Promotional material for The Many Saints of Newark promises answers to some long-burning Sopranos questions—but take that with a grain of salt. It’s impossible to know to what extent a movie’s creative team is involved in its marketing. Did David Chase, creator of The Sopranos and co-writer of its prequel, come up with the tagline “who made Tony Soprano?” The world may never know. Marketing teams can write checks the director never meant to cash, as Guillermo del Toro won’t hesitate to tell you.

When it comes to the matter of “who made Tony Soprano?”, though, The Many Saints of Newark isn’t playing coy. Dickie Moltisanti is right there on the poster. But the logistics of how Dickie “made” Tony aren’t as straightforward (spoilers for The Many Saints of Newark from here on out!). The film reveals that Dickie, on the advice of imprisoned uncle, was going out of his way to keep Tony away from the Mafia. Dickie accomplished this by avoiding his nephew altogether, sending Tony into a lonely rage. After tossing speakers that Dickie stole for him out of his bedroom window, Tony declares that he wants nothing to do with the family business.

After Corrado Soprano has Dickie killed, the film closes with a surrealist, symbolic gesture: Dickie’s dead body reaching out to interlock its pinkie with Tony’s as he stands over Dickie’s coffin. The implication is that Dickie’s death was the last straw for Tony—the watershed moment that set him on a criminal path. But given how limited his role is in the film, some may not find that explanation sufficiently compelling. How, exactly, did Dickie’s murder turn Tony’s reluctance to join the Mafia into acceptance? The Many Saints of Newark is a very crowded movie, and not all its revelations are convincingly fleshed out. Lucky for Sopranos fans, however, the show sheds light on some of its prequel’s blind spots.

Ever the layered, metaphorically rich text on organized crime in decline, The Sopranos is as culturally relevant as it was two decades ago. The parallels the show draws between Tony and his son—the original “little Tony”, one could say—reflect backward in time to deepen the relationship between Dickie and Tony. In light of the father-son relationship of its source material, The Many Saints of Newark becomes a far more interesting movie.

A.J. Soprano as Young Tony

A junior in more than name, A.J. Soprano is as clear a vision of young Tony as one could get. The Sopranos paints A.J. as Tony Soprano in miniature through years of evocative parallelism. The thematic bridge between father and son is constructed from the show’s first episode. It intensifies when A.J. suffers his first panic attacks—the affliction that served as the impetus for The Sopranos’ “mobster in therapy” narrative. In the episode “Army of One”, Tony bemoans his son’s panic attacks to Dr. Melfi, seething that A.J. inherited “that putrid, rotten, f*ckin’ Soprano gene”. Melfi responds with a classic bit of psychoanalysis: “when you blame your genes, you’re really blaming yourself.” Blaming himself indeed.

From the first season to the last, A.J. devolves into Tony’s spitting image. Their personalities differ, of course: Tony’s rage results in malicious, violent outbursts, while A.J. maintains a sheepishness that sours his taste for violence. Deep down, though, their souls share a tortured kinship. It’s written in their DNA, on their faces, and in their history.

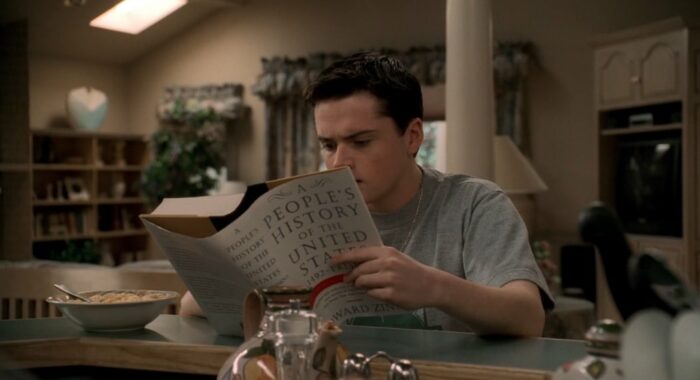

The Many Saints of Newark offers a peek at that history. The latter half of the film takes place when Tony is in high school, echoing the place that A.J. was in for much of the show. Their high school experiences are markedly similar: they both steal exam answers, neglect their academic endeavors, and surround themselves with an incipient crew. Later in the show, Tony rags on his son for dropping out of college, but Tony gave up on higher education too.The Sopranos draws a distinct parallel between Tony and A.J.’s reasons for dropping out: they were disillusioned and depressed, and had an easy way out if they ever so chose—what else would they be good at, anyway?

In the episode “College”, when Meadow asks Tony why he abandoned school for the mob, he responds dejectedly, “maybe I was too lazy to think for myself. Considered myself a rebel…maybe being a rebel in my family would have selling patio furniture on Route 22.” Meadow wonders, “In college, nothing interested you?” Tony replies with a sentiment that could easily be attributed to A.J. in later seasons: “I barely got in.”

Discussing his son’s trajectory with Dr. Melfi two episodes later, Tony reiterates the same hypothetical alternative: “sometimes I think about what life would’ve been like if my father hadn’t gotten mixed up in the things he got mixed up in—how life would’ve been different. Maybe I’d be selling patio furniture in San Diego or whatever.” A familiar disdain creeps into his tone at the thought of working an unglamorous nine-to-five. A.J. echoes that same attitude when faced with dead-end jobs in later seasons.

Whether forced into construction, skating by at Blockbuster, or managing a pizza place, A.J. expresses a tremendous lack of interest in routine, quotidian work. In the series finale, the direction of his career path is incredibly telling. Scraping rock bottom and at the brink of joining the army, A.J. receives a job on a silver platter: working for a production company run by Carmine Lupertazzi Jr., a longtime Mafia associate. Like Tony did after the death of his mentor in Many Saints, A.J. opts for an easy, nepotistic, and potentially criminal path. During the last scene in which A.J. appears alone, he gleefully squares his purchase of a gas-guzzling BMW with his on-and-off-again environmentalism—at least it’s not an SUV! A.J.’s arc is complete: internally fraught, undeservedly successful, and able to rationalize away his hypocrisy, he’s the mirror image of a young Tony Soprano.

If Tony is indeed whacked in the show’s last moments, as many have surmised, A.J. would be sitting face-to-face with his murdered father—just as Tony stood face-to-face with a murdered father figure at the end of Many Saints. The ways in which these events reflect each other deepen the film’s surface-level approach. Having enjoyed the luxury of an expanded runtime, A.J. is a fuller character at the end of The Sopranos than Tony is at the end of the prequel. One can easily imagine how A.J. would react to his father being killed before his eyes—especially given his mindset in the show’s final seasons.

In one of the show’s most thematically significant episodes— “Kennedy and Heidi”, wherein Tony murders Christopher and has a revelation while high on peyote—Tony and A.J. are juxtaposed in an evocative manner. While Tony is off sleeping with his dead nephew’s mistress, A.J. is mired in the depths of misery after abetting his friends in a racist hate crime. The Sopranos is no stranger to depicting racist violence, and that thread is picked up with greater emphasis in The Many Saints of Newark: the film stresses how the racial tension of the Newark riots shaped the city’s crime families. In a similar vein, The Sopranos explores how the backdrop of the Iraq War shapes A.J.’s conception of his surroundings. His worldview is plagued by senseless violence and lies.

Amid the climactic scenes of “Kennedy of Heidi”, A.J.—who’s been following the War on Terror with pointed interest—fails to hide his despondency from his therapist. “You sound depressed again,” his therapist oh-so-astutely observes. “I mean, how could anybody not be?” A.J. lashes back. “You’d have to be f*cking nuts not to be. I mean, you’d have to have your head wedged so far up your ass that all you could see is your own stupid face! […] I mean, everything is so f*cked up. Why can’t we all just get along?” A.J. bursts into tears.

Cut to Tony, high on peyote and having the time of his life, winning roulette over and over and celebrating Christopher’s death—his head so far up his ass that he can only view the tragedy in the context of how it benefits him. Tony’s detachment from his son’s suffering is, in some ways, worse than Dickie’s detachment from Tony: Dickie was trying to do right by his nephew; but Tony’s off in his own world, entertaining his selfish impulses. His deficient involvement in A.J.’s life is encapsulated by a moment in the following episode, when Tony and Carmela join A.J.’s therapy session after his suicide attempt. In the middle of an important conversation concerning his son’s mental health, Tony zones out and picks the tooth of a man he’d just curb stomped out of his pant leg. No wonder A.J. isn’t doing well.

After A.J. mourns to his therapist in “Kennedy and Heidi”, the episode cuts to a quieter scene: a sanitation worker, burdened with a dangerous amount of asbestos due to one of Tony’s scams, dumping the hazardous material in a local lake. Ducks are heard quacking over the sound of the machinery. Ducks, of course, are a symbolic mainstay of The Sopranos, invariably representing the kernel of innocence left in Tony’s soul. But like he poisons the ducks in the lake (albeit indirectly), Tony sacrifices what’s left of his moral center in exchange for the trappings of wealth: a nice car, a big house, an easier life. The American dream.

A.J. says it himself in the series finale, launching into a political rant during dinner (prior to his lucky employment, of course): “You people are f*cked. You’re living in a dream […] The world…don’t you see it? I mean, Bush let Al-Qaeda escape, in the mountains. Then he has us invade some other country? […] It’s like…America. This is still where people come to make it. It’s a beautiful idea. And then what do they get? Bling? Come-ons for sh*t they don’t need and can’t afford?” That’s certainly what Tony, with all his exorbitantly expensive habits, is in it for to some degree. He did, after all, grow up in an era of Newark’s history that was defined by material lack. He’d do anything to avoid the comparatively modest lifestyle he lived in The Many Saints of Newark.

Echoing his father to the end, A.J. eschews a modest lifestyle by embracing his corrupt career path and shiny new car. What better distraction from the wars and injustices raging around him? For Tony and then for A.J., the American dream is the ultimate enabler. When it comes to The Many Saints of Newark’s popularized question— “who made Tony Soprano?”—one need look no further than the title of The Sopranos’ finale: “Made in America”. Mapping A.J.’s characteristics onto a young Tony in this context makes the prequel’s ending a whole different beast.

Were A.J. to see his father murdered in front of him at the show’s end, his depression, disillusionment with the world, and lack of self-confidence would come to a head. His propensity for anger would evolve into a tendency. He’d feel like the walls were closing in around him, like his only way out would be the path just offered to him: a connection to the family business. When maintaining the parallels between Tony and A.J. across the TV-film divide, A.J.’s downfall closely resembles Tony’s in Many Saints.

Tony’s academic performance is poor, setting him up for a losing game against America’s ruthless capitalism. He was defined by an era of violence, raised by riots that laid bare the oppressive nature of his country. He just lost a father figure, suddenly and without clear reason. Imagine the broken, lost, and cynical A.J. Soprano in the immediate aftermath of his father’s death and mirror those characteristics onto young Tony, standing over Dickie’s dead body. It’s a powerful enough portrait to obliterate Tony’s claim that he wanted nothing to do with Dickie’s livelihood. The climax of The Many Saints of Newark may fall flat, but in view of The Sopranos—particularly of A.J. Soprano—it hits harder than it ever could on its own.

Excellent analysis and outstanding first entry, looking forward to more (please).