On February 16, 1989 (which may or may not be the right year) at 10:10am, Phillip Jeffries both did and did not pop into the FBI office in Philadelphia. Cooper was worried about that morning because of a dream he’d told Gordon Cole about. We never learn what that dream was or if it pertained to Jeffries in any way, though we might infer from Dale’s actions that it did.

It’s an almost throwaway line, or at least one without any context, but its impact was indelible from the get-go, in large part due to the performance of David Bowie and the fact that this was David Bowie:

Well, now… I’m not gonna talk about Judy. In fact, we’re not gonna talk about Judy at all, we’re gonna keep her out of it.

Much has been made of how Fire Walk With Me wasn’t properly appreciated when it was released, but it also can’t be denied that the film garnered a cult following virtually from the beginning, and throughout the 1990s. And of course the same could be said for Twin Peaks as a whole—the critical acclaim is one thing, but it’s really the cult following that makes it stand out.

And what’s clear is that when Lynch and Frost decided to return to Twin Peaks 25 years later (give or take), they did so with a love for that cult following, or as a part of it themselves. Casual viewers who enjoyed the quirky characters and pie but wished the whole thing made more sense were surely disappointed by The Return, as if anything after 18 hours of Twin Peaks Season 3 the whole thing makes less sense. But that’s OK. It’s wonderful even, because it’s what does not make sense that makes Twin Peaks so infinitely rich.

And there was a whole lot of talking about Judy.

Twin Peaks is a text that keeps giving, and cannot stop giving because it’s full of small standout moments that don’t seem to connect to anything else directly, signs that beg to be imbued with significance, and pieces that don’t fit.

Twin Peaks explained?

Hell god baby damn no! I’ve found something.

There is always a sticky point to any interpretation, some kind of stumbling block to its total coherence, and my suggestion is that this is intentional when it comes to Twin Peaks and, as the kids say, not a bug but a feature.

At the same time, however, Frost and Lynch consistently undermine any attempt to appeal to their intent. The Secret History of Twin Peaks and Final Dossier are inconsistent with the reality of the show, with details sometimes but not always opposite from what we’ve seen, and indeed the text of the show subverts itself, with small differences between repetitions and narrative short circuits.

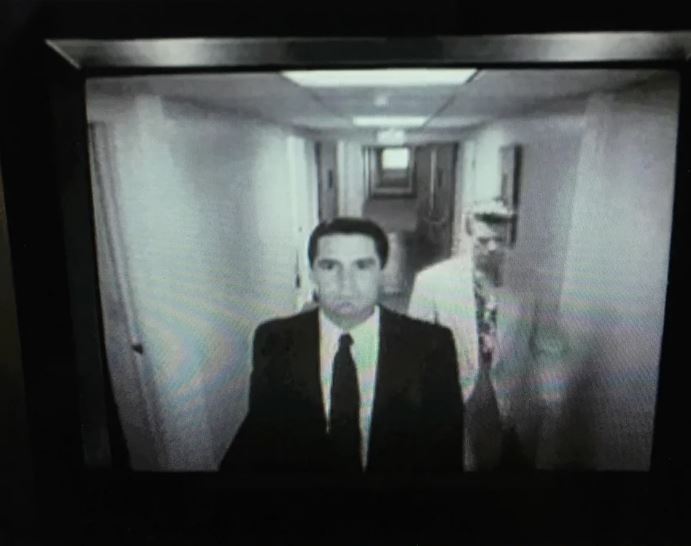

This is all there in the Jeffries scene in Fire Walk With Me itself, as its most terrifying image is perhaps in the utterly mundane CCTV footage of Jeffries walking up the hallway behind Cooper, because we’ve just seen him not do that when Cooper was actually in the hall. And of course when the scene replays in The Return, the word ‘this’ becomes ‘that’—one indexical for another, and a minimal difference in meaning, but that doesn’t stop us from reading into it.

Nathan Frizell’s voice replaces Bowie’s, and there is no narrative reason for this unless we posit one. Apparently Bowie didn’t want them to use his voice, but he died so he can’t speak for himself on the matter, and even if this is true it just drops into the bucket with all of the other “happy accidents” that populate the world of Twin Peaks. Maybe some things were mistakes at first, but Season 3 doubles down on this and even calls our attention to such things when there is no reason to do so.

The Access Guide gives James Hurley’s birthday as January 1.

I Feel Like I Know Her But Sometimes My Arms Bend Back

Twin Peaks is fully of doubles and things that don’t line up. How many other shows have so many characters that share a name? Bob and Bobby, Phillip and Phillip (or is it Philip?), and speaking of Gerard how do we make sense of him yelling at Leland at the intersection then being a meek shoe salesman again within a week or so? Or how long was he a shoe salesman and whatever happened to that aspect of this character?

The Twin Peaks High School football team apparently holds practices in February.

There are lines of flight all over the place, seeping out from the territory we think we know and at the same time offering to ignite a train of thought that could lead to a reassessment of the whole. You can’t deconstruct Twin Peaks in the Derridean sense, because it constantly deconstructs itself.

One might, nonetheless, fruitfully bring the work of Jacques Derrida to bear on Twin Peaks, and indeed that’s what I’m up to here. To deconstruct the text would be to show how what it takes to be essential relies on what it holds to be inessential, or how the details of its logic undermine the expressed intent of the author. But, again, Twin Peaks does this to itself, and the authors of Twin Peaks clearly ascribe to the death of the author, so this is more about suggesting an affinity of spirit between what’s going on in Twin Peaks and what our friend Jacques was after, beginning with his contention that the history of (Western) thought is cut through with phallogocentrism.

– I even got the frame

The reference to the phallus here might be off-putting to those not familiar with the notion as it features in (Lacanian) psychoanalysis, and may even be off-putting to those who are familiar with that, but the first and most important point is that the phallus is not the penis. It’s a signifier, or for the moment let’s just say a symbol, of a particularly masculine virility, but Jacques Lacan’s point would be precisely that men don’t possess it. No one possesses the phallus; it’s an object of desire that stitches together the fabric of meaning.

Everyone wants the phallus but no one can have it, basically. Sometimes people might think they have it, or think someone else has it, but they’re wrong. You can’t ever get what you want, because desire circulates around its lack. The phallus would be a fullness, and it doesn’t exist. And to be clear, if you don’t like the idea that meaning depends on the phallus, Derrida and I agree!

But perhaps let’s put the phallus to the side for a moment, as with ‘phallogocentrism’ Derrida is inflecting logocentrism, which is about the primacy of the word taken as a locus of meaning.

In the beginning was the Word [logos], and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. (John 1:1)

(ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος)

What an odd thing to say! One might as well say that in the beginning was the phallus. And indeed, to attempt to avoid straying too far into the weeds, let me just say that this is basically Derrida’s point. But we have to note that logos is not just the word in the sense of a unit of language, it is also the root of ‘logic’ and carries with it the sense of reason.

There is a long tradition of aligning reason, and the positive, with the masculine. God the creator is conceived as masculine not because anyone thinks God has a penis, but in line with the thought of God as possessing the phallus—that which gives meaning, and is positive precisely in the sense that it posits.

The overall picture that comes into view is one of Being (and thus of knowledge) as determinate. Everything is in its right place and everything has a reason for being the way it is rather than otherwise. But of course this view of the cosmos precisely ignores the bubbling chaos underneath it even as it acknowledges it as the negative.

In Plato’s Timaeus we have the chôra that prefigures the creation of the universe; a receptacle for what the demiurge posits. If the masculine is the positive, the feminine is negative, but this is to simply not think the feminine at all. File it under Other, woman as not-man.

Thus if Derrida takes the side of the feminine we should by no means take this to be asserting a gender binary or holding to any kind of essentialism. Essentialism is is an illusion of the phallus. We need to take the side of the inessential, which requires finding a way to think it other than as not-essential. How do we think difference without subordinating it to a preconceived notion of identity?

If we look to linguistic theory, or semiotics, we find the idea in the structuralist tradition that language consists of signifiers, with meaning depending on what they signify (signifier/signified). For example, when I mention to you ‘banana bread’ that’s a signifier, which you understand by relating it to the determinate concept you have of banana bread (the signified). Thus you grasp the meaning of what I’ve said. Perhaps I am referring to this banana bread right here that we are eating together, if you like, to keep it simple.

But the post-structuralist point Derrida would make is that it is precisely never simple. There is always a difference between your concept of banana bread and mine, or worse between my concept now and my concept previously, and so on. Meaning is always deferred, as we never really get to the signified that would provide a true resting place for it. The signified is rather always another signifier.

This is the key Derridean notion of différance, which plays on the French for both difference and deferral (and is an intentional misspelling of the former). There is a critique of the traditional privileging of speech over writing embedded in the term itself, in that you can’t hear the difference between différance and différence (in French), and there is something here to note for what follows about Twin Peaks: there is a tendency to think the truth lies in what we can see and hear, and our theories are attempts to make things sensible.

But meaning is always deferred; this is the point. The meaning of one word can only be expressed through another, or one symbol used to elucidate another. It’s always both difference and deferral, signifiers pointing to other signifiers without resting place.

This leads to aporia, or a space of indeterminacy, where phallogocentrism wants to be apodictic and to claim determinate certainty. Which it does! Just look at human history, or talk to some people. But that structure is not neutral; it’s always-already infused with a power dynamic that privileges the rational, the sensible, the simple, etc. over the complex or the ambiguous. And at its root is always a sort of groundless ground.

In the beginning was the phallus. What was before the beginning?

The primordial feminine, not defined by relation to the masculine, but precisely as this ungrounding ground—a tulmultuous yet fertile soil beneath the base of the tree of knowledge.

I want to suggest that ‘Judy’ in Twin Peaks signifies the primordial feminine precisely through its indeterminacy. It’s a mistake to reduce Judy by asking which particular person, or entity, is Judy, as much as we are tempted to do so. Judy is a multiplicity.

In talking about Judy, Cole (Lynch) says the ancient name was Jowday (as it’s spelled in the captions), but over time it became Judy. In the Final Dossier, Tammy (through Frost) renders it Joudy. It’s easy to think the subtitling was a mistake, as it was at the end of Part 7 with Bing instead of Billy, but that’s no fun.

The difference is clear in writing, but glossed over in speech, and indeed Gordon Cole calls attention to a certain movement of reduction and making familiar involved in saying “Judy” in the first place. Maybe we’re not talking about one thing, though in talking about it we can’t help but render it in terms of some entity. It’s a quirk of grammar, like the ‘it’ that is raining.

We can’t talk about Judy because in doing so we pin her down, treating a force or process as if it were a thing, and we can’t help it due to the structures of language themselves. Judy is a multiplicity—this means neither one nor many (insofar as you’re thinking of many ones). Try to think a manifold without unity. Try to talk about it. Immediately the force starts to sound like an entity.

We can’t talk about Judy because of phallogocentrism.

Watch Out For My Cousin

Let’s look at the things that don’t line up, and how people attempt to make them line up.

Jeffries says we’re not going to talk about Judy, so of course we wonder who Judy is, thinking that Judy is some particular person perhaps, but we have no point of reference. The monkey saying Judy at the end of the film is no help. Neither are the indications that at one point there was some thought of Judy being Josie’s sister (though feel free to run with that if it takes you somewhere). There is actually so little to go on prior to Season 3 that it is almost surprising that Judy is so prominently mentioned in The Return. We might think about Major Briggs mentioning Judy Garland and start thinking about the Wizard of Oz, but things aren’t getting more determinate. These are those lines of flight I was mentioning before. Take one up if it inspires you.

Twin Peaks Season 3 doesn’t provide answers to our burning questions, and neither do the books written by Mark Frost. Instead, Lynch and Frost double down on the indeterminacy. There are obvious examples of this, like the differences between Diane’s text messages or the question of what happened when Ben Horne reenacted the Civil War, but we’re supposed to be talking about Judy…

TOP: Twin Peaks: The Return

BOTTOM: The Wizard of Oz pic.twitter.com/xVan0woXGn— CinemaGrids (@CinemaGrids) January 4, 2019

Let’s take the next part backwards because if I do aim to deconstruct anything in this essay it is not Twin Peaks but in our theories about Twin Peaks. To understand things we aim to synthesize information, bring it together, and reduce differences. And we’re also prone to jump to certain conclusions. We want an explanation (because of phallogocentrism), but a close reading of the text undermines a lot of what many seem to think they know about Judy.

Take first the idea that The Final Dossier confirms that Sarah Palmer is Judy. It does not. It merely mentions her middle name being Judith. Equally, the text does not confirm that Sarah was the girl we saw in Part 8 of The Return; it merely mentions her being hospitalized as a child and says some suggestive things to help us jump to that conclusion. This is besides the fact that The Final Dossier is presented as Tammy’s report, which should at least make us wonder whether we have a reliable narrator.

Similarly, and maybe even more importantly in my mind if we’re going to talk about Judy, the vomiting being in the sky in Part 8 is nowhere in the text directly referred to as Mother. The credits say Experiment, with the one in the box in New York as Experiment Model. Yet many jumped to not only conclude an equivalence between the Experiment and Experiment Model but between both as the mother the American Girl warns Cooper about in Part 3. If you watched Geoffrey Ciani’s Wow Lynch Wow! videos, for example, he’d refer to the being in Part 8 as “the mother of all evil” so consistently you might almost think Twin Peaks itself did that.

You might think I’m being pedantic, and maybe I am, but please trust that I’m going somewhere with all of this, and the point is by no means to demean anyone’s interpretation of Twin Peaks. It’s to hopefully call attention to how we can let certain concepts about Twin Peaks settle into place such that we take them for granted. And the show feeds into that, but also undermines it.

I’ll give you another example: Virtually everyone will refer to the Red Room as the (Black) Lodge, but we don’t know that. The Arm calls it the waiting room. Maybe we’ve never seen a Lodge in Twin Peaks. Maybe they don’t even exist. How much weight should we give to what Windom Earle says about the whole thing? Hawk says things too, of course, and we surely trust him more than Windom, but the point is that each is offering an interpretation, or better an interpretation of an interpretation. It’s interpretations all the way down.

Regardless, back to Judy. Before he travels back to the night Laura died, Jeffries tells Dale that this is where he’ll find Judy. So is Laura Judy? No, but perhaps she was that evening exemplifying the primordial feminine. And perhaps Sarah was, too, when she killed that guy at the bar. And, sure the Experiment is Judy and so is the Experiment Model and so is my mother who’s coming.

Judy is a multiplicity. She presents herself as evil from the point of view of phallogocentrism insofar as it can only think the one and the many, not the disparate multiple. Symbolically, we see her unleashed through the division of the indivisible (the splitting of the atom). The experiment, a straying of the logos through its hubris into the chaos underneath, unleashing something it cannot control.

Gordon Cole calls her an “extreme negative force,” which aligns the feminine with the negative, but also fits with the idea that Judy should not be thought of as a defined entity so much as a disparate field. I’ve always liked the idea that in the pronunciation (jow-day) in Season 3 Lynch is playing on the Chinese jiāo dài, which means to explain, with the thought that explanation is precisely a levelling out of difference and nuance, but at the same time I want to align Judy with difference and nuance and not its levelling out. Perhaps Cole doesn’t know what he’s talking about, but Lynch does, or we get here an indication that ‘Judy’ itself is an ambiguous signifier, along the lines of what Derrida had to say about pharmakon.

Within the context of Twin Peaks what I think we have to recognize is that neither Cole nor Cooper knows what they are dealing with, or what they are looking for when it comes to Judy. Their perspective is caught up in phallogocentrism, which is not to say they are bad guys, because our perspective is too. Maybe Jeffries caught a proper glimpse of the chaos from its own point of view, at the cost of his own determinacy. If anything Judy is the obverse of explanation—that which cannot be explained , but might be appealed to as a signifier of the inexplicable. ‘Judy’ is an attempt to name the unnameable, to make this incoherent force coherent.

Regardless, the suggestion would be that if the goal of the Blue Rose Task Force was to find Judy, and to make Judy determinate—to understand if not contain this extreme negative force—then it was always doomed to failure. (And on my read this remained Cooper’s goal as Mr. C; he just went beyond the boundaries of the FBI.)

The right move would be beyond good and evil, beyond all binaries determined by logos, and into a free play of difference. Twin Peaks itself provides an opening to a gateway to such, if we attend to the text closely and avoid the reductive mistakes of the FBI.

It’s slippery in here.

The Mystery of the Phallotease Falcon?

“ . . . The stuff that dreams are made of”

Falcon. Tulpa?

Nice!

People always try to overexplain Judy when her unknowability is the most central aspect of the “character.”

I don’t usually get too much out of analyses where a work is described in terms of the formless emotional feminine vs. structuring logical masculine. People usually take it too far and it rarely highlights anything I wasn’t already thinking about. I think that lens works well here to point out why Twin Peaks, particularly S3, is the way it is. I’m especially weary of the gendered element of the dichotomy, but I thought the article handles that aspect quite well by explicitly limiting its scope while justifying its inclusion.

Most of my own thoughts about Judy have ended up in similar, albeit less well articulated, areas. The refusal of S3 to directly identify the experiment with Judy has always seemed important to me. I’ve had similar feelings about the Red Room vs the Black Lodge and the shifting identity of MIKE. TP is one of the only works I’ve absorbed which really allows the viewer to play around in that space of ambiguities, and that is I think the main part of the show’s appeal to me. You get to start from the point where you acknowledge that you’re getting a seemingly paradoxical superposition of equally true but ostensibly contradictory elements, and from there you work towards an understanding that’s more of a feeling than it is an answer.

Yes, and that’s what I love about it! I totally expect I’ll come back to Twin Peaks at some point in the future and be inspired to start interpreting things a new way. It’s wonderful. Glad you enjoyed the piece, thanks for reading!