If you’re expecting an unbiased critique of the Virtual Boy then I’m afraid you’ve come to the wrong place. The console’s failings are well documented, and its reputation is already one of infamy. To me however, the Virtual Boy was always something of a ‘unicorn’ system—something highly desirable, but always just out of my reach. Well, that was until recently. On the 25th anniversary of its North American release, I want to share my personal story with Nintendo’s most notorious system.

“It will transport game players into a ‘virtual utopia’ with sights and sounds unlike anything they’ve ever experienced” – Hiroshi Yamauchi

Perspective is a funny thing and my view of the Virtual Boy is in large part determined by my location. I live in Europe—Britain to be precise. In the 1990s, video-games would trickle out of Japan, land in America, and then, several months later, finally arrive in PAL regions. In magazines, we would gaze longingly at the wonderous new consoles and games coming out overseas—eagerly awaiting the day they would arrive in our local highstreets.

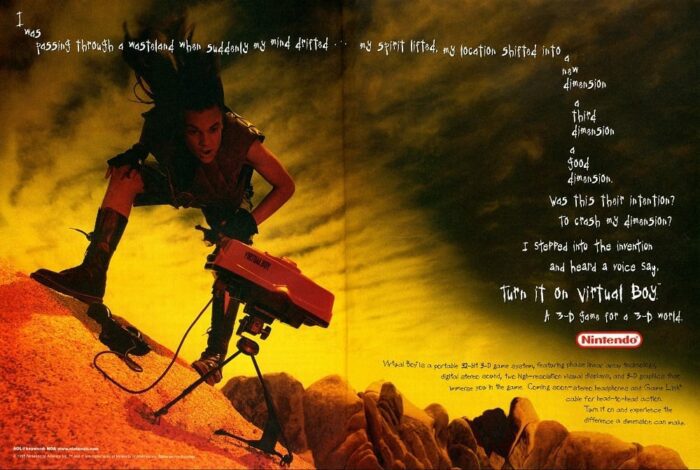

I remember poring over news of the upcoming Virtual Boy as a 10-year-old. Even then, early reports were peppered with concerns, ranging from the high price, to a lack of compelling software. Even Nintendo’s official UK magazine (Nintendo Magazine System) often covered the machine with a cynical tone. None of that mattered to me however—I’d been enamoured with the system since I first laid eyes on it.

A Window to a Virtual Dimension

How many kids who grew up in the ’90s remember being told to “sit away from that TV or your eyes will go square!”? Like a moth to the flame we were compelled to get closer to the glow of our small CRT televisions—we were entranced. I remember taking that compulsion even further, erecting a makeshift cockpit to play Starwing on the Super Nintendo from a dining chair and a bedsheet.

Starwing (or Starfox as most of the world will know it) was a particular favourite of mine. I was infatuated with the 3D polygonal graphics. They gave the game a depth which made it feel almost tangible—like I was peering through a window into another dimension. The ‘cockpit’ I’d built helped to block out the real world which would otherwise break the illusion.

The Virtual Boy seemed purposefully designed to create that same sense of immersion. Of course, it fell short of true Virtual Reality, with most games being traditional third-person affairs. But it offered a greater level of escapism than my DIY solution had (minus the blatant fire-hazard). Plus, it was actually 3D, not just the illusion of 3D like Starwing had been. Yes, it was monochrome, but I’d grown up with the Game Boy—that didn’t bother me—besides, there was something oddly futuristic about the red-on-black LED screen. I couldn’t wait to get my hands on one. Little did I know that it would take 25 years for that to become a reality.

Heartache and Headaches

My Dad used to go on infrequent business trips to Japan—one such trip was in the summer of 1996. The machine had been out for a year at that point, but there was no UK release date in sight. This was an opportunity to get my hands on something that seemed a world away. I pleaded with him (in the way only a slightly spoiled 11-year-old can) to bring me back a Virtual Boy. My Dad said he’d try to find one (although he didn’t have any idea what one was). That week was one of the longest of my life. I remember that feeling of impatient longing like it was yesterday—I also remember what he said to me when he finally came home.

“That Virtual Boy, I tried to get you one but I was advised not to—apparently people are getting bad headaches from them.”

I was crushed (again, in the way that only a slightly spoiled 11-year-old can be). I’d heard rumours of headaches and eyestrain but hearing my Dad confirm it from the source was utterly disheartening. It was at that point that I realised that the Virtual Boy was never going to make it to Europe. Coverage of the system had already gone from sparse to non-existent. Nintendo, and the world, had moved on. The Virtual Boy that I’d dreamed of owning had turned out to be just that—a dream. Whereas most dreams are quickly forgotten however, this was one that I could never shake.

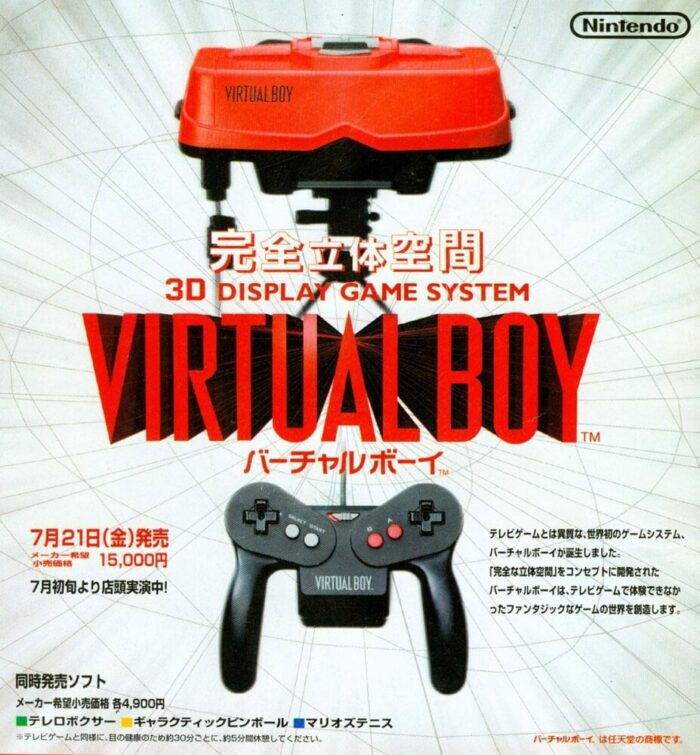

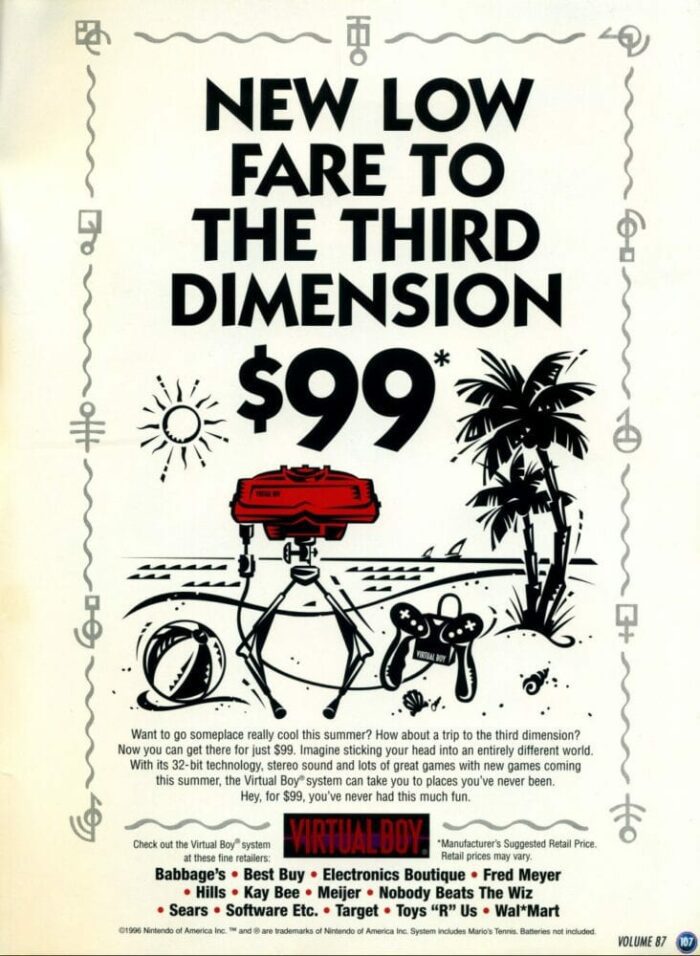

Looking back now, it’s easy to see why the gaming press and public were so quick to gloss over the system. In the years of 1995 and 1996 the world of gaming took a great technological leap. The Sony Playstation, the Sega Saturn, and the Nintendo 64 all released within those two years. It’s hard to imagine a world in which the Virtual Boy could sell well amongst such competition. To add insult to injury, the Game Boy Pocket would also release, making for a cheaper, more practical, handheld option. I didn’t appreciate any of that at the time—I was gutted. Nevertheless, I quickly became swept up in the exciting new consoles and the Virtual Boy faded into a distant memory.

Close Encounters of the Virtual Kind

In later years, the Virtual Boy became something of a bucket list wish for me—along with wanting to visit Japan. It was the sort of thing I’d reply to the question “what would you do if you won the lottery?”. I’m still yet to win the lottery, but in 2015 I did at least achieve my dream of going to Japan. It was my honeymoon, and despite it being wholly inappropriate for the occasion, I went there fully intending to ‘kill two birds with one stone’.

My wife and I were having the trip of a lifetime. We’d travelled from Tokyo, to Kyoto, to rural villages and hot springs before spending our last few days back in Tokyo. It was here that I first saw a Virtual Boy in the flesh (well, in the plastic). It was in the famous retro-gaming emporium, Super Potato in Akihabara—a treasure trove of Japanese video-game history. Taking pride of place in the shop, was a Virtual Boy demo unit. I was finally about to experience something I’d obsessed over as a child. As I walked over to it, I noticed a piece of note-paper with a scribble of Japanese on it. I turned to the shop clerk and pointed to it inquisitively. His response was to cross his arms into an ‘X’ shape. A simple but effective translation.

Elsewhere in Super Potato, on a shelf, sat a seemingly brand-new Virtual Boy. The box was enormous—much bigger than I’d expected—the price was too. The trip (along with the wedding preceding it) had been the most expensive thing I’d ever done. Between train fares, accommodation, incredible food, and bags of souvenirs we were all but spent. The Virtual Boy would have swallowed the remainder of our spending money entirely, as well as providing a headache for the return journey (and not the kind of headache I was looking for). As much as it pained me, I decided against sabotaging the remainder of my honeymoon and put it back on the shelf. Once again, the system had eluded me.

One Man’s Trash is Another Man’s Treasure

It would remain that way until just a few weeks ago. I’d had a lucky find, accidentally acquiring a factory sealed, and highly desirable N64 game for a bargain price. Straight away I knew that this was my ticket to a Virtual Boy. I didn’t even wait to sell the game—I’d waited long enough—I didn’t need the money so much as I needed the justification. I immediately started scouring eBay and Facebook groups for units for sale. Prices were higher than ever, but I didn’t care. Within a week, I had a parcel arrive at my house.

The seller had been UK based. He’d bought the system on a holiday in the United States as a child along with a couple of games. I don’t know what it had meant to him, and I doubt he knew what it meant to me. Maybe he’d grown bored of it as a kid and it’d been residing in his parent’s loft until he’d decided to stick it on eBay. Who knows? All I knew was that inside this box was, at long last, my Virtual Boy.

I relished unpacking it. Taking each piece and turning it over in my hands, taking in every little detail. First the stand, then the controller, then the unit itself. You couldn’t wipe the smile from my face. I assembled it, slid in Mario’s Tennis, pressed my face into the eye mask and turned it on. To my delight, it blinked into life immediately. I must have spent at least a couple of minutes just staring at the warning message that pops up initially. I couldn’t believe how bright and sharp the red pixels looked on the pitch-black background.

Upon starting the game, Mario’s Tennis opens with a cutscene of the man himself serving the ball into the viewer before the title screen zooms into view. The 3D effect looked pronounced and multi-layered. The eye-mask completely blocked out the outside world. The screen seemed to sit in the distance, I felt like I was sitting in the back row of an empty cinema. Somehow, it was everything I’d dreamed it would be.

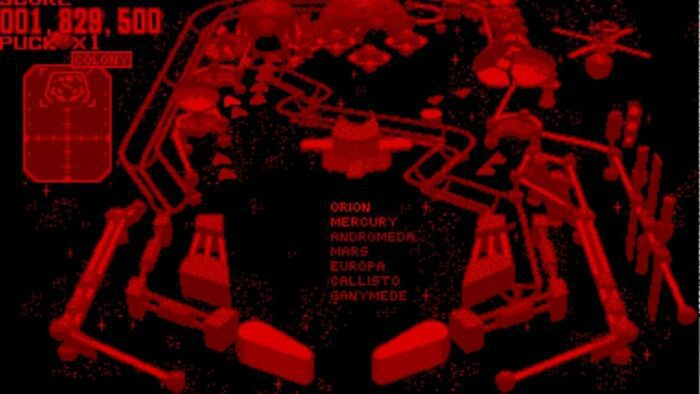

The other game I’d received with the system was Galactic Pinball. To my surprise, I found it even more compelling, and better suited to the Virtual Boy’s unique selling points. The game is dripping with an overt retro sci-fi vibe. The music is a blend of triumphant melodies and Metroid-esque creepiness. Unsettling warning sirens will trigger at certain points to match the action over the stereo speakers. There are a selection of galactic-themed, bottomless tables to play on—each suspended over a slowly scrolling background of star clusters and asteroids. The Virtual Boy’s, isolated, 3D display, and red-on-black visuals seemed to perfectly match Galactic Pinball’s lonely sci-fi atmosphere. It’s a fun game and one that would be a lesser experience on a traditional console.

Virtual Myths and Virtual Realities

I’ve now had the system for several weeks and I’ve played it near enough every day. My collection of games has expanded to six titles (over a quarter of the entire Virtual Boy library). I’ve yet to experience any headaches or any other negative effects that reportedly plagued the system. Having spoken to other owners online, the consensus is that it is something that’s been overblown over the years. Some even describe it as a myth—a result of failing to properly calibrate the system to the user’s eyesight before use. Personally, I’ve found the 3D effect to be comparable to a 3DS and, because the picture is static, clear, and sharp, much more comfortable to look at than some modern VR.

Elsewhere, the console’s failings are far more apparent. As hinted at, the library of released games is tiny, weighing in at just 22 titles. A fair few of those are notoriously terrible, or out of the price range of most collectors. Strangely, some quality titles are remarkably cheap—I was able to pick up previously unsold, Japanese copies of Golf, Red Alarm, and Vertical Force for less than their original RRP. Other must have titles are depressingly expensive with Wario Land, and Atlus’ Jack Bros demanding three figure prices.

More depressing is the list of titles that were cancelled entirely due to the early retirement of the console. Most of them were unbeknownst to me. Seeing exciting titles on the list from series such as F-Zero, Donkey Kong Country, Bomberman, and Mario Land was heart-breaking. To know that we’ll never see how these games would have turned out makes me feel as frustrated as I did when the console seemed a world away.

Reddy or Not…

Even some of the titles that did release feel noticeably hollow. Mario’s Tennis for instance, only contains two modes—singles or doubles. You can play in single matches or in a tournament setting with three stages of difficulty. There are seven playable characters, which makes for an odd number of opponents in tournaments. It means that one character is left to automatically advance to the second round. Similarly, in doubles, one character has to appear twice to make up the numbers. Winning the tournament will see you presented with the underwhelming text “Congratulation!” without so much as a still image to accompany it.

I was also surprised to learn that the game (and in fact the console) doesn’t support link-cable multiplayer. Inspection of the game’s source code has since found that it was a feature that was originally included but subsequently disabled before release. It’s solid evidence that supports the stories of the Virtual Boy having been rushed to market.

Gunpei Yokoi (designer of the world-beating Game Boy) had overseen development. The innovative 3D display technology had been provided by US based Reflection Technology Inc. Originally intended to include goggles, head-tracking, and a full colour display, the console’s features had been significantly downscaled to remain affordable. Gunpei Yokoi was reportedly reluctant to release the system in its final state, wanting more time for development. Due to the company’s resources being increasingly focused onto the upcoming N64, Nintendo were unwilling to delay any longer and insisted that the Virtual Boy be released regardless. The rest, as they say, is history.

To a discerning adult, or industry critic in 1995, the flaws of the ill-fated Virtual Boy were obvious. To a 10-year-old boy, reading about the system in magazines half the world away, it seemed wonderous. The 35-year-old author of this article thinks that the Virtual Boy is continually heart-breaking, and endlessly alluring.

Happy 25th Anniversary.