I have always been obsessive about history. I love the feeling I get when I learn about how people lived in the past—the stories, the lives and loves, the political intrigues. Despite this love, I was never interested in the American Civil War. Wars in general were not really my thing. Every now and then I like to explore the causes and the ways they affected people, but even doing that much about the Civil War didn’t interest me. Where I grew up, to be really into the Civil War usually meant that one was really into a whole bunch of other things, too—things represented by the battle flag of the losing side—and I have never had any interest in being a part of any of those associations. The documentary series The Civil War: A Film By Ken Burns is different though. I have always loved it, and not just for its importance historically; I love it on its own merit.

The Cause: Setting the Stage

The Civil War wasn’t the first Burns docuseries I ever saw, and I would argue it isn’t even the best one. (The answer to both my first and the best is Ken Burns’s Baseball.) But there would be no other Burns documentaries without The Civil War, and it was the series that changed both documentary filmmaking and commentary on the Civil War forever. Some of these changes have increased the visibility of historical filmmaking and documentaries, while other changes quite possibly have harmed us all. The first and most striking aspect of the series is its scope.

This was not an overview documentary that was going to condense the subject down into something easy to follow. What Burns and the rest of the creative team set out to do with The Civil War was possibly unprecedented. It was an entire television series devoted to one subject, and every bit of its gory underbelly and seemingly infinite amount of controversy is covered in some way. Of course somehow, despite being nine episodes long and logging in at nearly 11 hours, the series is very light on discussion of slavery, the original sin of the United States, but we will get to that in a bit. First, let’s focus on the creators themselves and what drew them to create this series.

A Very Bloody Affair: The Creation of the Series

The Civil War took more than five years to conceive, plan, and produce. Over the course of that time, thousands of interviews were conducted, some with historians, some with contemporary writers and performers, and some with people with some association with the war. The creative team scoured photographs, lithographs, paintings, and newsreels to find inspiration for stories. The writers, Geoffrey C. Ward and Ric Burns, then took all of that material and wrote a series of nine episodes. Much like in a traditional fictional series, the script for each episode follows a particular arc of some aspect of the war,

All nine episodes are structured to fit together to tell the story of the war from the causes to the aftermath in a compelling way, focusing on key characters, plot points, and events in a narrative manner. To make this work, editor Paul Barnes had to cut together the story from hundreds of hours of footage. There have been numerous stories of the difficult decisions about which things made the cut of the final film as Barnes’s work wound up leaving entire storylines, important historical figures, and major battles and developments on the cutting room floor. What is left, though, is a remarkably concise 11 hours that tells a deeply moving tale in a unique way.

Of course, the person most associated with making the series unique, and with making The Civil War an essential piece of storytelling, is the series creator and director, Ken Burns. Burns was already an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker prior to creating this series, but it will almost certainly be the leading line on his obituary one day. As creator and director of the series, it is certainly Burns’s central vision that shaped and inspired the project.

According to various documentaries, Ken Burns was inspired to make The Civil War after viewing Mathew Brady’s extensive photographs of the war. The idea was to keep the series closely linked visually and auditorily with the actual time period through photographs and letters. In keeping with that inspiration, the series features almost 16,000 photographs, paintings, and readings from letters and journals over the course of its running time.

This focus is one of the truly outstanding innovations that Burns creates. Many other television documentaries about the Civil War had already been made, and many more than that have been made in the 30 years since The Civil War first aired in September of 1990, but very few of them are as interested in exploring the subject through the primary sources rather than using historians as talking heads or other books as inspiration. The focus of the Ken Burns series is on these letters, journals, and quotes from the soldiers and politicians involved in the struggle, which means that a large majority of the voices heard are those of white men.

Forever Free: Lifting up Black Voices

There are some Black voices that are represented in the series, though, and those voices are able to tell fascinating and evocative stories that raise the tenor of the series and allow the viewer to understand some of the scope of what it was like to be a slave or free Black person during the times presented. The most prominent of these are the great writer, orator, and former slave Frederick Douglass and the poet Daisy Turner.

Daisy Turner was the daughter of a former slave, and Ken Burns was able to interview her for the series when she was 104 years old. Her insight and poetry are essential framing and used prominently in the series. Unfortunately, she died in 1988, two full years before the series would air, so she never got to see the result of all the work, nor her own part in it. Turner’s contributions are fundamental to the best aspects of the series, and the key positive aspect of Burns’s project, to allow the stories of the participants and their descendants to set the narratives for themselves.

The frequent use of quotes by Frederick Douglass is another example of this. Douglass is one of the most famous and important figures of 19th-century history and one of the first Black voices to really break through to the mainstream white audiences of his time. There have been many portrayals of Douglass in books, film, and television. Most recently, Daveed Diggs played a sensational, though quite vainglorious, version of Douglass in Showtime’s limited series The Good Lord Bird. In The Civil War, Douglass is voiced to perfection by Morgan Freeman, whose calm and sonorous voice can register both the majesty and the depth of Douglass’s quotes.

Simply Murder: The Controversy

Despite those voices being heard, though, the plight of the Black Americans during the time period is not covered in nearly as much depth as it should be. Burns is well known for his liberal politics today, and the series is decidedly framed with the North as the ultimate heroes of the story. Of course, the series didn’t ignore historians entirely, and several of them are quite adamant in the notion that slavery was the ultimate cause of the war. Yet the historians featured in the series definitely have their own lenses through which they see the war. Barbara J. Fields, Ed Bears, and Stephen B. Oates gave essential feedback and framing for much of the information provided over the run. And while each of them has their own impact, they are certainly all well within the normal and accepted historical community of views about the impact and causes of the Civil War.

But Burns is also very interested in telling the story with as many different viewpoints included as possible. The southerners are lifted up and humanized throughout the run. There are many letters from Confederate soldiers throughout the series. Confederate officers like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are presented in a fairly reverential way. For the series, this is important because it both fleshes out the story and allows the dramatic narrative to flourish, but for history, this may have done a grave disservice.

The “Lost Cause” narrative version of history really started to gain traction around the turn of the century (the 19th century into the 20th century). The Daughters of the Confederacy were commissioning statues around the country in honor of Confederate generals. Textbooks in the South completely retold the history of the Civil War as the “War of Northern Aggression.” Throughout the 20th century, especially in the South, this became the predominant mode of thinking and talking about the Civil War. In the 1950s, in order to protest against the rising tide of Civil Rights and decisions like Brown v the Board of Education of Topeka (1954), Southern states started raising the battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia above statehouses and adding the symbol to their state flags.

In the minds of many southern white people, that flag became about the very act of rebellion itself, and the “Rebel Flag” took on its own cultural mythos—a mythos entirely subsumed in and guided by a latent notion of white supremacy and a mythical “cultural heritage.” All of this contributed to a cultural understanding of the Civil War as one in which the poor white southerners fought against tyrannical northern oppressors. These viewpoints are woven within much of the writing about the war in the 20th century, particularly in the epic three-volume history The Civil War: A Narrative by Shelby Foote.

And Shelby Foote is a key figure in The Civil War. He is interviewed, quoted, and relied upon most often by Burns and the team throughout the series. (Foote is usually considered more of a layperson historical novelist than an official historian by other historians, but I feel like the details of these precise issues are best left for a different day.) There is no doubt that Foote is a fascinating storyteller, Yet at far too many turns his viewpoint becomes the central one. And when that happens, the “Lost Cause” narrative gets a much greater spotlight than it should.

Foote becomes a star of the series, his books are given a feeling of primacy, and his voice starts to feel authoritative—all of which makes the more questionable parts of his work come into sharper focus. He explicitly states slavery was not the cause of the war—it was. He laments the lack of compromise that led to the war—a compromise that free Black people, slaves, and abolitionists absolutely could not and should not abide. His contributions (and Burns’s centralizing them) make the entire project suspect in many ways and may have led in some part to the prevailing ideas that haunt us to this day. But Foote is by no means the only person to get a spotlight in the series.

The Universe of Battle: The Voice Actors and Narration

The stellar voice work by Morgan Freeman as Frederick Douglass is just one part of an exceptional ensemble of all-stars who lent their talents to the series. The actors are each assigned a particular figure or set of figures, and they provide the voice for that “character” throughout the series. This allows the characters to feel more fully realized than they would have if they had been voiced by various people. In addition to Freeman, there are other really important standouts. Jason Robards as Ulysses S. Grant and Sam Waterson as Abraham Lincoln each provide absolutely essential moments. The storytelling is intimate and personal, as diaries from Mary Chestnut (voiced vividly by Julie Harris), Sam Watkins, Elisha Hunt Rhodes, and George Templeton Strong are featured prominently.

It is hard to imagine this series without the sound of one voice in particular, that of David McCullough, the author and historian who serves as the narrator of all nine episodes. McCullough’s books John Adams and 1776 have become classic reading on those subjects, but when listening to his voice throughout The Civil War, it feels as though it will be as the narrator of this project that he will be most remembered. The narration definitely deepens the experience, and without the dulcet tones of McCullough’s voice, it seems unlikely that the series would be nearly as memorable.

As the series progresses, the narrator starts to feel like another character in the story. He celebrates the wins. When there are losses, he expresses sadness and dismay. And when there are deaths, he seems to mourn. McCullough’s narration is omnipresent and vital, and despite the structure of the series, it never seems detached.

Valley of the Shadow of Death: The Music

Along with McCullough’s narration, the sound of the series is established through the music. A great deal of the music presented is actual contemporaneous music that the soldiers and historical figures in the 1860s would have heard and known. There are such songs as “Battle Cry of Freedom” or “Bonnie Blue Flag” that the soldiers could probably sing along with if they jumped to the present day. But the music you are probably hearing in your head right now is the one key exception. The title theme, “Ashokan Farewell,” the sad violin-based refrain that is repeated 25 times over the course of the series, was written by Jay Ungar in 1982.

According to Ungar, the song is about the “sense of loss and longing” that he felt after the Ashokan Dance & Music Camps ended their season. There is certainly that feel to the music. The solo violin sounds at the beginning playing over the pastoral images of a Civil War battlefield, now empty except for a single cannon, are certainly some of the most evocative parts of the series. The song is almost certainly overplayed, and the fact that it was not historical to the time of the war has certainly lent to confusion and frustration from people who want accuracy in everything, but it is also undeniably an essential piece of the puzzle that makes The Civil War a crowning achievement.

Most Hallowed Ground: The Ken Burns Style

The music certainly does a great job of creating a feel for the series, but it is the cinematography that really seals the deal. Burns is credited as the cinematographer along with Buddy Squires and Allen Moore. The cinematographers took some of the interests and techniques that Burns had been working with for his entire career up until this point and perfected them. I remember clearly being surprised when I first saw that there were no reenactments in the series. Those had been an essential part of all of my favorite History Channel documentaries, and the Civil War has thousands of regular reenactors to use for projects like this.

That was not the vision they were looking for, though. It is striking that all of the modern video footage is of empty battlefields, and it lends extra pathos to the scenes. By incorporating the scenic beauty of the land with the powerful music and narration, the series creates visual imagery that is so iconic that it can be described (and sometimes parodied) just by telling someone “this is like a Ken Burns documentary.”

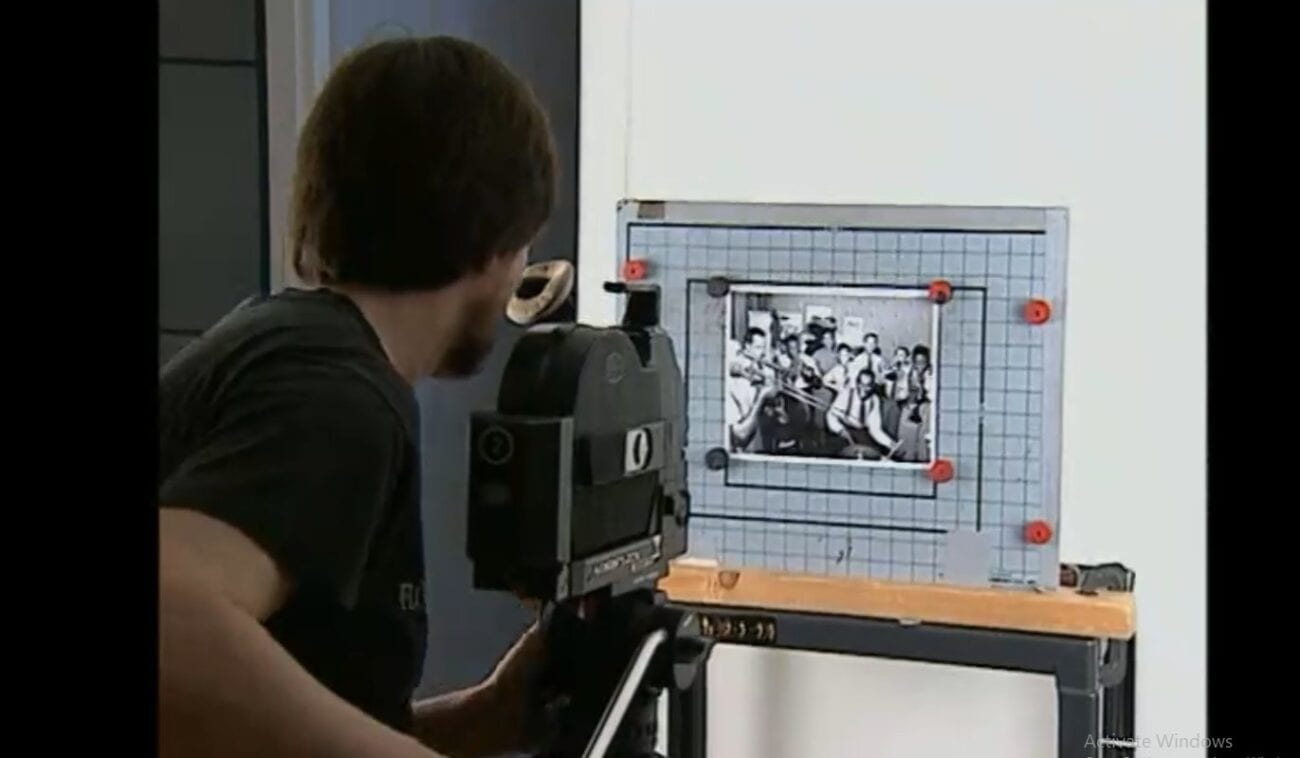

The other essential piece that has come to define the series and the stylistic choices of Ken Burns in almost every one of his projects is the technique used to film the still photos and paintings. The slow zooming and panning across images that is fundamental to this series is so associated with Burns that it has been deemed the “Ken Burns effect.” The details of the photographs leap off the screen and become etched in the memory of the viewer.

There is something unnerving and awe-inspiring about listening to the words of the people who were actually involved, usually underscored by music of the time, while looking at the faces of the actual soldiers. The indelible quality is visceral, and the moments seem real because, in so many ways, we are actually seeing and hearing them. But in the original 1990 release, there is one issue: the quality of the film itself is rather murky and low definition.

War is All Hell: Restoration and Re-release

The series was wildly popular from its first airing. It is estimated that over 40 million people watched at least one of the episodes. Since then, the homages and influence have only increased, and re-airings, home video, and DVD releases have allowed even more people to see the enormous scope of the series. What has been less successful in some of those media is the actual look of the film itself. Being made for television in the late 1980s, much of the film itself and many of the techniques used to present it have significant limitations on modern 4K HD televisions leading to the original film looking very threadbare. This is no longer the case, though, as the film has now had a gorgeous shot-for-shot restoration.

In 2015, Burns, along with film restoration expert Daniel J. White, took on the painstaking process of upgrading every visual aspect of the series for modern HD. According to Burns, this has finally allowed the project to look like he actually intended from the start. The remasters add back size on the sides because the original is cropped into the “square” aspect of the previous era’s television sets, which allows every image to have 10% more visible area. All of the shots from the battlefields have a crisper, brighter look. Basically, there are incredible improvements throughout and it is well worth buying or renting the remastered version instead of sticking with the lower quality originals.

The Better Angels of Our Nature: The Conclusion

What does all of this mean? The Civil War has had an outsized impact on the culture and on how documentary films are made. Every series or film made since has to reckon with its impact, either by leaning into the style and substance (such as the way that the many other Ken Burns documentaries have done) or by daring to be something new and different. Especially for a television docuseries, attempting to do the latter is often a struggle.

Many shows and films fall short in either category, but the ones that are most effective are the ones that emulate the right part of The Civil War. This can extend to serious subject matter in a different medium, like the podcast Serial, or it can be about an absurd and funny subject in a Netflix series like the hilarious Toys That Made Us series and its spinoffs. It is the attention to detail and unparalleled love for the subject matter that make or break the show.

In the end, The Civil War is just as vital and important now as it was 30 years ago. It does what it set out to do, which is to make the story of the war into an artistic and compelling narrative.