Editor’s Note: “Dreaming of Dana Scully” was written during the 2023 WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes. Without the labor of the writers and actors currently on strike, the series being covered here wouldn’t exist.

In the early months of 2021, I began dreaming of Special Agent Dana Scully from The X-Files. Before writing this article, I never thought to compare television or dreams (not even when Twin Peaks fans exploded in speculation about “the dreamer who dreams and lives inside the dream” in The Return). But my Scully dreams compelled me to explore the relationship and similarities between television and dreaming.

Unlike television, the dreams that come to us in sleep are largely our own creation, even if we are unaware of the creation process (unless you are lucid dreaming, of course). The assemblage of images, events, feelings, thoughts, and intuitions, whether you interpret them or not, have an undeniable connection with the individual dreamer, although in my experience, most people, if they remember their dreams at all, leave them unexplored and thus abandoned.

In contrast, the creation of a television series requires a massive group effort. Writers, directors, producers, crews, actors, editors, and composers work together to bring stories to life. Unlike a dream, a television series needs significant financial backing and relies on a certain amount of consistent collective attention to generate new seasons. But differences aside, there are many similarities between television and dreams, and I’ll attempt to use my dreams to illustrate them.

In 2021, I was working on a dissertation for a degree I did not want and ultimately walked away from. But when I had these dreams, I was still striving, as I had been for nearly a decade, to force the degree and its career path to “fit” even though I knew it was wrong for me. I made significant life choices based solely on desperation, and I chose to believe that, somehow, things would just work out, even though I felt perpetually at odds with my life. This inauthentic life, coupled with viewing The X-Files for the first time, stirred up my dream life for several months.

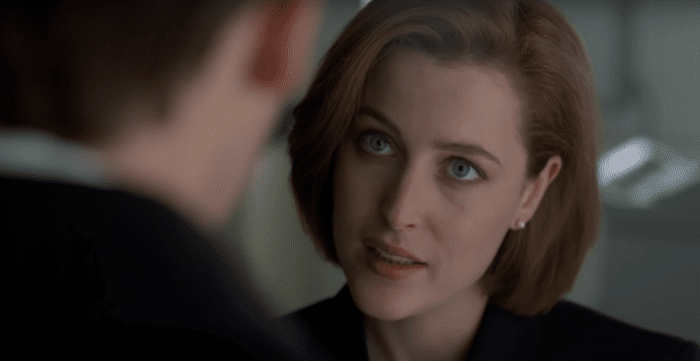

In January 2021, I dreamed of Scully for the first time. In the dream, I observe a group of men in black chasing Scully through a dense jungle. She turns and waves a pistol at them, threatening to blow up several canisters of flammable material. Then, I appear on the scene, and we escape together.

In the second dream, I am a disembodied point of awareness. I see Scully standing in a red rock desert; her arms are bound, and she is making an impassioned speech about “not giving up the fight.” Then, several neon green tendrils reach toward her face, cover her mouth, and silence her. My vision fades to black, as if the dream itself is asphyxiated.

In the third and final dream, Scully is being interrogated by a blonde female agent on a crowded passenger train. She is unmoved by the interrogator, who throws insults at her to provoke a response. Scully remains steady; she is self-assured and fearless.

Eventually, I asked myself: Why these dreams? And why Scully?

Context is important when revisiting dreams. These Scully dreams did not emerge in a temporal vacuum but manifested during a time when I was deeply out of sync with my authentic desires. Whether you say I was living in bad faith, living life as a false self, or ignoring my intuition, I just wasn’t being honest, and in the height of this dishonesty, Scully appeared.

Similarly, a television series arises in a specific temporal context. A TV show that is initially groundbreaking and explosively popular can very quickly become period piece. Like us, TV shows age (dreams do not); the very material they are filmed on becomes indicative of their era; dialogue, actors, hairstyles, wardrobe, and story arcs can quickly become dated, archaic, or even laughable. For me, The X-Files is undeniably a ‘90s TV show. It doesn’t matter that it continued into the 21st century, because in my mind, it cannot be extricated from its temporal origin. For whatever reason, I always seem to read it backwards through time. I can watch it now, but it only exists back then.

Place is another important contextual factor. In my dreams, I saw Scully in a lush jungle, an uninhabited rocky desert, and a crowded passenger train. Perhaps each locale was evocative of my life at the time of each dream (they occurred roughly 1-2 months apart), but regardless, they each formed a clear and distinct backdrop for the drama taking place in front of me. On television, this gets trickier.

The Twilight Zone, a show similar to The X-Files, with its “monster of the week” stories, sci-fi proclivities, and rampant paranoia, is obviously a television show. By that I mean the sound stages and façades are blatant and conspicuous; sometimes, abrasive lighting or poorly realized landscapes reveal the illusion, but somehow, this has an unexpected effect: it makes me enjoy the show even more. And it rarely lessens the emotional or psychological impact of the story being told, which certainly speaks to the show’s strength. But The X-Files (which, I must confess, I have only seen the first five seasons of), is, in comparison, much more immersive. The unreality of place operates in a different way.

As someone who has lived all over America (six different states), I can usually recognize whether the stated location in a TV show matches up to the actual environment (e.g., shows set in the flat Midwest but are obviously filmed in hilly southern California). The first five seasons of The X-Files were filmed in Vancouver, so when I watch scenes or entire episodes that ostensibly take place in specific parts of the U.S., I know that it is actually taking place in Canada. This adds another dream-like layer to the show. Nothing is really as it seems. It is all an illusion, yet the stories that play out on this illusory stage never cease to envelop my attention.

The episodic nature of television is also like dreaming. Some people have reoccurring dream figures; I visit reoccurring dream places—they don’t exist in any real sense, but their features remain consistent enough to be recognized time and time again. (For example, there is a place I call “The City,” which is a tumorous conglomeration of skyscrapers, retails stores, and chain restaurants surrounded by an endless beige desert. And the weather never changes; it is always raining.) Many people remember a single dream (or a single dream image) upon waking, but I often dream in serial format, such as a progression of six dreams in one night, or, in the case of the Scully dreams, a reoccurring “main” character in dreams that took place months apart. In content and in form, these dreams also resemble television episodes.

I am not interested in exploring these dreams causally, nor am I interested in using psychological theories to interpret them (e.g., “Scully is my anima,” “The men in black represent my shadow,” “The blonde interrogator is my super-ego”), but I am interested in the fact that they were both inspired by The X-Files and mimic the format of television episodes. They include drama, conflict, and a narrative progression (albeit a brief one); they feature a heroine-protagonist with a strong sense of morality and courage, as well as ominous forces, both human and alien. Clearly, I was responding to some aspect of The X-Files, but at the time I had these dreams, I think I was more or less unconscious of what this “something” was.

One of the conclusions I’ve drawn is that The X-Files, as well as any other television show, portrays not only a world but also a worldview. There are beliefs and values, both implicit and explicit, communicated in every episode with dialogue, characters, conflicts, and resolutions. The dark world of The X-Files is populated with monsters, aliens, government conspirators, and countless murderers. But it also includes characters who risk their lives in the pursuit of truth and the continuity of life. There is plenty I am leaving out, but after reflecting on these dreams, The X-Files, and television, I can see the resonance between the worldview of the show, my own experience of life in America, and the context of my life at the time I was both watching the show and dreaming of Scully.

Especially since 2020, I have been overwhelmed with conspiracies, and I am certain I am not alone in this. Government cults, microchipped vaccines, voter fraud, “staged” natural disasters, and faked shootings—all of them are, to me, ridiculous, but more importantly, they are profoundly uninteresting. Frankly, they read like poorly written fiction, and their ham-fisted intent, which is to scare people, irritates and bores me. Beneath every conspiracy lies yet another conspiracy (and another and another) which ultimately rests on a fantasy of omniscience and omnipotence that gives the knower a false sense of control over reality—that is, over life and death. But The X-Files, which I love, is riddled with conspiracies; they make up its narrative fabric, and as soon as one conspiracy is uncovered, another one (or more) surfaces, and the search for truth continues (whatever that means). As the characters spin round and round in government bureaucracy, they battle monsters, supernatural forces, and sociopathic humans. Doesn’t this sound all like a dream? Or perhaps, a psychotic episode?

In my dreams and on The X-Files, Scully is powerful, methodical, and fearless. She uses science as her lodestar but never sacrifices her heart or her instincts. There is a kind of authenticity to her character, as well as a constitutional stability, that I am certain I was responding to during such an uncertain period of my life and in the greater (paranoid) world. Perhaps her sanity and stability bubbled up in my dream life to remind me that I also contain the capacity for sanity and stability. I play the observer in these dreams because I had not yet found these traits inside myself, so I could only recognize them externally, in others. This is a normal psychological process (i.e., projection), but it is not the end of it; to live authentically we must embrace the qualities we admire and live them in waking life.

And in this case, I think I did. Six months after the last Scully dream, I withdrew from my doctoral program and let go of a career I had been working toward for a decade. Although I am still grappling with the ripple effects of that decision, and the resultant grief and frustration (what took you so long?), I can take heart that perhaps I stopped dreaming of Scully because I became more like her. Her televised presence struck something in me that manifested in my dreams and gradually helped me wake up, at which point she took her leave. This, I think, is a truth worth celebrating.

But I wonder about Scully’s partner in crime, her intuitive, mercurial, impulsive counterpart. Where was Mulder in all this? I briefly considered the idea that perhaps I functioned as a kind of Mulder stand-in, but I was only a passive observer, not a protagonist.

If I ever dream of Mulder, it will surely be because my life has become too logical, too unimaginative, and too confined. I can see him now: he is stepping toward me, illuminated from above by a harsh white light, pummeled by wind, wreathed in fog, telling me that the truth is out there—but it is not something you find, it is something you live.