I do not doubt that it would be easier for fate to take away your suffering than it would for me. But you will see for yourself that much has been gained if we succeed in turning your hysterical misery into common unhappiness.

– Sigmund Freud, Studies on Hysteria (1895)

As a therapist, Laurie Garvey devoted her life to helping others. Psychology is imperfect, of course — it’s difficult business, trying to figure out how to help those who suffer variously with being in the world — but this was her calling. There is every indication she was good at it.

She had a son at a young age by a man who was by all accounts a jerk. Later she married Kevin Garvey, a man who took that son on as his own and was seemingly a good husband (for the most part). Of course there is the question of how good of a partner any of us can be when we’re all tied up in our own neuroses, dealing with the world, but it seems like Kevin did OK. Together they had a daughter they named Jill, and, well, things weren’t perfect, but they never are. Yet the Garveys were, at least, a family.

Laurie was pregnant when the Departure happened. She hadn’t told Kevin about it. It wasn’t planned, and from a reflective point of view, at least, another child was not something she wanted. She probably knew at some intuitive level that Kevin didn’t either. It’s not clear whether she would have had an abortion if things had gone differently. This doesn’t seem to be on her mind when we see her getting an ultrasound — a scene that might indicate that she was going to keep it — but these things are complicated and murky. It’s not a decision anyone takes lightly.

In this case, it was a decision that Laurie didn’t get to make. The fetus disappeared on October 14th, at the very time that she was having that ultrasound. And she didn’t tell Kevin about this, either. How could she? Think, for a moment, about what that would be like. Whether she wanted the baby or not becomes irrelevant. There is a particular sort of pain about miscarriage that we don’t talk about a lot. It’s an intimate sorrow, and one that can also be felt by women who have had an abortion (a miscarriage being what is medically known as a “spontaneous” version of the same). It’s all about context.

Politically, people have railed against late-term abortion for some time, in a way that makes clear that they have absolutely no idea what they are talking about. These occur due to the discovery of severe defects, threats to the life of the mother, etc. They are sad stories of wanted pregnancies gone wrong. There’s a decent chance you know a woman who has had an abortion, and there is a whole spectrum when it comes to how she might feel about this. But if you know a woman who had one late-term, she probably told everyone it was a miscarriage, and will only confide in you about it late one night, crying on your shoulder after you’ve both had several glasses of wine.

And there is good reason for all of that, because late-term abortion is essentially a miscarriage; it is not a willful termination of a pregnancy, but something else. The point is that Laurie’s sorrow in relation to her departed fetus has nothing to do with whether she wanted to have another child. It’s that — like the miscarriage, or the pregnancy that has to be terminated because something has gone horribly wrong — this happened without her consent

She lives with this, telling, it would seem, no one. She goes about her practice for a while, until Sam’s mother tells her about her own struggles to get pregnant. They went to fertility doctors and did everything they could but none of it worked. Until, one day, miraculously as it were, there was baby Sam. On October 14th she was arguing on the phone with someone — who cares who it was, or what it was about — while Sam fussed in the backseat of her car. She knew he’d settle down once they were moving, that the movement of the vehicle would calm him. But then he stopped, and when she looked back he was just… gone.

She went back every day, in case he returned to that same spot. And if he was going to return, wouldn’t it make sense that it would happen that way? He’d need help, of course, because he’s just a baby. So Sam’s mother went back, just in case, just hoping that her baby boy would come back to her. Is this crazy? Should she stop?

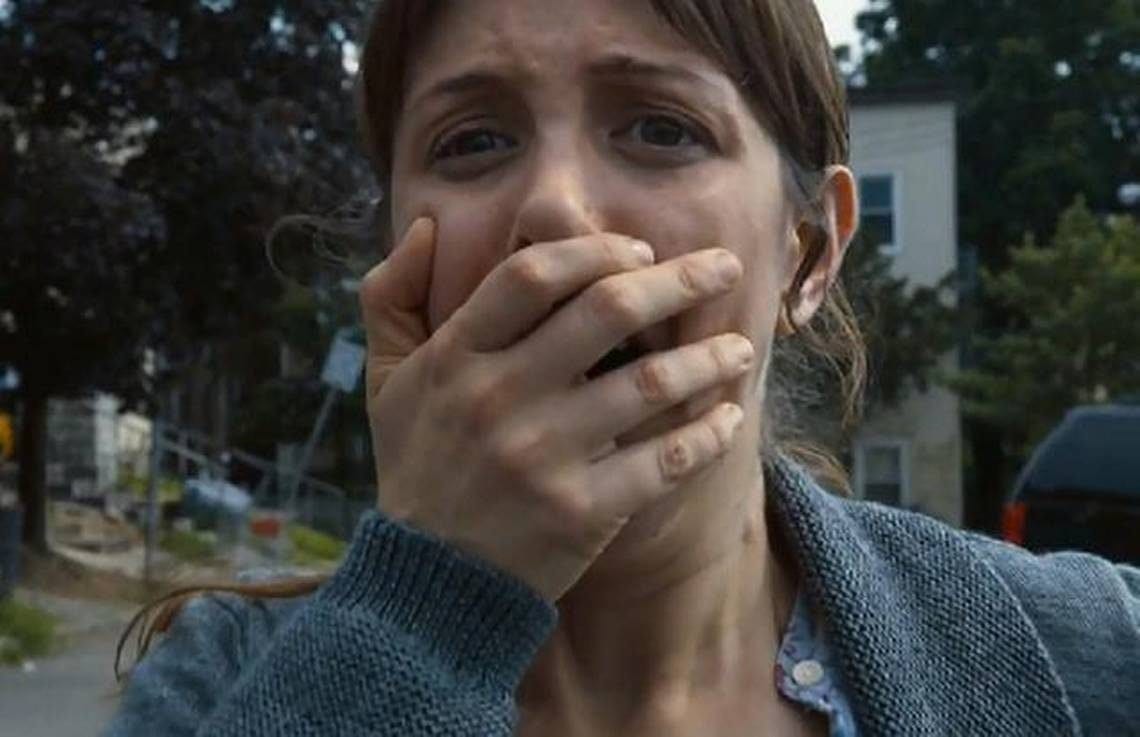

This is what she asks Laurie, her therapist, but the latter doesn’t know the answer. The Departure threw the world out of joint. With no explanation for how or why, baby Sam disappeared. How could anyone decide whether it is irrational to hope that he might reappear? And if you’ve devoted your life to helping the mentally ill, what does it do to you to face a moment where you are no longer sure what is, and what isn’t, madness?

We need a line between sanity and insanity, between the rational and the irrational. It allows us to determine what makes sense and what doesn’t, and what could be true and what couldn’t. Defining reality is not just about delimiting what exists but about determining the limits of what is possible. And if you want to help people who are struggling with that, well, you had better have a pretty firm grip on the distinction yourself.

This is why Laurie Garvey is led toward suicide after her exchange with Sam’s mother. It is not so much a personal despair as an interpersonal one. The “talking cure,” and even more broadly rational discourse, relies on a certain kind of faith in reason itself. That is, it relies on the faith that one can, through the power of something like reason, bring people to grips with reality or have an effect on how they view the world. And if trying to do that is your vocation, as it is for Laurie, then the breakdown of it represents a true existential crisis.

This is something we should all be able to relate to, as we are caught in these echo chambers created by modern technology. The news is supposed to tell us about reality but it’s increasingly hard to take anything as “objective.” Our social media feeds tend to reinforce the views of the world we already have, and the same goes with the things we watch. We’ve ended up with competing views not just when it comes to what we value, but when it comes to reality itself. Try talking to someone across the political divide in this day and age and you’ll find that you not only disagree; you disagree about the terms of the disagreement. This is not to say they are crazy, but simply to point to a certain despair of reason. If we lose faith that talking to each other might be helpful, then what?

Suicide might seem like an answer, but it is a hollow one. There is something self-centered about it. The lack of meaning in life does not justify an ending of life; this thought would be to raise that nothing to the level of a grand overarching something. But the nothing is just that — nothing. It is a mistake to reify it. Laurie realizes this, and that it is perhaps important that life is absurd. So, she vomits up her pills and joins the Guilty Remnant. They get that the world has ended, that nothing makes sense anymore. They provide a purpose without meaning.

The question is not so much why Laurie decided to join the GR as it is why she decided to leave it. The most direct answer points to her daughter, Jill. She gave Laurie a Zippo engraved with a message that implored her not to forget her, which Laurie chucked down the sewer but came back to retrieve later. And, shortly before they were burned down, Jill came to the GR houses to be with her mom, one supposes.

It is during that fire — after Kevin arrives to save all of the members of the GR he can — that Laurie breaks her silence. And, in a heart-wrenching moment, she screams to her (ex)husband the name of their daughter: “Jill!”‘

It seems clear that this was the turning point. It may seem cynical to even ask why, but given the GR’s stance that there “is no family” at least a word seems to be in order. That is, Laurie’s outcry seems to be an explicit rejection of that aspect of GR doctrine, and thus of the doctrine as a whole. Her daughter is at stake; enough with the “world is over” bullshit.

It is the love of family — and even more broadly, the love of others — that brings Laurie back from the GR fold. Maybe there is no meaning, in some grand overarching sense. Maybe there is no reason, or space of reasons we can expect everyone to be able to inhabit such that we can figure things out and get along, or at least get by. Maybe there is none of that, but there is love: the love of a parent for a child, or a child for a parent; the love of siblings; the love of friends, or romantic partners. There is love, and it is not rational.

Love is patient. Love is kind. It does not envy. It does not boast. It is not proud. Love pushes us beyond ourselves and our worldviews. We can love those with whom we vehemently disagree. This isn’t empathy so much as it is something else. To love is to take someone with all of their flaws and to care about them anyway. There is something absolute about it, but also something wildly irrational. You might support all of the heinous stuff in the world, but I still love you, and I can’t help it.

So when Jesus says to love your neighbor, he is not pulling some kind of Mister Rogers thing. Your neighbor is a jerk. Your neighbor plays their music too loud, or bangs their bed frame against your wall while having sex. Your neighbor rants about a green banana bicycle, or beats his wife. Your neighbor is not your friend; on the contrary — that’s the point.

Though it may have been her love for her daughter that pulled Laurie back into the world, we quickly see her taking up once again a love for others in a broader sense. She strikes out to help others get away from the GR, for example. It is no longer through the lens of modern psychology that she focuses her attempt to help, but from a broader existential point of view informed by her own time with the Guilty Remnant. Her position becomes less informed by reason, or attempting to help people on the basis of reason, and more one informed by love in the sense of agape.

This is not to suggest that Laurie becomes a Christian, if that means anything having to do with belief in God, but merely to point to an existential turn on her part. In fact, far from her previous commitment as a psychologist to steer people away from their delusions, we find Laurie fully willing to employ delusion for therapeutic purposes. If a woman she tried to help get away from the GR ended up killing herself and her family in a car wreck because she wasn’t offering anything to replace the void left by turning away from what the GR offered, then Laurie wants to offer something. Thus, she encourages Tommy to take on the role of Holy Wayne for them, even though both of them know it’s malarkey.

Equally, when she joins forces with John Murphy to mimic the business of the maybe-psychic Isaac, it makes less sense to think that she does this for money and more to think that she conceives of it as a matter of helping people. She tells Nora that they don’t do Departures because, unlike those who have lost loved ones to death, those who have lost them to the Departure don’t want closure.

They’re manipulating people — John pretends to be psychic while Laurie uses some impressive internet skills to look things up and feed them into his earpiece — but money isn’t Laurie’s goal. When John shreds a payment, she doesn’t bat an eye. She mentions it to him later, but even then it isn’t about the cash but about what’s going on with John.

When she joins Matt, John, and Michael on their trip to Australia, it seems clear that this is also about trying to help Kevin. She doesn’t buy into all this stuff about him being metaphysically special; she just knows that he is in trouble, after he has called her to tell her he’s delusionally thought a young woman to be Evie Murphy.

Yet, when it comes down to it, she doesn’t try to talk Kevin out of going through with the plan his father and others have set out for him, even if she does poison the others so that she and Kevin can have a talk alone. You want to kill yourself so that you can talk with people beyond the veil, and you’re confident that at least maybe you could come back? OK, Kevin. Laurie may think it’s crazy, but she can’t deny that she now lives in a world where crazier things have happened, or that those she cares for have testified that this very thing has happened before.

Their conversation is in every way an exemplar of that between a divorced couple who still love each other. They are brutally honest, but the brutality is gone. These things, which would have been brutal or hard to deal with when they were together, can now just be revealed without drama or conflict. “Why didn’t you tell me [you were pregnant and lost the baby to the Departure]?” Kevin asks. “Because I didn’t want to… and then I didn’t have to,” Laurie replies.

There’s no judgment here; this is catharsis. Maybe you need to have been in a relationship like this to connect to it: one that failed for no good reason, other than the world getting in the way; one that ended without acrimony, but ended nonetheless; one where you have never stopped loving the other person, even though that love has completely changed in form; one where, from a certain point of view, the fact that it ended makes no sense, or is a bit absurd. I don’t know. I don’t know if you’ve had that or not, or if you can connect to this scene even though you haven’t, but if you have you know that it can open a weird kind of space where there is just no need to dissemble with one another about anything anymore. You can admit that you killed your kid’s hamster, or lied about a business trip to spend some time at the spa, and just laugh about these things together. In a weird way, this is love, even more than those romantic versions we tend to aspire to.

And so Laurie doesn’t try to stop Kevin at all. She just wants to say goodbye. Maybe that’s a goodbye because of what Kevin is about to do and she doesn’t believe he’ll survive it. Maybe it’s because she intends to follow the plan Nora set out to her, and commit suicide when she goes scuba diving, and is only kept from doing that by a fortuitous call from Jill. Or maybe it is just because, one way or another, she knows this is the end of their relationship, whether they happen to see each other again or not.

I prefer that last interpretation, personally. I don’t think she intended to kill herself on that scuba diving trip — as much as the show plays with the ambiguity and it’s really not clear why she went scuba diving otherwise — because it doesn’t make much sense to me that she would do it at that point. She might think that Kevin is about to kill himself, but between that and the third option I laid out, I think it is almost a difference without a distinction. Whether he dies or not, she knows this is the end of their story. If there happens to be anything else, it will be an epilogue.

She kept talking to Nora, however, and at least one part of her psychologist ethos remained: doctor/patient confidentiality. In a scene that strongly resembles the one from Breaking Bad where Saul Goodman asks Walter White and Jesse Pinkman to “put a dollar in [his] pocket” to secure attorney/client privilege, Laurie asks Nora for a dollar to do more or less the same.

The law isn’t what matters here, though. What matters is that Laurie feels ethically bound to keep Nora’s confidence. She doesn’t tell Kevin, and it would seem that she doesn’t even tell Matt that Nora was been in contact with her. Because what could justify her in doing so?

If you’ve given up on universal reason and abjured the position that finds a purpose in doing the same, what are you left with if not love? Patient, kind, without envy or pride, you love people. And what right do you have to tell their secrets?