Aptly titled “Double Fantasy,” Episode 2 of The Idol is all about mirrors, substitutes, and double-crossing. Leaning deeper into its erotic thriller undertones, and slipping intermittently into soap opera territory, the episode ramps up the melodramatic narrative quite a bit. There are still promising signs of multilayered storytelling, but glimpses of genre artifice lurk just underneath the surface.

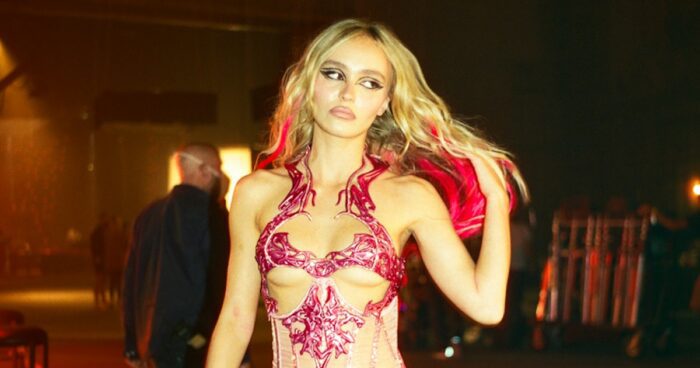

Everything kicks off with Jocelyn (Lily-Rose Depp) calling her team together to listen to a new edit of “World Class Sinner,” which is filled with hyper-sexualized moans that resemble the moans in Donna Summer’s “Love to Love You Baby” (which cannily plays over the credits). The song is arguably overproduced now—oddly, instead of stripping down the artifice in search of authenticity, Jocelyn amps it (the first sign of many that my excitement about the premiere’s thematic interest in aesthetic principles were overblown and misguided).

On the other hand, the song feels a bit more edgy and contemporary. The newly distorted vocalizations, for example, sound like hyperpop alterations deployed by the likes of Sophie or Charlie XCX. In all honesty, if the moans were dialed down just a few decibels, the remix would sound remarkably more vogueish than the original version. Nevertheless, Nikki (Jane Adams), donning a villainous red dress, is not having any of it and uses her disdain for the remix to spell out Jocelyn’s fallout in a detailed exposition dump.

Chronicling her canceled tour and mental health issues, including a fugue/psychotic episode where Jocelyn was found babbling things about outer space, Nikki shuts down Jocelyn in a peremptory tirade, furious that the “princess” would dare think she had a “bigger dick” than her PR team. Throughout, Nikki’s lexicon is filled with gender-loaded signifiers and reeks of patriarchal authority, claiming the extent the label went to recruit a team of producers to help Jocelyn record an EP filled with “giant f***ing big-t*tted hits.”

Playing Nikki on the verge of caricature, Jane Adams is clearly having a blast chewing through her scenes as an abusive manager figure with zero filter or compassion for Jocelyn’s current fragility. I was personally annoyed, however, by the debate over the remix in theory. Clearly, in the age of Spotify, the label could have easily placated Jocelyn by pushing the original single in the initial release and releasing the remix down the line. Problem solved: this simple marketing strategy would have easily reconciled the entire face-off with minimal to no downsides.

At the same time, Nikki’s bloated broadside rings true to her character. It also serves as a convenient way to characterize the polarizing dynamics of Jocelyn’s team. Leia (Rachel Sennott) unconvincingly thinks the remix sounds good; Xander (Troy Sivan) and Destiny (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) seem somewhat supportive if not a bit uncertain or indifferent; Chaim (Hank Azaria) agrees with Nikki on the entrepreneurial side of things, but he vehemently disagrees with her blunt insensitivity and political rhetoric, ironically retorting, “Who wouldn’t be grateful after that haranguing?” after Nikki complains about Jocelyn’s ungratefulness.

Inverting the standard gender archetypes ever so slightly, we immediately learn the truly vicious managerial figure is Nikki, not Chaim. In fact, Chaim is depicted with a refreshing degree of avuncular tenderness as Azaria shines (turgid Israeli accent or not) during a few intimate bedside conversations with Jocelyn, showering her with the kind of positive reinforcement she so desperately needs: “You know what I believe in? You. 100%.”

Chaim may be responsible for maintaining the business side of things, but he balances the duality quite well. This dichotomy is illustrated beautifully after the disastrous music video. After venting about his struggles and anxieties about keeping Jocelyn’s media empire afloat should she continue to fail to put out commercially viable music or tour successfully (“At the end of the day, it’s not what you say. It’s what you do. It’s what you sing…”), he chides himself out loud for sounding so aggressive and mercenary (“I told myself I wasn’t going to lecture you and here I am.”).

From here, Chaim sits down and offers Jocelyn heartwarming paternal solicitude (“God gave you such a beautiful gift. I just want you to use it.”). Standing in as Jocelyn’s paternal proxy in the wake of her mother’s death (Where’s her father amid this paternal subplot, by the way? Has there been a single mention of her dad in the series?), Chaim is a nice spin on the usually one-dimensional music manager.

It’s a hard sell, but Azaria gets it right, upending the conventional wickedness of his archetypal role. He does not even come off as sly or obsequious in these scenes. He knows money is part of the game. More than anyone, he is aware of the exorbitant price tag of the photo shoot and the music video and is rightfully concerned about blowing such massive sums of money. He knows digestible hit singles and touring are essential to keep the mortgage on Jocelyn’s mega-mansion paid. But he never loses sight of the brittle humanity of Jocelyn.

And to believe Jocelyn is a victim of industry pressures would be simply ignorant. As precocious and naïve as she seems to be, she could be living in a trailer park if she didn’t want to deal with the constant pressure. Very subtly, Sam Levinson highlights Jocelyn’s superfluously lavish lifestyle. She barely touches the gourmet meal prepared by her personal chef. As she walks around her palatial mansion, maids are busy cleaning vases in the background. She swims in a gorgeous indoor pool. She exercises on her lawn with fancy equipment and a private trainer. And her personal assistant is perpetually on-the-clock, opening her floor-to-ceiling drapes each morning.

Without any doubt, Jocelyn is actively reaping the many benefits from her capitalistic arrangements. She is thus complicit with the system. To a large degree, she subjects herself to the commercialistic demands of her record label execs and PR team by living in such opulence. As a result, Chaim is filling a role that is both necessary and largely motivated by Jocelyn’s indulgence. This is more common than our music biopics like to think, and the endless pillory piled onto the entrepreneurial side of this contractual arrangement feels overblown at times. For every conniving Nikki or manipulative Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), there’s a Chaim-like figure who can juggle empathy and enterprise.

To show just how harrowing and brutal the demands of the music industry can be, Levinson and his team dedicate the entire middle section of “Doubly Fantasy” to depicting a music video from hell. The chic and sleazy strip club set for “World Class Sinner” is the first ominous sign of emergent tensions. From the second Jocelyn walks into the backlot hanger, she is not happy: “This is not what I imagined. It feels like it’s too ironic in a way the fans won’t understand.”

This line is the first of many self-reflexive double entendres to arise as Levinson cheekily uses the music video to comment on the behind-the-scenes turmoil and pulpy qualities of The Idol itself. It’s an understatement to say The Idol’s production history has not been a happy-go-lucky affair. As already widely cataloged, Amy Seimetz (writer/director of She Dies Tomorrow, Sun Don’t Shine) was initially behind the project before being fired and replaced by Levinson. Given the dearth of female directors in the industry, this only exacerbated the Internet’s hatred of Levinson.

Whether Levinson instigated the firing or not (he didn’t), one could argue that he crossed an unspoken picket line. There’s been a call for more female-driven stories written and envisioned by women. There’s also been a growing resentment of Levinson’s depictions of women. Put these two things together and you have cultural dynamite; but it’s important to note that the specifics of a halted production are complex, convoluted, and largely inaccessible to the public.

Whatever side one takes, the public litigation of The Idol’s troubled production has overshadowed the series itself. Much of the messy breakup was prominently chronicled in a Rolling Stone piece, bearing the not-so-subtle title, “How HBO’s Next Euphoria Became Twisted ‘Torture Porn’.” Dropping a month before the series premiere, the piece is rife with speculative insinuation masquerading as incriminating evidence. It amounts to a vague collection of unsourced complaints about the show’s psychosexually perverse subject matter.

At the very end, one unnamed crew member cryptically complains about Levinson’s ability to “walk away unscathed and everybody still wants to work with him… people ignore the red flags.” This same production source vows to never work with him again, “Knowing how he treats his crew.” These gripes are alarming, but the fact that zero red flags are spelled out in any detail makes the entire ordeal incredibly dubious.

That the worst offenses these salty and anonymous crew members could conjure up were a chaotic creative environment and a moral repudiation for the series’ hyper-sexualized content says a lot: the piece was likely nothing but embittered crew members airing out their personal grievances.

To be honest, the article even spells out why its vitriolic agenda should be taken with a grain of salt, citing a factious atmosphere:

“There were also divisions among Levinson’s inner circle, the few crew members that remained from Seimetz’s shoot, and higher-ups at HBO, two sources say. One production member described feeling like a child of divorce, trying to tiptoe around the opposing parties.”

Few cared to discuss the obvious fact that a production undergoing an ugly “divorce” might facilitate uncharitable on-set sentiments. If anything, given such a hostile environment, it is a testament to everyone involved that the slanderous accusations were so utterly inconsequential.

Very few people also cared to recirculate any of the ardent rebuttals from well-known on-set sources explicitly defending the production. These counterclaims came from prominent members of the cast. At Cannes, Hank Azaria went on the record, stating, “I’ve been on many, many a dysfunctional set. This was the exact opposite.”

In another interview with Yahoo Entertainment, Jane Adams called The Idol “one of the best creative experiences I have ever had.” She went so far as to confront the online hysteria around Lily-Rose Depp’s nudity head-on: “I don’t even believe that mindset is real. That whole mindset seems fake to me, this outrage and pearl clutching.”

Adams didn’t stop here, calling out what she believes to be a false trend of puritanical probity permeating online spaces:

“I don’t know what is going on in society today, but there are all these people pretending they don’t have a dark side. I find that more frightening than anything in The Idol.”

HBO itself commented on the reports of The Idol being plagued by rewrites, delays, and reshoots. The network took full responsibility for the regime change, specifying their own discontentment as the inciting reason:

“The initial approach on the show and production of the early episodes, unfortunately, did not meet HBO standards so we chose to make a change. Throughout the process, the creative team has been committed to creating a safe, collaborative, and mutually respectful working environment.”

Unsurprisingly, this too fell on deaf ears. The Rolling Stone article reaffirmed what Levinson’s haters wanted to hear and went viral, inciting their already pervasive resentment and rancor. Thus, before most even saw the show, gloating about its abysmal Rotten Tomatoes score became a virtue-signaling pastime on Twitter. One was a bastion for goodness for reveling in its demise and viewed as heretical for endorsing it in any manner.

This mirrors note-for-note the very volatility at the center of Jocelyn’s career predicaments and music video frictions. Already enshrouded in previous controversies and an augmenting reputation of being unreliable, Jocelyn is under a tight microscope whenever she steps outside her palatial mansion. Like Levinson, who’s at once one of HBO’s most-prized creators after the success of Euphoria and reviled by critics/Twitter cliques from countless corners of the Internet, Jocelyn is immensely powerful yet treading on precipitous grounds (having been hospitalized for a mental breakdown). And fittingly, all her tensions come to a breaking point on set.

Of course, many have been quick to point out that the closest pop cultural parallel for Jocelyn is Britney Spears, whose private life has taken a very public and notorious beating from the paparazzi over the past few decades. Jocelyn’s outfit and the strip club aesthetic for the “World Class Sinner” video is the icing on the cake for this comparison, offering allusions to Britney’s iconic red-lace outfits, her signature red hair extensions and dark lip-liner (so prevalent in the late ‘90s and early 2000s), and her stripper themed video for “Gimme More” (the leadoff single for her controversial comeback album Blackout).

The choreography of the video, which becomes a central focal point of poor execution during the shoot, is also highly emblematic of Spears’ heyday. In the HBO Featurette at the end of Episode 2, the choreographer openly admits intentionally tapping into ‘90s era pop, describing how Jocelyn “controls the dancers but then also lets herself be manipulated.” This callback to Spears and Aguilera-era choreography is obvious yet fascinating—reinforcing how every facet of pop culture, even dance, can subtly and stylistically reflect the zeitgeist and its current gender archetypes.

The music video also follows a similar setup as the extended soundstage scene in Damien Chazelle’s Babylon. In Babylon, we witness Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie) and her supporting film crew struggle to adapt to the new demands of making motion pictures with sound. That scene’s focus has a more macro commentary, illustrating the clumsy transition from silent films to talkies. In “Double Fantasy,” the difficulties Jocelyn faces accentuate the travails of pop stardom, the grueling duress of making a music video (or a film for that matter) in general, and the challenges between actors/musicians and directors/creators.

From her fussiness regarding the strip club production design to her fixation on getting the choreography just right, it becomes transparent that Jocelyn herself is quite a perfectionist. It is also clear that she knows what is at stake at this point in her career. Multiple times during the shoot, Jocelyn’s director is satisfied with a cut and Jocelyn balks, claiming it’s not up to par for her standards. When she’s told by her team that she’s “pushing it,” she digs in her heels and rhetorically rebuts, “Is it bad to push for something that matters?”

Jocelyn soon becomes hellbent on tweaking the set and reshooting the next day. She is even willing to cough up the 450k extra this decision will cost. Her team, however, fear the optics of any delay—perhaps signaling that Jocelyn’s perfectionism was more of a stalling tactic or psychological escape strategy than anything. As Chaim exhorts, Jocelyn needs to go “Show them you got this and you’re fully committed.” He clearly fears the media fallout of recurring cancellations tarnishing Jocelyn with a reputation of flimsiness.

This all, once again, ironically resembles the constant media reports of the toxic production environment, constant reshoots, and last-minute revisions supposedly plaguing The Idol. Whether it is pure happenstance/coincidence or not, the music video couldn’t be any more self-reflexive of the commentary surrounding the series. According to a recent Variety article, however, it may be Abel Tesfaye who better fits the role of Jocelyn here. For it was he who pushed to scrap the initial $54-75 million project, claiming the “series was leaning too much into a ‘female perspective’”. Though the exact numbers vary, the pilot was tossed and reimagined anew, just as Jocelyn wants for the music video.

On the music video set, Tesfaye’s character, Tedros, is fleshed out through idle talk as Levinson splices together a Greek choir of overlapping rumors and narrative-fueled gossip. In my recap for “Pop Tarts and Rat Tales,” I noted some Altman-esque filmmaking motifs. Here, I want to revise this comparison. While Levinson’s editing evokes a similar sort of symphonic musicality, his overlapping dialogue is quite different. Unlike Robert Altman films, where the chatter occurs simultaneously in a single atmospheric setting, Levinson lets the conversations bleed into one another as he cuts from conversation to conversation/scene to scene.

The net effect of this technique is a dizzying and muddling of the information. The multiple overlapping dialogues thus evoke a sense of danger and mystique within the murmuring tittle-tattle circulating behind the scenes, giving one a sense of looming danger. The cross-edits also create unease, as the whispered canards and speculations spin webs of hearsay. Thus, while we learn more about Tedros—apparently his full name is Tedros Tedros (which everyone is quick to make fun of), he “owes a lot of people a lot of money,” and he’s from Hawaii—everything remains a bit suspicious.

For one, Leia doesn’t buy much of this secondhand information. This provokes Chaim to pry into her firsthand knowledge of the shadowy figure by asking her about his appearance and possible ethnicity:

“He’s a person of color.”

“Okay. What kind of color.”

“His hair is straight and it’s long.”

“Are you saying he’s black? You can say he’s black!”

The back-and-forth here is hilarious—showing the novel complications of performing detective work in a woke world where discussing the most basic profile characteristics is filled with nonsensical traps and fears. Due to the explosive pitfalls of modern identity politics clashing with limited parlance, it’s hard out there for a sleuth.

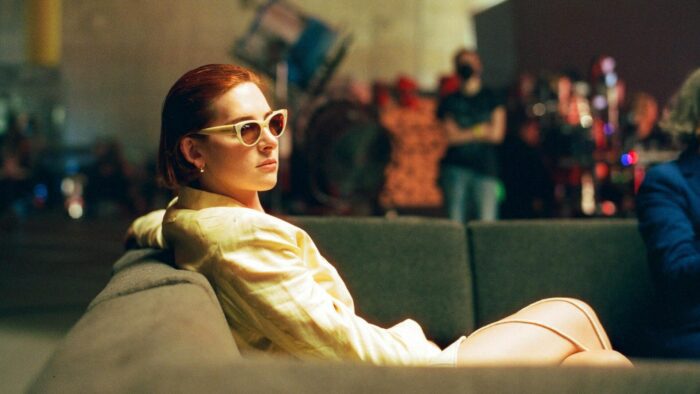

The music video also gives the Variety reporter, Talia (Hari Nef), a chance to redeem herself and appear slightly more rounded. She gets to show off her astuteness as a cultural critic, noting how Jocelyn’s “dancers are out-femming her,” and helping Xander contextualize Jocelyn’s comeback attempt in terms of the bigger picture: “She had a breakdown, her mother died, she was cheated on—she’s down right now. The context matters here.”

Jocelyn even seems ready to vulnerably open up to Talia a little bit. Self-aware and nervous about the optics of her visible on-set histrionics, Jocelyn confronts Talia in the backlot during a break and beseeches her to be sympathetic when writing her profile piece:

“I’m really sorry. Just the past year with losing my mom and everything. And being back here shooting the video is bringing up a lot of grief and I’m, like, more emotional than I thought I would be. I wish you’d take that into consideration in your article.”

Whether it is because she truly gets it or because she sees this as a first sign of intimacy, Talia genuinely reassures Jocelyn she’s not out to write a hit piece. Consoling Jocelyn by gently putting her hand on her shoulder, Talia attests that she will write her profile compassionately: “You’re only human.”

During this intermission, Jocelyn also receives a much-needed pep-talk from Destiny:

“I’m telling you right now those people in there are gauging whether you still got it. So, this is what you need to do: you gotta go in there and you got to give it your all. Because if you don’t, these people are going to f*ck up your career. But if you do, your fans are going to say, “Jocelyn is my mother-f***ing idol.”

Destiny’s speech is easily one of the more rousing moments in the episode—a real showstopper. But it’s also hard to discern whether Jocelyn’s interests are really in Destiny’s mind, or if she’s just exploiting encouragement to get her to push through the pain. This ambiguity is reiterated by Da’Vine Joy Randolph herself in the HBO Featurette, as she discusses her understanding of the character she’s playing: “Destiny may come off as manipulative, but I think her main goal is to make sure she’s safe.”

Ultimately, Da’Vine sees Destiny as a sincere person who has professional concerns but nonetheless cares for Jocelyn as a person. Like Chaim, she’s a positive paternal influence, and after their positive interaction, Jocelyn returns and nails her next cut, only to learn that the camera somehow fell out of focus. This is the emotional pinnacle of the episode—the point where Jocelyn reaches her Sisyphean peak and is immediately knocked back down.

To highlight the subsequent downward spiral, the cinematography shifts drastically. During Jocelyn’s successfully executed yet ultimately unusable cut, an infectious montage resonates with a sense of fluidity, coordination, and synthesis: Everything is vibing and on the same wavelength. Afterward, this feel-good montage gives way to long unforgiving takes fixating on Jocelyn’s bloody feet and the sharp cuts on her thigh. In the harsh light, Jocelyn’s cut marks now appear—exposed despite the hours of makeup she underwent (supposedly, she had an injury the night before, either from self-mutilation or some sort of masturbatory play involving a glass filled with ice between her legs).

Vulnerably on stage underneath the glaringly white light, the images of Jocelyn’s bloodied high heels and mutilated thighs recall the body horror of Aronofsky’s Black Swan, a dark ballet parable about mortal obsession. In no time, the glamour has devolved into grotesquery. Showing Jocelyn’s runny mascara, snotty nose, and saliva sticking to a Kleenex just moments after she was glamorized and commodified as a symbol of erotic beauty, Levinson’s sharp juxtaposition and starkly bipolar cinematography captures the way filmmaking twists reality—hiding or unveiling the blemishes/anguishes of the body.

I found the emphasis on Jocelyn spitting into a Kleenex to be particularly affecting. Mucus itself is a fitting emblem for the dual nature of the body: Equally erotic and disgusting (a sign of sexuality and a byproduct of crying and grief), it can be sexualized one second and monstrously repulsive the next.

In pain, overwhelmed, emotionally defeated, and just plain exhausted, Jocelyn soon slips into a psychotic episode, calling out for her mom in a moment that is one of the more visceral and harrowing moments of the young series. Chaim doesn’t help things by interrogating Jocelyn about her mental lapse. Luckily, Destiny has a defter touch and comforts Jocelyn with the kind of maternal support and graceful guidance she needs, motivating her without sounding bossy:

“It’s fresh and it’s early. I get it. I don’t care about these people. Because none of these people would be here or employed without you. F*ck that. You’re having a human moment. You can take a break. If you need 15, take 15.”

At the end of Destiny’s second pep talk, Jocelyn is visibly revitalized—firmly declaring she’s ready to power through. Unfortunately, Nikki comes in and sabotages the potential for a comeback, deflating Jocelyn by “crashing the party” (as she puts it) and calling a wrap on the set for the day. Some viewers viewed this as Nikki in “good-cop mode, urging her to take a break as she’s disintegrating.” I couldn’t disagree more.

Nikki moves in intentionally to manipulate the situation. She is clearly fed up with Jocelyn and eager to move on; having spotted Dyanne out-dancing everyone and listening to Dyanne sing, Nikki’s aim is to scrap the music video entirely and switch her allegiance. That’s why Nikki turns to Talia and tells her, “Your story is about to get a lot bigger.” By the end of the disastrous music video fiasco, Jocelyn is on the chopping block while Dyanne is being promoted to the next big thing.

Dyanne is also seen at Tedros’ (Abel Tesfaye) cult compound/nightclub, asking him if Jocelyn’s a better lay. We also hear Tedros enthusiastically celebrating the record label’s interest in Dyanne, even noting his excitement for getting a return on his investment. From this, we learn Dyanne has been planted all along. She’s very patently the bait, which makes sense given she’s the one who introduced Jocelyn to Tedros’ club in the premiere episode.

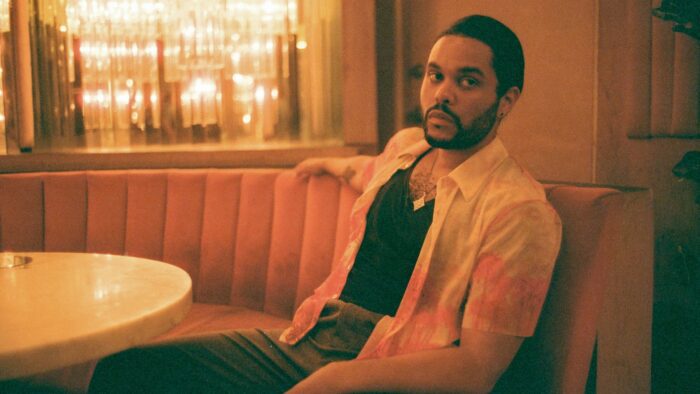

In fact, “Double Fantasy” answers many lingering questions surrounding Tedros after “Pop Tarts & Rat Tales.” Far from being Jocelyn’s muse or pawn, it becomes clear in the second episode that he’s a master manipulator helming a strange cult of sexualized musicians. He’s at once a psychopath out for a score and a slimy impresario. Here, the title—double fantasy—comes into play yet again, as Tedros is the mastermind behind two quixotic ambitions—using eroticism and artistry to procure entrepreneurial gains.

Somewhat problematically, the erotic thriller half of Episode 2 doesn’t match Jocelyn’s music video meltdown. The scenes involving Tedros feel increasingly incongruous with the sobering exploration of Jocelyn’s tumultuous return to the music industry. While the two storylines are clearly intertwined and coalescing, they currently feel jagged and in friction with one another, leaving one to worry about the overarching narrative and aesthetic intentions of the series. Is The Idol a wry, campy, erotic thriller? Is it a dark character study of a tortured artist beleaguered by a brutal industry? Or are both tones mutually desired? And if reconciling the two is the endgame, which it presumably seems to be, how does the series plan on marrying the two disparate modalities?

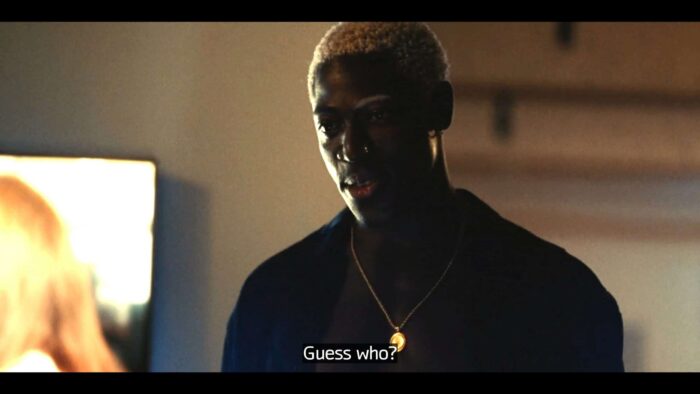

For now, many of the nuanced critiques have pinpointed this issue, citing how half of The Idol feels emotionally honest while the other half feels pulpy in contrast. Whatever the case, the Tedros subplot is spelled out in vivid fashion in “Double Fantasy,” beginning with an oddly jarring cut to Tedros zapping his underling Izaak (Moses Sumney), who is shown wearing a shock collar as he writhes and performs pelvic thrusts before a group of lounging young women. Between the buzzing of electrical shocks, Tedros commands Izaak to lower his stance and dig into his sexuality: “You’re not a human, Izaak. Don’t forget. You’re a f**ing star.”

If Nikki was a more conventional toxic managerial/pimp figure, Tedros is her sadomasochistic peer—puppeteering his minions with a mixture of suggestiveness and kink. To drive this ventriloquist metaphor home, Tedros’ nightclub features a weird dioramic display case filled with puppets on strings. He’s also clearly likened to a pimp, given that his compound is constantly populated by half-clad women counting money in the background and he’s seemingly always receiving a manicure whenever he picks up the phone. Trite signifiers aside, the juicy and labyrinthine plotting is fun in a pulpy sense.

Along with Dyanne, Tedros also plants Izaak and Chloe (played by Suzanna Son, the red-haired starlet-to-be in Sean Baker’s Red Rocket). Izaak’s role is not hard to infer—he’s tasked with wooing Leia. This is established early in the episode as after a brief telephone conversation where Jocelyn bemoans the negative reception their spunky S&M-themed remix received, the camera pans around to reveal Izaak simultaneously sweet-talking and courting Jocelyn’s standoffish assistant/confidante Leia.

The entire subterfuge sets further into motion in the final act as Tedros, Izaak, and Chloe show up at Jocelyn’s mansion for a night of debauchery. Chloe immediately undresses to skinny dip and Izaak leads Leia to her room, where things get heated quickly. During their foreplay, Izaak unloads some tongue-in-cheek exposition on how he ended up in Tedros’ sex-cult posse.

According to Izaak, Tedros randomly appeared at a church in Ladera where he used to sing and recruited him to his sect. The details aren’t spelled out, but Izaak ostensibly followed Tedros’ lead, ending up as a lab rat vocalist devoutly worshiping Tedros’ every command while donning shock collars. And when Leia retorts that she “would not expect [Tedros] to be into church,” Izaak’s response is quite layered and telling: “He’s very godly.”

Meanwhile, Chloe is more than a skimpily-attired sycophant. Donning star-shaped glasses that resemble the titular character of Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita, Chloe is very unabashed about her body. After skinny dipping, she runs around the mansion topless, even sitting down at the piano bench to play a classic piece. The resulting duality is quite provocative and daring—asking the viewer to conflate associations of an archetypal nymph with associations of a classically-trained prodigy. Chloe constitutes both sides of the spectrum—equally composed of Apollonian and Dionysian energies.

Eventually, Tedros gets Jocelyn alone, and he’s quick to seduce her—sexually and managerially. He starts off pleasantly enough, boosting her confidence by reminding her where she came from and how natural she’s become at navigating fame:

“You’re the American Dream. Rags to riches. Trailers to mansions. You’ve been a star your whole life. You’re going to forget how to do that now?”

The irony, of course, is that The Weeknd could be talking about himself, having grown up in poor neighborhoods around Toronto as the only son of Ethiopian immigrants. After all, the mansion The Idol is shot at and set in is his. (On a side note, I found it somewhat oddly serendipitous that a flurry of well-known media outlets decided to run articles just last week about Levinson buying an $8.5 million Beverly Hills Hacienda himself. I wonder what commentary they were trying to say about the series?)

Tedros also seems falsely overenthusiastic about spotting a Prince poster on Jocelyn’s wall: “Isn’t it crazy that the night we meet we talk about “When Doves Cry” and here you have his poster on your wall?” he rhetorically asks. Tesfaye oversells the coincidental nature of the poster and their bonding over Prince in a revealing way. Suddenly, it seems that even their tasteful synchronicity on the topic of Prince’s mastery was hypothetically premeditated. After all, having seeded Dyanne to recruit Jocelyn to his nightclub, it makes sense he did some reconnaissance homework in hopes of finding soft spots to connect and jibe with Jocelyn over.

Soon, the smooth small talk turns lascivious as Tedros and Jocelyn break into a softcore sex scene with scandalously gaudy, hardcore porn overtones. Much has been said about this segment, and it’s certainly a bizarre narrative pastiche of antipodal tonal elements. There’s Tedros’ stock-PornHub rhetoric (Delicious juicy ass. I’m going to f***ing devour you.”) that’s equally corny and cliché, and yet somehow noteworthy enough, despite its derivative vernacular and sensibility, to cause quite a disturbance online. There’s the voyeuristic presence of Chloe, watching the sexual rendezvous go down from a giallo-themed multi-mirrored closet, getting turned on, and putting her fingers in her mouth.

And then there’s the revving up of Tedros’ dirty talk that has caused quite a stir: “I’m going to suffocate you with my c*ck. Choke on it,” he says, slowly walking away from Jocelyn to command her platonically from afar, leaning on a chair. He then continues: “Ride it slowly. Put your finger down your throat. Open your legs. Stretch the tiny little p*ssy.” It’s critical to note that Tedros’ is clearly up to something. His commands are part of a bigger ploy, and he’s clearly on the prowl, trying to swoop in during a time when Jocelyn is searching for an authority figure—someone to replace her deceased momager figure.

Disregarding the narrative function, most of this discourse over the bossy NSFW sex talk has been either dubiously prudish, comically hyperbolic (here’s an excellent breakdown of how The Idol’s supposed raunchiness and shock value pale in comparison to countless HBO projects), obdurately offended, or predictably reactionary (I.E..:“[the] gross scene at the end of the second episode was a disappointing omen that the series is indeed setting sail for a season of male navel-gazing and boring sex disguised as subversion”).

To temper the pushback, Tesfaye has tried to defend his character’s portrayal by pointing out the fact that Tedros is meant to be over-the-top sleazy and over-his-head sketchy:

“The reality is, there’s nothing mysterious or hypnotizing about him. And we did that on purpose with his look, his outfits, his hair—the guy’s a douchebag. You can tell he cares so much about what he looks like, and he thinks he looks good. But then you see these weird moments of him alone—he rehearses, he’s calculated. And he needs to do that, or he has nothing, he’s pathetic.”

I personally think the screenwriting, albeit pulpy to a garish degree, works well regardless, and apologetically justifying the scene or character somewhat reduces its complexity. Remember that before things get steamy, Tedros places his hands over Jocelyn’s ears to “block out the noise,” a call back to his speech in the premiere. It’s clear that he wants to be the sole voice in Jocelyn’s head—the mastermind controlling her career (“I’d bet a billion dollars on this. If only the world could see what I can see now.”). As Jocelyn “turns into a living sex doll who hinges on his every word”, Tedros is not just some schlub loser. He’s confidently insecure, and successfully camouflaging the feeble parts of his ego by virtue of his predatorial performance.

My primary disappointment has less to do with Tedros’ tawdriness than his artistic fidelities. In “Pop Tarts and Rat Tales,” he seemed to genuinely care about pop music’s underrecognized potential for authenticity. In “Double Fantasy,” these impressions play second fiddle—artistry seems to be the last thing on his mind. The monetary potential of Jocelyn’s talent and inculcating submissiveness are his primary targets, which is why he’s so hellbent on trading Dyanne.

Thus, Tedros’ decision to remove himself physically and dictate sexual orders metaphorically reinforces his desire to shape Jocelyn as a manager/director. Sexual gratification is not even his main agenda; it is simply a conduit used to foster trust and dependency. Tedros has a purely psychosexual interest in Jocelyn, and this, we learn, is one of his pathological attributes: Eroticism is his managerial method of training and grooming underlings.

Sensing Jocelyn is aimless and empty inside, Tedros’ alpha certitude fills a void, as maladroit and sleazy as his methods may seem. Tedros’ kinky bedroom demands turn him into something Jocelyn’s current PR team and artistic collaborators can’t be—an overlord who seemingly cares about her deeply embedded hormonal sensibilities. Tethered to capitalistic and bureaucratic constraints, Jocelyn’s current team can’t truly possess her mind and body because they’re always stuck at a safe, ascetic distance. And the artificial, unfeeling nature of their mentorship leaves her craving something more intimate, personal, arousing, invested, and libidinally alive.

Tedros, meanwhile, sees Jocelyn’s untapped potential, recognizes her powerful voice, and is trying to swoop in, “reach down,” and “pull it out.” He’s a thief trying to pull a heist, using sex as his instrument to get past the firewalls of Jocelyn’s fortified psyche. As a result, my sole gripe with the salacious final sequence is that Tedros ultimately receives fellatio. I found their relationship more credible and symbolic before we see direct, sensual contact. For me, Tedros getting off was an odd call on a storytelling level, diluting the metaphysical/psychological power he had previously wielded over Jocelyn by getting her off from afar. Keeping the erotic entanglement solely verbal would have only heightened the satirical heft—exaggerating his imposing and deified stature.

Nevertheless, Tedros’ scam pays off. Exploiting Jocelyn’s postcoital openness, he subtly comments how it’d be “easier if I moved in.” Jocelyn complies, thrilled at her newfangled pimp/dominatrix living with her; and then suddenly, like a Siren song, the sound of Chloe singing downstairs echoes through the mansion. The lyrics to her plaintive tune are telling: “That’s my family. We don’t like each other very much but I’m okay with that.” Slowly, Izaak joins in, harmonizing, and then Jocelyn appears, gradually finding herself washed up by the melody—seduced by a song clearly implanted to lure her out of her shell.

As everyone sings, Leia’s horrified, pale, and ghostly face says it all. Living up to her role as the cautious and guarded assistant/confidante, Leia knows Jocelyn has been tempted and duped by a conman with a clandestine game-plan. On this somewhat platitudinous note, the episode ends—leaving one fearful that the show’s vision is slowly becoming compromised. Whether this is due to fractious rewrites, Tesfaye’s unfounded yet purported megalomaniacal interventions, the rush to produce content, or simply missteps in artistic integrity, there are nascent signs of The Idol falling into conventional tropes of serial TV.

Time will what becomes of these developments, but as it stands The Idol is on the verge of careening towards a hackneyed dead-end, becoming a stuffy fable of manipulation as opposed to a twisted tale of the codependent pursuit of erotic and artistic authenticity. It’s still thoroughly entertaining, despite the rush online to state otherwise, but the next few episodes will be quite decisive on what direction this series is going. It might also be critical for the posterity of the show, as rumors of its cancellation have already been published and denied.