The new documentary Sisters with Transistors (directed by Lisa Rovner) is a portrait of resilience, invention, and creativity. The film is about women that found their own way through the world of electronic music, despite rejection at almost every turn. They were told that women couldn’t be composers, that their music wasn’t music, that they weren’t part of the counterculture because they used computers, and so on. The film presents a series of profiles of several women that were foundational to the development of electronic music, from early theremin virtuoso Clara Rockman and avant-garde legend Pauline Oliveros to Dr. Who theme composer Delia Derbyshire, commercial composer Suzanne Ciani and beyond. These were composers that weren’t working within what we would now consider electronica or EDM, but rather were on the vanguard of a new form of music decades before their more mainstream descendants.

Oftentimes the composers would have to take matters into their own hands and build the tools they needed themselves because the resources they needed didn’t exist or weren’t available to them. For example, when Spiegel was no longer able to compose at Bell Labs, she developed her own software to continue composing the music she wanted to make. The composers profiled were often not only the first women to reach a milestone, in many cases they were the first people to do it period, like Bebe Baron, who co-composed the first-ever fully electronic film score.

Rovner posits that these composers weren’t only innovators, but that they were revolutionaries who used electronic music as a way around classical music’s gatekeepers. “Technology is a tremendous liberator. It blows up power structures,” says composer Laurie Spiegel in the documentary, “Women are naturally drawn to electronic music. You didn’t have to be accepted by any of the male-dominated resources: the radio stations, the record companies, the concert hall venues, the funding organizations. You could make something with electronics, and you could present music directly to the audience, and that gives you tremendous freedom.”

There is another aspect of electronic music that I think shines through each composer profiled in Sisters with Transistors, and that is that the composer has complete control over the sounds and interpretation of their works. Any sound, tempo, timbre, or articulation a composer wanted was at their disposal, and unlike symphonic or chamber music which changed during each performance due to the whims of the performers, each performance could be identical. As Ciani says, “With this new technology, you could do it all yourself. So you were the composer, you were the performer, you were the sole arbiter of your creation.” The complete control inherent in electronic music composition fed into these composers already necessarily uncompromising natures. When describing Wendy Carlos’ album Switched on Bach, musician Ramona Gonzales says that “The transgressive act of recontextualizing these classic Western art music tropes, that takes a lot of strength, humor, and vision.” Gonzales’ view of Switched on Bach can apply to all of the musicians profiled in Sisters with Transistors—it had to have taken great strength, humor, and vision for these composers to navigate the male-dominated and misogystic spaces of classical and experimental music.

The revolutionary nature of many of the composers was the direct result of different ways of viewing not only music but the world as a whole. A common thread between the women was an affinity for finding music within what would usually be considered non-musical sounds during their formative years: for Delia Derbyshire it was the air raid sirens during The Blitz, for Eliane Radigue it was the planes at a nearby airport, and for Pauline Oliveros, it was the sound of the motor of her parents’ car.

Throughout the film, music is almost omnipresent, almost to the point where it is the real star of the show. At times pointillist, at others droning, some lyrical and some harsh, some serene and some room-shakingly loud. I would go as far as to say that it played more of a part in the film than narrator Laurie Anderson, even though I genuinely adore Anderson (while she isn’t profiled in the documentary, she has almost as much of a claim to be as any of the composers that were actually included). But looking back on the film, it’s the use of music that I’ll remember the most. At times it threatens to overwhelm the dialogue, but it all still feels so fresh and vibrant that it is never obtrusive or unwanted.

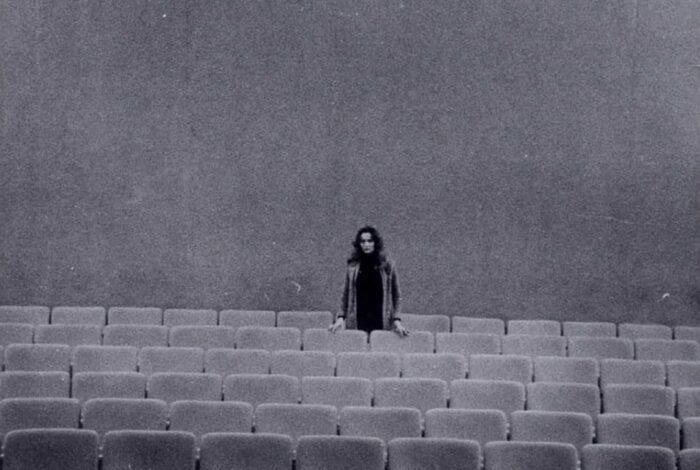

The documentary’s images are equally striking, combining new footage, archival footage, and photographs with more avant-garde footage, generally the experimental films that the music so often accompanied. Despite the disparate sources of the images, the editing provides the film with a visual style that fantastically complements the music that they are accompanying.

If I have one complaint, it’s that Wendy Carlos is only barely profiled. Carlos not only pioneered electronic music and introduced it to mainstream audiences like few before her, but she was also a pioneering member of the trans community. It seems weird to me that she receives less than three minutes of discussion and then never gets mentioned again. At the time of this writing, Carlos isn’t even included on the list of pioneers on the Sisters with Transistors website, and the only substantial footage of Carlos included is from before her transition. Carlos’ profile ends with a soundbite of Suzanne Ciani sort of dismissing Carlos’ work. Later in the documentary, Ciani claims to be the first woman to compose a Hollywood film, which isn’t true without the qualifier “solo,” which the documentary doesn’t include. The way Ciani’s accomplishment is portrayed in the film seemingly ignores the accomplishments of Carlos, whose film work isn’t mentioned at all, and Bebe Barron, whose score to Forbidden Planet was covered earlier in the film. Perhaps the filmmakers wanted to spend more time highlighting the more “forgotten” pioneers instead of someone that is likely the first person that comes to mind when thinking about female electronic music composers, but it still seems weird to me.

I also think that Rovner could have done more to demonstrate the lasting impact and legacy of these composers. While portraits of artists are compelling within themselves and there are some younger composers like Sarah Davachi who speak about the impact of the older generation, it might have been interesting to show how the sounds that these women pioneered are still very relevant in both avant-garde and popular music. The absence of these scenes is ably filled by showing that the surviving composers are still living their lives the way they want to and creating music.

Despite these few complaints, the documentary is as invigorating as the music and composers it highlights. Most importantly, it brings these composers and their music to the forefront, preserving their legacies and their words while the few that are still alive are able to be documented. If the visibility of women electronic music composers is “two steps forward, one step back,” as Ciani maintains, Sisters with Transistors represents two large steps forward for the composers it depicts.