Tilted “Pop Tarts and Rat Tales,” The Idol’s highly-controversial series premiere opens with a tight, claustrophobic shot of Jocelyn, played by Lily-Rose Depp. She is being directed by an unseen photographer to emote and follows his dictates (“pure sex,” “vulnerable,” “emotional”) by morphing her mien with mesmerizing accuracy. Immediately, we are welcomed into a world where the pop star serves as a professional conduit of marketable emotions—a commodified vessel of affective expression.

We are also introduced to a character who holds incredible emotional prowess. Levinson remarks on Jocelyn’s masterful and chameleonic control over her affective countenance in an HBO Featurette, which you can watch here:

“The first shot of this show I think tells you everything you need to know about Jocelyn, how gifted she is as a performer. She can laugh on cue, cry on cue. You see how good this character is at manipulating us emotionally.”

Eventually, the camera pulls away from Jocelyn, and we begin to see the crew and busybodies on the periphery, ready to adjust and tweak the details of the photo shoot (the stuffed zebra, the pill bottles, Jocelyn’s red satin robe alluding to Slim Aarons’ iconic photograph of Marilyn Monroe) for maximum effect. Amid the photographers, consultants, intimacy coordinators, and costume specialists, Jocelyn becomes increasingly drowned out by the swarming assistants—lost amid a larger marketing machine.

The red satin robe Jocelyn wears is but the first of a steady stream of pop culture references. This pastiche of references cumulatively shapes Jocelyn into a composite character—a fictionalized conglomeration of famous pop stars, divas, and actresses who’ve endured tumultuous relationships with fame and celebrity.

She wears a hospital bracelet resembling the one Selena Gomez wore on the Bad Liar album cover; she is likened to Bridget Bardot; she is compared to Britney Spears multiple times, conjuring up associations with the idol’s conservatorship drama, mental health issues, and her tabloid-fueled relationships (most notably, perhaps, being Britney’s marriage to Kevin Federline, wherein her pursuit of romantic self-liberation was viewed as synonymous with mental illness); Fiona Apple’s “Criminal” can be heard playing at the photo shoot; the nightclub where Jocelyn meets Tedros is blaring Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” (which lyrically plays out like a double entendre, conflating religious devotion with sexuality and fellatio); Jocelyn and her assistant even enjoy a late-night viewing of the femme fatale-centered erotic thriller Basic Instinct, which may be a nifty pop cultural clue (Vanity Fair believes it foreshadows the series’ ending).

Individually, these references are a bit on-the-nose. It’s not entirely uncharitable to critique the show, as a result, for trafficking in “limp clichés” (as Brian Lowry does in his CNN review). However, the miscellaneous allusions and winks arguably turn The Idol into a somewhat more welcoming brand of the Easter Egg culture we’re currently enmeshed within. By namedropping and nodding to a litany of controversial pop stars, the show reinforces how cyclical and repetitive the narratives mainstream media chooses to peddle can be. In having historical weight and symbolic resonance, I’d argue the references are more Pynchian or Joycean-esque and less the empty IP you’ll find in products like Space Jam: A New Legacy.

When compiled together, the archetypal trappings of female celebrities (specifically young female pop stars who grow up pandering to a squeaky-clean image under the spotlight) become more and more transparent. One can start to track the pathological predictability of the entire system—insofar as the media’s inhumane expectations and the repressive marketing strategies ensnaring these women push them to seek liberation. There’s a cumulative effect created—a feeling of inevitability within the entire template. Yes, the pop starlet clichés are all there—but they also exist and recur.

To show just how unfree Jocelyn is in her current stage of pop stardom, Levinson deploys a few visual tricks—some nuanced and some conspicuous. The previously mentioned opening pull-away shot of Jocelyn ends up with a stationary long shot of stagehands coming into the frame to fix her hair and props. This removed and uninterrupted shot exists in stark contrast to the close-up seconds earlier, and the startling juxtaposition is clearly intentional. When up close and intimate, we, the audience, are completely attuned to the depths of Jocelyn’s emotional malleability. Her mercurial command of the camera is spellbinding. When the camera pulls away, however, the spell dissipates and the clumsy, uncomfortable reality sinks in.

By not cutting, Levinson accentuates how Jocelyn’s emotional manipulation was quite incongruous to her immediate environment, materializing just feet away from casually chatting and disinterested parties, such as the two women in the right corner of the frame clearly albeit inaudibly conversing about something privately. Levinson’s static/wide/flat framing after zooming out is a common technique in European art-house films and cringe comedies, used to magnify situational awkwardness and signify a sense of panoramic multiplicity.

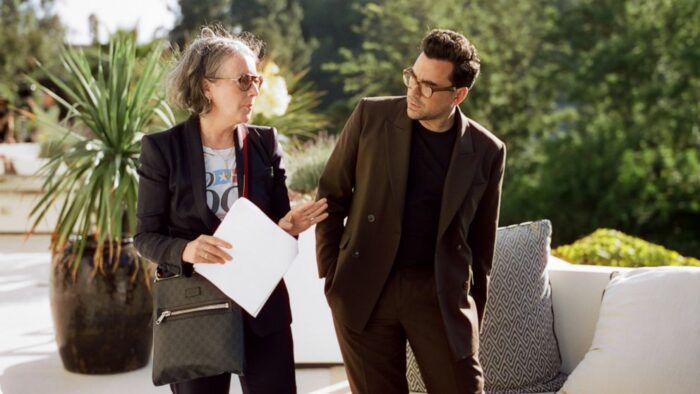

From here, Levinson’s camerawork becomes increasingly mobile and active, but it remains unnervingly distant from the subjects onscreen. Whether following Jocelyn as she rehearses dance steps for a music video or eavesdropping on the Altman-esque cacophony of overlapping chatter between industry heads trying to crisis manage a PR emergency revolving around a selfie circulating of Jocelyn with cum on her face (quite humorously, Dan Levy’s character notes that “human cumsock” is trending on Twitter), there’s a sense of voyeuristic detachment.

Levinson achieves this sense of spying by placing the camera far away from the actors and zooming both in and out or erratically panning to reinforce our remoteness. The audience is thus placed in a liminal space—granted slightly more access than the paparazzi or a shunned journalist or reporter, but nevertheless left snooping and prying. The distance between the camera and the subjects also allows the audience to take an omniscient perspective, overlooking the multifaceted dramatic narratives simultaneously unfolding.

(I personally got some serious Knight of Cups vibes here; intentional or not, the shots of Hollywood execs trying to network and handle a PR crisis around a sun-blanched portico and pool evoke the scene where Rick (Christian Bale) dazedly wanders around in a similar setting in Malick’s underrated existential undressing of the entertainment industry.)

The rapid cutting between Jocelyn—visibly exposed and symbolically beneath her publicists, record label president, etc. (all overlooking her music video rehearsals from their perch on the mansion balcony)—and her team further underlines the power discrepancy between the star and those behind the scenes pulling the strings. At the same time, the tone and pacing of the fast cuts create a darkly satirical/screwball comedy tone, which very few reviews have acknowledged despite scathingly chiding the dialogue as tone-deaf.

In fact, “Pop Tarts and Rat Tales” is very funny. When Nikki Katz (Jane Adams) equivocates to explain how mental illness is sexy (her thesis being mental health issues give Jocelyn a sense of unpredictability allowing Midwestern boys to fantasize over the slim possibility of scoring), it’s meant to be an outlandish lampooning of the industry. It is meant to be tone-deaf and cringe. When Dan Levy talks about subpoenaing Reddit or begs an unidentified outlet on the phone to remove a link to the cumshot selfie by reminding the outlet they’re feminist allies, it’s meant to be hyper-online and nauseatingly topical, like many of the Silicon Valley-focused inside jokes in Succession.

One of the more amusing examples of public cognitive dissonance surrounding The Idol thus far has been watching Gen Z try to reconcile their appreciation of Rachel Sennott with her appearance on a show they’re being told to loathe. For those who enjoy Sennott’s uniquely awkward comedic sensibilities, she gets multiple one-liners and moments to shine as Leila, Jocelyn’s assistant and close friend. From her induction of the cumshot as being irrefutably a selfie to her pedantic semantic correction of the misuse of ‘bukkake’ to her description of Tedros (Abel Tesfaye) as “rape-y,” she is in her comedic zone—chewing up each scene with crude Zoomer humor.

Perhaps the most loaded joke in the episode involves the politics surrounding the nudity rider and the intimacy coordinator trying to ensure everyone stays in compliance. Given the narrative subplot surrounding an intimacy coordinator in Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep, this emergent bureaucratic role/safety precaution is certainly on the minds of more filmmakers than just Levinson.

Of course, the irony of the imbroglio is immediately obvious and likely self-referential. Given the pushback against Levinson has been his sexualization of women, it is obviously convenient to depict an intimacy coordinator ironically stripping Jocelyn of her agency instead of reinforcing it. The interaction is yet another prime example of one of Levinson’s favorite conceits: preemptively commenting on a perceived provocation he knows he’s making, highlighting just how unwieldy and bureaucratic sexuality has become due to reactionary red tape.

In a cruel twist of circumstance, the regulatory precaution in place to protect Jocelyn from exploitation has instead deprived her of body autonomy. And due to the costs of production, the bureaucratic process for rectifying the contractual verbiage of the nudity rider becomes self-defeating—forcing Chaim (Hank Azaria) to lock the intimacy coordinator in the bathroom so that Jocelyn’s areolas can remain freely exposed and unpatrolled. Farcical as it is, the situation is indeed tricky and Levinson teases out its complexity by having the intimacy coordinator explain the pitfalls of giving Jocelyn the power to veto the contract instantly (noting that such permission would make her vulnerable to top-down manipulation, pressure, and exploitation).

This subplot parallels the concurrent frenzy of Jocelyn’s PR team trying to navigate the media whirlwind resulting from the cumshot selfie circulating online. Together, these two conflicts create a layered dialectic about the complexities of female liberty in our hyper-vigilant and constantly-monitored modern age. Due to the #MeToo movement, drastic measures have been taken to curb the toxic and predatory abuses within the entertainment industry.

Well-intentioned or not, some of these measures have had inverse effects, leaving some women unfree to embrace aspects of their sexuality. Due to preset parameters around the notion of self-empowerment, pop stars are often pressured into defining licentiousness and submissiveness solely in terms of victimization. For many female celebrities/pop stars, any digression from the dominant feminist messaging must be accounted for—micromanaged and reintegrated into a proto-feminist narrative for the sake of damage control.

A prime example of this is in the controversies surrounding Lana Del Ray, who felt compelled to write an unprompted public statement defending her lyrical motifs involving “submissive” female roles in relationships:

“I’m fed up with female writers and alt singers saying that I glamorize abuse when in reality I’m just a glamorous person singing about the realities of what we are all now seeing are very prevalent emotionally abusive relationships all over the world.”

Unfortunately, the resulting conversation quickly pivoted from Lana’s central point to a debate about white female pop stars and race. This was a foreseeable conclusion, given Lana’s tactlessly envious and loaded reference to “Doja Cat, Ariana, Camila, Cardi B, Kehlani and Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé” as enjoying “number ones with songs about being sexy, wearing no clothes, fucking, cheating,” while she remains pilloried for her beta off-brand of sexuality.

Given the prevalence of identity politics, Lana’s statement was a disaster class in unwise wording. As Ashley Reese ungenerously reflected in her Jezebel article, “The optics of Lana, a white woman, complaining about feminism lacking space for her while critiquing the acclaim allotted to several Black pop artists is mortifying.” While it was a myopic decision to use ambiguously hostile language toward Black female pop stars, Lana quickly clarified her intent:

“To be clear because I knowwww you love to twist things. I fucking love these singers and know them. #that is why I mentioned them.”

Lana’s plea was too little, too late. Whether or not the claims of racism were warranted, the unplanned controversy inadvertently deafened Lana’s primary message, which was to defend her lyrics against claims of antifeminism. And as the thesis faded into oblivion, it became somewhat obvious that few wanted to reckon with the underlying intention and complexity of Lana’s core statement on feminism in the first place.

This dismissal reflects the same sort of projectionist behavior currently tainting The Idol, both within the pilot episode and the commentary on the show, wherein the industry and public willingly ignore Depp’s endorsement of her own agency and authorization. In fact, in refuting rumors of on-set turmoil and graphic sex scenes, Lily-Rose Depp has staunchly contended that the accusations were “not reflective at all of my experience shooting the show.”

In fact, Depp claims in the same article that “bareness, physically and emotionally, was a big part of the discussions that we all had [and] decisions I was completely involved in.” So what’s really going on? Is Levinson exploiting his actresses? Is he perpetuating a dangerously oversexualized archetype of femininity? Or is the promiscuous, subversive, and sexually liberal nature of his collaborative aesthetic vision simply too dark and disquieting for mainstream audiences?

While the debates around the archetypes of feminism are clearly at the center of The Idol’s controversies, there may be another tendentious subtext touching upon the evolving racial/ethnic politics within the world of pop music. At the very least, the relationship between Jocelyn and Dyanne (played by Blackpink’s very own Jennie Kim) is geopolitically intriguing. I’m curious if Levinson and his team dare to cross-compare American and Korean pop. This potential thread remains to be seen but if the first episode’s any indication there may be some commentary already ripe for the taking.

I may be reading too much into this, but it seemed quite telling that Jocelyn is chided by her dance coach and then forced to watch Dyanne rehearse her music video sequence. Within this dynamic, Dyanne is shown as a paragon of pop music perfection—more flawless in her execution of the choreography than Jocelyn. This reflects well-known stereotypes of the lean, mean, K-Pop machine, which has been long documented as rigorously pumping out robotic pop stars.

Whether The Idol decides to show K-Pop as a paradigm of pop culture’s apotheosis or as a foreign threat to the diminishing American hegemony on the global scene or avoids commentary altogether will be something worth tracking. That said, if the amicable sauna scene (wherein Jocelyn comically smokes and declares her intent to go clubbing) is any indication, Dyanne and Jocelyn may just be colleagues/friends in the narrative, and the inclusion of a phenom K-Pop star may be nothing more than a savvy and topical casting choice to garner international attention (and perhaps metaphorically conflate the two industries).

Whatever the case, the image of Jocelyn smoking in a steamy sauna has become a Twitter meme, yet another cause for moral hysteria, and inspiration for a viral spoof video by SNL star Chloe Fineman. If you scroll through the memes, you will see that Jocelyn indeed chain smokes a steady stream of cigs throughout the episode. It’s a fairly cliché characterization but not that far-fetched. What’s more remarkable is how up-in-arms anti-cigarette sentiments are becoming.

Though most of the reactions to Jocelyn’s smoking habits were light-hearted and funny, quite a few resembled the same social media policing Jenna Ortega recently received after she was caught by the paparazzi enjoying a quick nicotine fix. It’s one thing for Ortega’s mom to publicly shame her (cigarettes can lead to bad oral hygiene and cancer, springing the maternal instinct into action); it is a bit odder for her peers and fans to be visibly outraged (given Ortega’s recent transformation into Wednesday Addams, smoking seems like a given). Once again, the panic around Ortega smoking reveals the friction between individual freedoms and corrective calls for social conscientiousness.

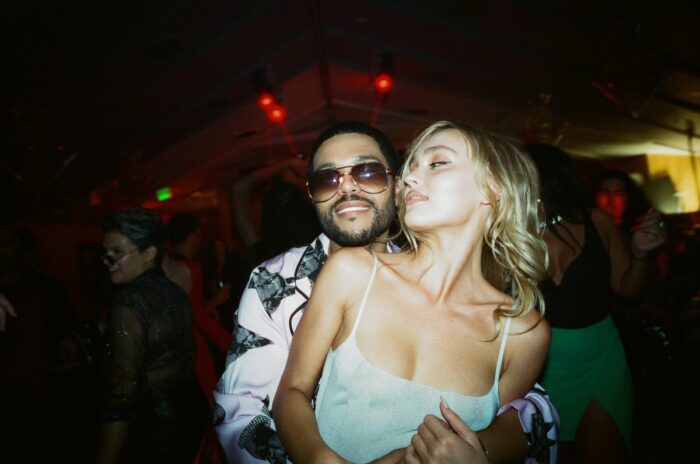

Cig breaks aside, the steamy sauna scene is soon replaced by a synth-heavy nighttime convertible joyride to a steamy dance floor (shot in a manner that nostalgically captures the scummy hipster Vice Magazine aesthetic circa 2008). The nightclub Jocelyn’s coterie rolls up to is pulsing with light, young bodies, an ominous gangster with a “Life is War” tattoo on the back of his shaved head (the sinister synth score amps up to eleven every time the camera shifts to him, signaling a foreboding subplot), and Tedros, the owner and emcee, who declares the space “a church for all you sinners.”

Fittingly, this is not the first reference to sinners—we’ve already heard numerous clips of Jocelyn’s upcoming single, “World Class Sinner,” during her dance rehearsals. It narratively makes sense that the proprietor of a space deemed as a worship destination for sinners might attract a pop star who’s self-defined as a reprobate. Tedros soon spots Jocelyn on the dance floor and demands a dance. And as explored in an Elle article, the language used here is quite revealing:

“I gotta have a dance with you. Can I dance with you? I’m gonna dance with you.”

Notice how Tedros moves from yearning and desire (“gotta”) to a formal request (“Can I…?) to an imperative statement (“I’m gonna…”). Jocelyn yields, regardless, and as the two dance we’re subjected to Tedros’ sleazy sensibilities as he woos Jocelyn with hackneyed pick-up platitudes like “you fit perfectly in my arms.” What Jocelyn sees in him we don’t quite see yet. But the same question could apply to Pamela Lee in the opening nightclub sequence of Episode 2 (“I Love You, Tommy”) of Pam & Tommy, wherein we witness the actress fall for a similar bad boy figure in a similar setting.

After dancing, the two sneak away into a stairwell to turn up the heat, while Leila frantically searches for Jocelyn, looking distraught. Even here, the sex seems to be secondary for Jocelyn. She keeps trying to discuss her single, “World Class Sinner.” It seems clear Jocelyn keenly senses a possibility for truth lurking within Tedros’ mysterious, shady persona. Sure, he rocks a terrible rattail and offers corny pick-up lines, but these signifiers are just the sort of thing pop stars like Jocelyn might look for in pursuit of an unfiltered bad-boy prototype.

These inklings are made manifest as the scene proceeds. Jocelyn and Tedros’ flirtation/foreplay revolves around their respective appreciation of timeless pop music. They both agree Prince’s “When Doves Cry” is the antithesis of pop’s superficiality before Jocelyn returns to the club to mollify her worried assistant.

Returning home, Jocelyn experiments with autoerotic asphyxiation. This is one of the three times we see her strangled: By herself, by Tedros (in the final scene), and by a swarm of male dancers performatively clenching Jocelyn’s throat as they rehearse for a music video. The symbolic asphyxiation within the choreography is the easiest to overlook, but equally suggestive: hinting at the suffocating nature of the stardom and the entertainment industry.

The next day, Jocelyn conducts her interview with the Variety reporter, Talia (Hari Nef), everyone seems to already be tiptoeing around (Nikki Katz, for one, calls her “communist China”). Talia is very seasoned at her job (she balks at an earlier description of her as a reporter, saying she’s a “profiler”), and quickly begins to pull veteran journalistic maneuvers to coax Jocelyn into spilling her intimate feelings. Multiple times, she pauses the phone recording of the interview—a showy display of intimacy—to say something presumably off-script.

Jocelyn, however, sees right through the ploy. She is not flattered by Talia’s glowing compliments on her ability to withstand the cumshot controversy (it must have required “Olympian focus to not be derailed by shame and humiliation”) nor is she as willing to summarize it in trendy narratives. Despite Talia’s nudging, Jocelyn is resistant to falsely twisting the controversy into a PR opportunity. She refuses to deem the selfie leak as revenge porn and play the victim or play the female empowerment card either. In fact, she seems to want to transcend all the power-based narratives entirely (“It’s just human I think”).

This is a novel approach for a modern pop star figure to take. Seeing herself as being baited into a no-win situation, Jocelyn becomes defensive: “When people would tell me it was important to comment on something publicly, I used to buy into it. Now I know I’m being hustled.” Talia is not willing to capitulate so easily. Sensing Jocelyn’s obduracy toward becoming a clickbait think piece, she opens a bit more, acknowledging that indeed her editors at Variety won’t accept reticence.

Switching the subject, Talia asks Jocelyn point blank: “We all have to answer to somebody. Who do you answer to?” It’s an honest comment, and one that Jocelyn deflects by pausing and smarmily stating “God.” It’s a foolproof answer and one that is impossible to interrogate. It’s also another sign that Jocelyn’s quest is for something higher and more absolute than the endlessly mutable and vapid strategizing of her contemporaries. She doesn’t want the easy out; she wants to rekindle her innermost energies with an unmediated entity, accepting its Dionysian forces and perverse complexities.

The interview also evokes Godardian snark, recalling the deeply philosophical interviews in Breathless. Given the earlier reference to Bridget Bardot, this connection doesn’t seem like such a stretch of the imagination. In fact, as sacrilegious as this may be for Godard enthusiasts, it’s not hard to see the similarities between Sam Levinson’s recent output and Godard’s early films, which were highly stylized, visually poppy, quite palatable, and filled with sarcastic, subversive, aloof, and self-reflexive jabs at the zeitgeist.

One can only wonder what kind of reception Contempt might receive if it opened in our current cultural environment. Would it be deemed too salacious? Too glib? Too self-referential and self-aggrandizing? I wouldn’t bet against it; at the same time, you can’t deny the reality that Godard’s sardonic breaking of the fourth wall was revolutionary in the ’60s in a way that it just can’t be today. Though there are similarities, Levinson can’t claim to be one of the pioneers of sprinkling autobiographical subtext into the folds of his films.

It’s easy to imagine that the confrontation between Talia and Jocelyn is largely meta, given how uncharitable Sam Levinson’s recent output has been received and how contentious negativity has informed his narratives. One of the more overt attributes of echo chambers and narrative distortion is the reverberation of specific keywords. Jocelyn is too world-weary to not see through Talia’s gambits and knows to remain reticent. Levinson clearly realizes the wisdom of strategic withdrawal in terms of interviewing, but his cynicism seems to seep out artistically again and again. Reaffirming Jocelyn’s fears about Talia’s manipulative intentions, The Idol has found itself beleaguered by an army of hypothetical hustlers spinning narratives for clicks.

At this point, the ever-shifting narratives and buzzwords around the show unveil a distinct story as they drastically morph to fit the overarching agenda. When the premade criticisms of the show—namely, that it is toxic and exploitative of the female body—could not be weaponized against the first episode, the narrative swiftly shifted. Unable to pile drive the series’ opening episode on moral terms, the critical and Twitter communities shifted to regard it as a bland, dull, boring, vain/superficial, try-hard attempt at subversion.

Any such experiential criticism is fair and subjective. One could hypothetically call Breaking Bad or Mad Men or Succession boring, and there’s nothing one can do to counter such an emotional experience. What is suspect, however, is how ubiquitously certain tailor-made terms reappear, and how hasty the hot takes are to draw emphatic conclusions.

The premiere of The Idol is barely over 50 minutes long (including the credits). It essentially consists of three sections—a photo shoot/dance rehearsal, a night out at the club, and a first meeting between our two star-crossed lovers. Yet, for countless critics and Twitter users, this 50 minutes was insufferably snore-inducing enough to write off the entire series (that is, if they were not actively protesting and boycotting it altogether).

This week, a prominent opinion columnist in the NY Times deemed it “the first big-budget TV show of our backlash era.” Expectedly, this article saw it as nothing more than a piece of red-pill artistic clickbait, claiming the show to be “interesting mostly for what it reveals about a moment when reaction is disguising itself as edgy transgression.” The column goes on to call The Idol a trap—claiming it desperately wants to be a scandal and citing the viral Rolling Stone article.

Does the show want to push buttons and ruffle feathers? No doubt. Is this novel or unartistic? Not in the least. And does The Idol want to be first and foremost recognized as an artistic work? Absolutely. The fact that Levinson responded to the Rolling Stone article by telling his wife he thinks “we’re about to have the biggest show of the summer” does not necessarily mean that he: 1) was happy to have a Rolling Stone hit piece calling the production chaotic, or 2) is privileging political disruption over aesthetic creativity. It’s not even necessarily gloating so much as the wry, off-handed steadfastness of an artist (much like Jocelyn in this episode) staying even-keeled amid public backlashes.

Meanwhile, The Weeknd (billed here under his birth name Abel Tesfaye) has also taken a critical beating, receiving spiteful eviscerations of his bad acting. Could one call Abel Tesfaye’s acting a bit stiff and stilted? Sure. Is it fair for Variety to publish an article declaring his acting skills to be nonexistent after what amounted to less than 15 minutes onscreen, including many shots where Tesfaye was shot in dimly lit settings where his eyes and costuming did most of the acting? Is it fair to pillory Tesfaye’s onscreen presence when he had less than 30 lines of dialogue and was meant to come across as icky and grating? This type of reaction seems like more than a stretch: It seems like a nefarious agenda that can spoil an entire career.

To be fair, there’s a long history of over-congratulating and over-critiquing pop stars for their debut acting performances, but to be so emphatic and declarative this early seems like a cash-grab attempt at cynical clickbait, at best.

This is not to say The Idol’s premiere is immune to criticism. Notions that the acting felt stilted and that the tropes felt too familiar are easy to back. Lauren Puckett-Pope’s recap of the premiere in Elle, to offer a concrete example, skews negatively in an honest way, providing a masterclass on how to untangle the complexity of why something could feel icky and unseemly:

The whole thing reeks of abuse, which is, of course, precisely director and co-creator Sam Levinson’s point. Right? But what if Jocelyn’s in control here? Is that even possible? And if it is, what does it mean that her artistic release can arrive only when she’s in the clenched fists of a man like Tedros? I want to believe there’s something interesting about gender and power sitting at the root of this story, but I’m concerned whatever it is—if it exists—is already getting lost in the so-called “provocative” imagery.

The article goes on to astutely explore how the nuances of the dialogue reinforce a form of linguistic power play:

“Now you can sing,” Tedros tells Jocelyn as the premiere episode draws to a close. Not, “Now you will sing,” or “Now you should sing,” but “Now you can.” Without Tedros’ intervention, what is supposedly Jocelyn’s most “believable” form of artistry is rendered an impossibility. I’m curious to see how that will be twisted into her empowerment.

By the end of her recap, Lauren Puckett-Pope’s interpretations take a vastly different direction than I personally took. She fixates on “power dynamics” and filters the interactions primarily through a lens of gender. She also claims the premise to be “so straightforward it’s aggressive,” which seems to be at odds with her earlier sentiments that the moral boundaries were being blurred to the point of inarticulateness. I found this somewhat confusing but respected her critical fidelity to the material itself, relieved to find a critic willing to charitably parse the material for what it’s worth instead of slovenly regurgitating unreflective, knee-jerk, code-word rejections.

For me, the role of gender and interpersonal power is certainly present, but it is also subordinate to the thematic focus on invoking one’s innermost, primal source of artistry. The final date at Jocelyn’s mansion nicely sets up this exploration of the intersection between artistry, sexuality, and authenticity. Yes, there are power dynamics and conspicuous BDSM overtones. But the interactions feel reciprocal. If anything, Abel is forced to play a humbling inversion of his rockstar persona in real life. Here, he is the sexual muse and the seductress—a fairly pathetic nightclub owner trying to woo a pop star who is socially out of his league.

Levinson establishes Tedros’ dual role well from the moment he arrives at Jocelyn’s palatial gates leading into her mansion. Wearing a long, black cape-like coat and shot in silhouette, he looks like a vampiric hipster. This is by design—Abel himself has acknowledged that one of the archetypal inspirations for his character was none other than Dracula himself. Is he a parasitic bloodsucker or a dependent bloodsucker? This will be interesting to follow.

Meanwhile, Jocelyn plays mind games with Tedros from the get-go, having her assistant let him in and letting him wallow (Tedros pours himself wine and sits at the piano as she puts on her heels “to be taller” than him). Clearly, she’s taking her precious time prepping herself on a zebra pelt (resembling Slim Aarons’ famous “Beauty and the Beast” (1959) photo of Marilyn Monroe on a tiger rug) as a power move. Her desires and endgame, after all, are equally if not more suspicious than Tedros’ erotic aims; whatever she’s ultimately after, it is pretty apparent Jocelyn views Tedros as a sexual conduit and a possible muse she can use to help clarify her artistic identity.

It’s quite telling that after forcing Tedros to wallow anxiously in isolation, Jocelyn immediately takes him into her studio to listen to her latest single. We’d just been exposed to her insecurities surrounding the single a few scenes earlier when she tells Leila she’s “embarrassed” and scared of making a fool of herself by releasing it (“I don’t want people to make fun of me.”). Somewhat incredulously, her assistant/confidante had consoled Jocelyn’s insecurities, unctuously calling the single “edgy.” But she stutters when she tries to further pitch her ingratiating opinion, noting “Not every song has to be, like… it’s fun you know.” Jocelyn’s unsold expression says it all. She knows Leila’s unconvincing delivery reveals her true feelings.

One gets the sense that Jocelyn is terrified she’s surrounded by a bunch of complicit yes-men/women. After all, we witnessed everyone on her team freak out about how she’d been “frosted like a pop tart” (as her record label rep, Andrew Finkelstein (Eli Roth), put it, throwing a fit), only to grovelingly accept Jocelyn’s dismissal of the severity of the crisis (anticlimactically declaring that it “feels like it could be much worse”). It’s not hard to realize how Tedros offers an antidote to this sycophantic vacuum.

After Jocelyn brings Tedros into her studio and plays the “World Class Sinner” demo, she propositions him for honest feedback. Tedros is initially positive, but Jocelyn doesn’t believe him. Inside, she wants her single to be lacerated—she knows it’s inauthentic (why else would she be desperately begging everyone around her for their opinion?) but can’t put her finger on exactly why.

Tedros gives her precisely what she really wants—harsh, uncut criticism:

“There is one problem. I don’t believe you. You should at least sing it like you know how to fuck.”

– “What makes you think I don’t know how to fuck?”

“Your vocal performance.”

Finally, Jocelyn has someone with enough gall and eccentricity to have an actual opinion. Tedros goes on, telling her she’s “gotta stop caring what people think,” because she’s “too locked up in [her] head,” and “need[s] to block out the world.” Offering a paradigm of pop music sexuality, he points to Donna Summer’s “Love to Love You Baby,” and notes, “When she sings, there’s no doubt that she knows how to fuck.” Far from upsetting Jocelyn, this criticism earns her instant adulation and trust.

Very succinctly, Tedros has just proven to Jocelyn that there is a difference between singing about sexuality and singing with sexuality. His cross-comparison to Donna Summer’s sensuality exposes the artificial qualities of crassly plastic pop songs that peddle sex (i.e., “World Class Sinner”). In a single rebuke, Tedros obliquely calls out mainstream pop for capitalizing on sex while simultaneously circumventing its actual essence. The analogy highlights the ways in which sexual content is often commodified and bereft of sentient invocations. With a simple comparison, Pedros pinpoints the artistic dilution and inauthenticity at the root of Jocelyn’s restless paranoia.

As a result, Jocelyn excitedly allows herself to be initiated by Tedros, submitting herself to him in a symbolic act of BDSM. Sure, the power dynamics are rife on the surface. But the true recipient of this interaction seems to be Jocelyn, who’s being baptismally inducted into her body by her dark, Faustian mentor. It’s fair that some feminists may flinch and recoil at the fact that Jocelyn undergoes this transformation from a sleazy authoritarian male.

There are certainly other ways to reattune to one’s raw, feral sexuality in hopes of tapping into the primordial forces of artistic feeling, but the fact remains that the setup puts Jocelyn in a symbiotic relationship. And heavy-handed or not, it’s a pretty timely commentary on the debates surrounding artistic sexualization. Ironically, Levinson is precariously placing his own hyper-sexualized canon under the microscope in pushing this message, but it still resonates nonetheless—reminding us to: 1) differentiate between sexual feeling and scandalously tawdry art/marketing; and 2) not overlook the ways in which carnal and hedonic energies have long been entwined with the decadent pleasures of art.

With Jocelyn’s explicit permission, Tedros puts a red hoodie over Jocelyn’s face in a sadomasochistic gesture (bringing to mind Little Red Riding Hood and The Wolf, for one reviewer) before cutting a slit so she can breathe. “Now you can sing,” he pronounces as Jocelyn gasps, culminating her baptismal rite of passage or (anti-)christening or whatever you want to call it. As the credits kick in, the cheekiest and most on-the-nose allusion throughout the episode emerges as “Darling Nikki” by Prince erupts.

Far from a flat or lazy reference, Prince’s banger from Purple Rain parallels the plot of the episode. Just take a look at the first two verses:

I knew a girl named Nikki

I guess you could say she was a sex fiend

I met her in a hotel lobby

Masturbating with a magazine

She said how’d you like to waste some time?

And I could not resist when I saw little Nikki grindShe took me to her castle

And I just couldn’t believe my eyes

She had so many devices

Everything that money could buy

She said sign your name on the dotted line

The lights went out and Nikki started to grindOhh Nikki

It’s hard to think of a needle drop that could be any more apropos and aligned with the storyline so far. Minor details differ, but the overall theme resembles “Pop Tarts and Rat Tales” beat-for-beat. Time will only tell where the series goes from here, but thus far, the pop culture nods seem to be well-executed. Moreover, Levinson has found a vehicle for commenting upon some primary motifs currently overshadowing his personal and artistic persona.

On every level, The Idol feels like a sadomasochistic match made in hell or heaven, depending on how you look at it. And whether the cultural power dynamics at play ultimately facilitate or sabotage the show’s fate, the emergent tensions will serve as a litmus test, giving us all some insight into where we’re heading next from our current cultural crossroads.