“He was never looking to be compared to any other lyricist.” James Dean Bradfield

“I’d forgotten how much I missed him as a lyricist, how much a fan I am of his intellect, his fierce, rigorous critique of culture.” Nicky Wire

“Youth culture has always been controlled by the same people, selling the same goods at inflated prices – just more created products all the time. If you’re told what youth culture is, it’s not much use. Everybody knows what they want to do and then they’re told to do something else and they do it. Youth is the ultimate product. We just wanna mix politics and sex, look brilliant on stage and say brilliant things.” Richey Edwards on Snub TV, 1991

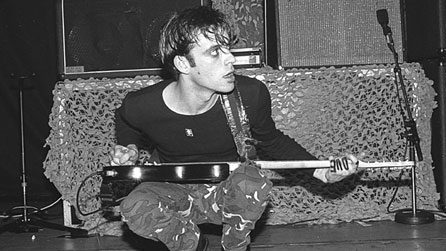

On February 1, 1995, Richard James Edwards, aka Richey James (like Rusty James in the pantheon of existential heroes) and Richey Manic, lyricist, clothes horse, Minister of Propaganda and (arguably) guitarist with the Manic Street Preachers, famously disappeared without giving any clue to his location or motivation for leaving.

February 1, 2020 sees the 25th anniversary of Richey’s disappearance. But rather than wallow in the mire of the details surrounding the disappearance—something that understandably still strongly impacts on his family (and something that we’re unlikely to receive a definite conclusion on anyway)—I want to celebrate what made Richey such a unique figure in popular music and, apart from the disappearance, why he is still a figure of such fascination for so many people, myself included.

A working-class autodidact from Blackwood, a mining town in South Wales, he gave hope to people like myself who felt isolated from their own backgrounds by their love of literature, ideas and politics. I would come to realise later that working-class culture is a lot more complicated than that, but as an alienated teen, I needed the inspiration. His intimidatingly wide and varied reading (he was said to be reading six books a week by 1994) was demonstrated in quotes used to illustrate lyrics on album sleeves and setlists. It introduced me to such wonderful, brave writing as that of Camus, Kafka, Sylvia Plath, Philip Larkin, Harold Pinter and Octave Mirbeau. A door was opened, and a world of ideas spilled out before me. Rock music became my secondary education and Richey was my favourite teacher.

Treating rock music as an equal art form with equal potential for intelligence as literature, theatre and film, without losing its populist appeal, excitement or form (a technique known as ‘entryism’), his lyrics began as a cut and paste of Beat Generation stream of consciousness and tabloid sloganeering and became multiple-sourced, richly researched cultural and political dissertations, condensed in the flame of the form of the rock song and made streamlined and solid as tungsten. To see Richey’s typewritten pages from this time, you could equally believe you were reading experimental prose or free verse poetry; such is the high volume of ideas and the lack of regard for rhyme, metre or rhythm. As best friend and bandmate Nicky Wire stated, “He wasn’t looking for an Ivor Novello, was he, the boy? He was looking for a Pulitzer Prize…he just wanted to be J.G. Ballard.”

Such ambition, intellect and creativity should be celebrated. The Manics have often made a point of separating Richey the artist from Richey, the myth of the tortured artist, and I aim to do the same here on the 25th anniversary of his disappearance. It’s not always easy to do so, as any writing can lend itself to its writer’s introspections, but certainly, the artistry still shines through.

So, in celebration of one of the greatest and perhaps most underrated legitimate artists in the pantheon of rock music, I present to you, dear reader, some of my favourite Richey writings and moments.

I eat and I dress and I wash and I still can say thank you / Puking / Shaking / Sinking / I still stand for old ladies / Can’t shout / Can’t scream / Hurt myself to get pain out (from “Yes,” 1994)

From the opener to arguably the Manics’ greatest album, 1994’s The Holy Bible, the chorus from “Yes,” a song equating prostitution with the idea of prostituting yourself in other ways—by being in a band for example and allowing yourself to be exploited by the accompanying media—offers one of the most concise descriptions of internalising mental pain or illness and presenting an image of ‘normalcy’ to the outside world as a coping mechanism. As someone with my own, ‘mild’, mental health issues, I can relate to being able to function and generally keep to my commitments and keep to a routine and go about my everyday life. I can relate to the internal clawing of my emotions by my internal chemistry as I go about these things and the anxiety that simmers just under the surface, undetected by the public. The mundanity of imagery of standing for old ladies on the bus perfectly demonstrates that ability to function in the everyday, while inside…

“You know how Catholics always hate every other religion, or Baptists hate Methodists more than they hate the Devil? Well, we will always hate Slowdive more than we hate Adolf Hitler.”

The Manics were known for their vitriol early on, but not necessarily for their sense of humour. Here, Richey’s disdain for shoegaze’s drifting, apolitical ambient noise finds perfect expression in one of his most vicious, over-exaggerated put-downs ever. Apparently, quite a few bands wanted to fight the Manics in the early ’90s. It’s no surprise after perfectly formed verbal grenades like this.

Oh the joy, me and Stephen Hawking, we laugh / We missed the sex revolution when we failed the physical (from “Me and Stephen Hawking,” 2009)

The Manics’ 2009 album Journal For Plague Lovers was made up entirely of lyrics Richey left for the band just before he disappeared. The new lyrics intriguingly seem to be less angry than the lyrics written for the previous album Richey had written for, The Holy Bible. They also have some surprising and refreshingly humorous lines, such as this one. On a track referencing everything from genetic engineering’s threat to humanity, to Giant Haystacks wrestling in Bombay, to—in unused lines—“plastic surgery for pubic hair” and the “Queen Mother stuffed for exhibition,” perhaps one of the most surprising, and most amusing, is Richey’s comparison of himself with Stephen Hawking to suggest that he physically wasn’t cut out for the sexual act. A tasteful image? No, not by a longshot. But an arresting and entertaining image in itself? Absolutely.

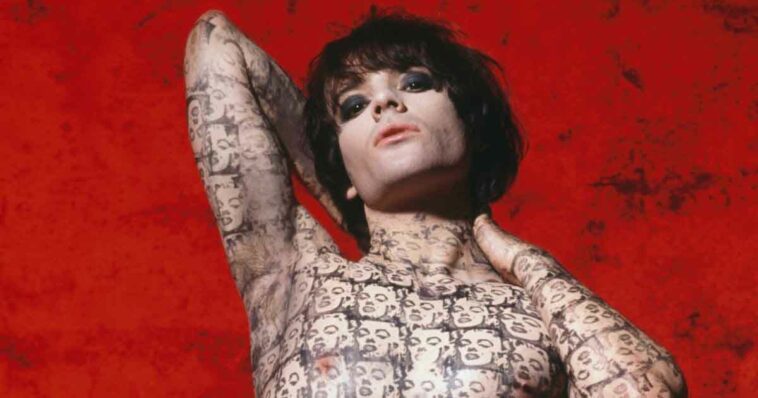

I am an architect / They call me a butcher / I am a pioneer / They call me primitive / I am purity / They call me perverted…I know I believe in nothing / But it is my nothing (from “Faster,” 1994)

It’s one of the great self-manifestos wrapped inside a mantra of opposition, and one of the most astonishingly direct assertions on the rights of the individual as to be found in pop and rock music ever. Defining himself in opposition to how his detractors describe him, his references to himself as an architect, a pioneer and purity suggested a high-functioning ego indulging in a delusion of grandeur before the inevitable crash, something we know was sadly a reality. I always assumed his references to being a pioneer were in his high art approach to his lyrics, and purity a reference to his fascination with puritanism (he couldn’t decide ultimately if he was a puritan or not, but the concept obsessed him). But architect is a bit unclear. The opposite given—a butcher—is usually taken as a reference to his self-harm. How could he be perceived as an architect in this respect? It’s still unclear to me, but the language and blunt declarative force of his proclamations here remake his conflicts as poetry.

By 1994, Richey was questioning everything, looking for worth and meaning in everything and finding it nowhere. “I know I believe in nothing” is the nihilistic summary and admission to self of this process. But at the time of writing “Faster,” Richey was not in the mood for people’s pity. “But it is MY nothing,” he spits, affirming the right of the individual to believe in nothing if that is their conclusion. Strangely terrifying and life-affirming at the same time, never had an assertion of self been so powerful in rock music before.

I would prefer no choice / One bread, one food, one milk, one food, that’s all / I’m confused, I only want one truth / I really don’t mind being lied to (from “All Is Vanity,” 2009)

For a confused, anxious mind, one that cannot discern any concrete truths in the world, the idea of having one truth to focus on, to cling to as a way of making sense of the world, is highly attractive. To suggest that to accept such a truth, even if it was a lie, betrays a sadness and desperation at the heart of the desire to rid oneself of such confusion. Richey nails such desperation here in clear, concise lines that paint a picture of someone so overwhelmed by the many, many consumerist options available in the capitalist world that they would rather be reduced to a quasi-communistic state where there is no choice, and everything is decided for them. Such longing may seem reductive, resigning oneself to the erasure of individualism, but for Richey, it was about reducing the overload of choice that made straight thought impossible. One man’s Communism is another man’s safe space; it would appear.

Regained your self-control / and regained your self-esteem / and blind your success inspires / and analyse, despise and scrutinise / never knowing what you hoped for / and safe and warm / but life is so silent / for the victims who have no speech / and their shapeless, guilty remorse / obliterates your meaning / obliterates your meaning / obliterates your meaning (from “Mausoleum,” 1994)

Never had a middle eight in a rock song been so articulate before, so precise in its language and so judgemental too. Richey was aflame with fury at the time with popular historians of the time who were releasing books that argued that the holocaust of World War Two didn’t happen or was at least greatly exaggerated. Rightly angered by such harmful nonsense, Richey wrote not one but two songs about the holocaust for The Holy Bible. The first song, “Mausoleum,” contained this damning indictment of everyone who got to live some form of everyday, normal life after the war. And that the mere fact of the dead, the victims of the gas chambers, the enormity of such barbarity, is enough to obliterate any importance or meaning we attach to our own lives. An existentialist crisis is all well and good for example, but how can you feel such despair in the face of what the victims of the holocaust suffered? This is a sobering piece of writing that never fails to put me in my place.

Shards oh chards / the androgyny fails / Odalisque by Ingres / extra bones for sale / Born-a-graphic vs. Pornographic (from “Pretension/Repulsion,” 2009)

Demonstrating Richey’s uncanny ability to apply a historical story he found through his reading, however obscure, and then apply this story to (then) contemporary culture, linking the relevance across time in exciting ways through his lyrics.

The above chorus, from “Pretension/Repulsion,” is a prime example. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ 1814 painting Grande Odalisque infamously depicted a concubine in what was said to be an unrealistic anatomical state. Ingres was said to have “favoured long lines to convey curvature and sensuality,” while also adding in supposedly five extra vertebrae than was normal.

While the controversy then lay in the fact that Ingres was engaging in subtle sensual fantasy as opposed to accurate representation and imitation of form, as it was argued painting was supposed to do, Richey Edwards was able to see in the story that arguments about body modification and representation had not changed in the 180 years since the painting was made. As James Dean Bradfield put it, Richey, writing this in 1994, was saying “how long have we been having this argument for…I suppose it would have been [magazines like] Loaded and FHM that captured his imagination as to the objectification of beauty et cetera, but he was just saying, this has actually been going on for a long time. Ingres was actually inserting an extra disc in the spine, just to idealise the woman’s body. People have always been obsessed with it.”

Since Richey’s disappearance, the argument of female representation and objectification has become even more prominent, and it has taken extremely dark moments like the actions of Harvey Weinstein for women to gain the confidence to speak out, the #MeToo movement demanding new, positive representation out of their shared trauma. Furthermore, the arguments over female representation have now moved on to the question of gender identity and transgender people, where people, unfairly, argue to deny people the choice to modify or transcend their bodies in the name of ‘accurate labelling.’ Men must be men and women must be women. The androgyny fails, indeed.

It takes a true artist to see the patterns in history and to connect the dots in such a way that its language excites in the reader (or listener) the desire for debate and to ask further questions. Richey saw the past. And uncannily, he was able to make the links that show us the future. A terrifying future, yes. But a future that is unnervingly coming to life before our eyes.

And if nothing else, “Born-a-graphic vs. Pornographic” is a hell of a line.

What are your favourite Richey moments? Let us know in the comments and share in the celebration of one of rock’s great artists!

Do you think Richey might be a transgender woman now?

No, he’s a corpse.

“I am an architect/they call me a butcher.” I always interpreted this as a marriage of (in)convenience of diametrically opposed elements. Architects are creative, they draw plans (poems/meanings/stories) for things that will be built in the future. Butchers hack and (self) gouge and cut and destroy meat, and are destructive. This interpretation fits in with the lines after. To me, that is. Shrug.