perfect sense to include, even if it was bound to surprise and horrify its television audience.

The domestic violence that erupts between Levi’s protagonists, in comparison, seems plausible but without significant consequence beyond their own relationship. The National Domestic Violence Hotline reports that 24 people each minute and 12 million per year are victims of rape, physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner in the U.S. Of victims of intimate partner violence from 1994 to 2010, approximately four in five were female. (I might add that transgender individuals are found to be 2.5 times as likely as cisgender to experience sexual intimate partner violence.) Levi’s gender swap notwithstanding, however, a man like Jonathan is simply far less likely to be a victim of domestic abuse than a woman like Mira.

Episode 4 of Scenes from a Marriage shows us Jonathan and Mira at their nadir. As Jonathan finally, for the first time in four full hours, leaves their house, it’s time to exhale. The two have lived through an abortion, adultery, argument, a lack of intimacy, and now a lapse into violence. Their Scenes from a Marriage are ones that show more the process of breakup than the functioning of a relationship: in “The Illiterates” we’ve now seen Jonathan and Mira come to blows—and then, ultimately and resignedly, to terms.

Where can they go from here?

Bergman’s final episode was titled “In the Middle of the Night in a Dark House Somewhere in the World.” Next week’s final episode is one you can expect will land there, somehow, as well.

24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, the National Domestic Violence Hotline provides tools and support to help survivors of domestic violence. Call 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE) or visit www.ndvh.org.