One of the most striking things about Lost has always been the sheer number of character names that seem to allude to real world people throughout history. There are so many, in fact, that I’m prone to wonder whether perhaps some of them are incidental. I don’t quite think there are, but I’m also not entirely sure what to do with someone like Radzinsky. Is this a reference to the author? Maybe, but it at least doesn’t lead me personally down an intriguing line of thought. (If it does for you, please comment and share!)

Other name references in Lost strike me as almost too straightforward, though they may well inspire interesting lines of thought. Daniel Faraday is a scientist interested in electromagnetism and his name is clearly a reference to Michael Faraday, which is great and could feed right into your favorite theory about how Lost characters are actually related to these historical figures, but in terms of thematic significance, I’m personally not sure how to take it much further.

Equally, Richard Alpert was the name of a real person (alive when Lost was made, no less!) but I’m not inspired to say much more than to make the note that perhaps there is a connection to the teachings of Ram Dass that informs his character. Or maybe we’d get a little further considering how Ram Dass described his own movement from atheism to belief.

Rousseau is clearly a reference to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and while there may be interesting parallels to explore in that regard, I expect that you hardly need me to tell you that Lost plays with ideas pertaining to notions of the State of Nature and Social Contract.

Regardless, herein you will find a list of my five favorite name references in Lost. These are the ones that have inspired the most thinking in me, or where the allusion fed the most into my appreciation of the show. My background in philosophy will be apparent.

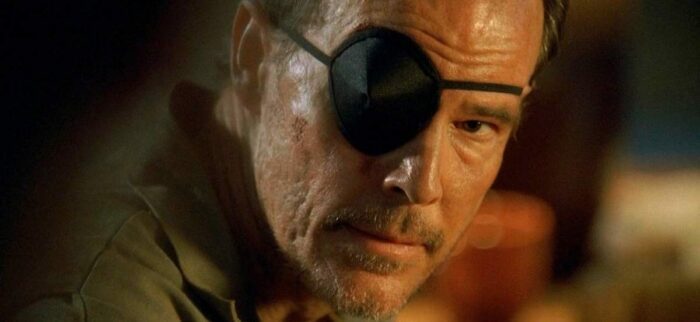

Mikhail Bakunin

Let’s start with Mikhail Bakunin because his whole name is actually the same as that of the 19th century thinker who is central to the debates between Marxists and anarchists that continue in certain quarters to this day.

Bakunin promoted anarchism, but from a distinctly leftist point or view. His worries about Marx (and the idea of Communism) centered around the latter’s idea of a dictatorship of the proletariat. Of course, this was supposed to be a step towards a classless society, but fundamentally one could say Bakunin didn’t think so much power should be given to the state. It’d be prone to get hung up there, and who needs a state, anyway?

Bakunin further saw more revolutionary potential in the lumpenproletariat who Marx and Engels tended to dismiss. Briefly, if the proletariat is the working class, think about the unemployed.

Now, what does this have to do with the character on Lost? It’s not entirely clear, but the fact that the reference is so straightforward had me thinking about it from Mikhail’s first appearance, and I think this deepened my appreciation of his character.

Replace the dynamics with Marxists for those with Ben (and Jacob) and we might see this Bakunin as someone who believes the Others should operate differently. He’s committed to the cause but quibbles over the tactics. So perhaps he goes along, but with some reluctance.

Overall, though, Lost‘s Bakunin is such a heel that the name reference to the historical Bakunin almost feels like slander. Or perhaps he is intended to be something like a mirror/opposite of the Mikhail Bakunin in real life, as he prefers solitude and is quick to murder whereas his namesake seemed to believe that human beings could effectively live together without the guidance of some overarching institution of authority.

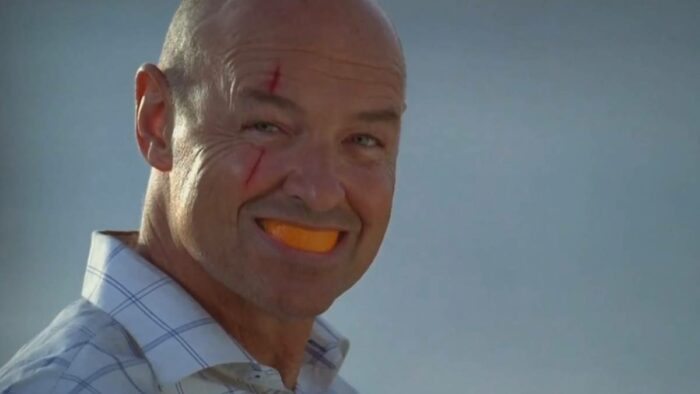

John Locke

John Locke was a preeminent thinker of the 17th century, in a time when what we would call science wasn’t really yet distinguished from philosophy, and who made significant contributions to political theory as well as epistemology. He presented a version of Social Contract theory, but is perhaps best known for this theory of property and the thought that this initial derives from mixing one’s labor with nature. I cut down some trees and build a cabin and that makes it my cabin, to put it oversimply.

And of course we can feel resonances between that and the John Locke who is a character on Lost. But it is in Locke’s theory of knowledge that I find the name reference to be most compelling. Locke was a proponent of Empiricism, asserting that knowledge derives from (sense) experience. This is in contrast to a thinker like Rene Descartes, who seemed to think that one could gain substantive metaphysical knowledge simply by reasoning correctly over the course of six days in a room alone.

In Lost, Locke may be the exemplar of the “man of faith” but I also see in him the spirit of his namesake. Bear in mind that back in the 17th century, empirical inquiry involved doing things like drinking mercury to see what would happen. Isaac Newton purportedly stuck a sewing needle into his eye socket and pushed it around, taking notes about what happened to his vision at the same time.

And there is a sense in which the John Locke of Lost is an empiricist—he is fundamentally open to the experiences of the Island rather than pushing them away on the basis of established “knowledge.” He meets a man who tells him he has to push a button to save the world, and so he does. Does he know that the world will end if he stops pushing it? No, but he also doesn’t know that it won’t. The crisis comes in the face of only being able to know the catastrophe will occur if you let it happen.

Jeremy Bentham

I don’t know if it’s unfar to choose Terry O’Quinn twice, but he’s great and the use of the name Jeremy Bentham in Lost definitely deserves its own entry.

Bentham is generally taken to be the founder of modern Utilitarianism, the theory which claims that morality consists in what produces the greatest overall happiness. One could certainly see Locke’s actions as Bentham along these lines, if we presume that returning to the Island would produce the greatest happiness as the end of the day, but I don’t really tend to think that Locke’s moral views would be best expressed in utilitarian terms, insofar as the theory insists that it is only consequences that are relevant to a moral calculus, whereas John Locke (the character in Lost) strikes me as rather a man of principle.

The thing about Jeremy Bentham and the use of his name in Lost that has always tickled me pink is rather that Bentham designated that upon his death his body was to be preserved as an auto-icon, and it has been kept on display for the past couple hundred years. Legend has it that Bentham’s corpse has, since his death, continued to attend meetings of the college council, marked as present but not voting unless there was a tie, in which case he always votes “Yea.”

That’s not true, but the auto-icon very much exists. You can go see it! Of course, the head didn’t quite keep properly, so it’s been replaced by a wax head, and I can’t claim to know the details of how the corpse has been maintained, but I did happen to know about all of this when I saw Lost for the first time, and continue to think it makes it absolutely hilarious that the writers chose to name Locke’s corpse Jeremy Bentham and have him continue to function as a character post mortem.

Jacob

I’m not entirely sure if Jacob in Lost is named after the character in the Bible or if Jacob is the biblical character. I kind of tend to think the latter, actually, but I suppose that’s a story for another day.

The reference is clear, regardless. Jacob, the younger twin to his brother Esau, nonetheless stole the latter’s birthright through coercion and deception. Don’t worry, though, we’re assured this was divine providence and Esau’s bad attitude is just sour grapes.

But so the two fought perpetually throughout their lives, with Esau being more of a nomadic hunter and Jacob more pastoral in nature. The apparent lesson being that Jacob deserved God’s blessing even though by right it should have gone to his older brother.

All of this seems to map on to the narrative that unfolds in Lost in a seamless way. Perhaps some details differ, but I take the biblical allusion in Jacob’s name to be rather obvious. Which of course leads me to think of the Man in Black as Esau, and to view him with a good degree of sympathy.

Maybe that has more to do with me, though, than with the biblical narrative, since Jacob is definitely the good guy there as well. But through this resonance I feel Lost manages to raise a deep question about the idea of a man like Jacob, and at the end of the day it seems important that he is surpassed and there is a new man in charge.

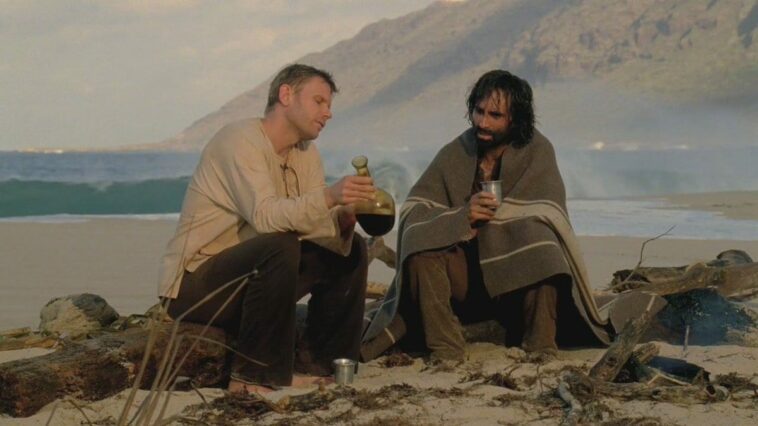

Desmond David Hume

David Hume, like John Locke, is widely regarded as a paragon of Empiricism, which is fair, but I find his reflections on personal identity to be most striking with regard to our friend Desmond, along with this passage from the conclusion of Book 1 of his Treatise of Human Nature:

Methinks I am like a man, who having struck on many shoals, and having narrowly escap’d shipwreck in passing a small frith, has yet the temerity to put out to sea in the same leaky weather-beaten vessel, and even carries his ambition so far as to think of compassing the globe under these disadvantageous circumstances. My memory of past errors and perplexities, makes me diffident for the future. […] And the impossibility of amending or correcting these faculties, reduces me almost to despair, and makes me resolve to perish on the barren rock, on which I am at present, rather than venture myself upon that boundless ocean, which runs out into immensity. This sudden view of my danger strikes me with melancholy, and as ’tis usual for that passion, above all others, to indulge itself, I cannot forbear feeding my despair, with all those desponding reflections, which the present subject furnishes me with in such abundance.

David Hume suggested that we have to live without certainty, and reframed knowledge as a matter of probability, which might put us in mind of the way that Desmond Hume pushes a button every 108 minutes even though he doesn’t know whether it does anything. Does he doubt that it’s necessary to save the world? Every single day.

Hume extended his skepticism even to his own personal identity over the course of time, noting that when he looked within he didn’t find some stable self or soul but always only the present moment in his mental life. Thus he’s not worried in the passage above about just going awry, but about losing his sense of self, because it has no firm basis. Like David Hume, Desmond David Hume perserveres even as he is driven almost to despair, and risks losing himself in the flow of time.

Ultimately, though, Hume suggests that it is our sociality that saves us from such a possibility (if we’re lucky at least). His friends come by to play some backgammon and drink some wine, and he is OK. The parallel to Desmond needing his constant in Penny as he is set adrift in time is, I think, clear, and his general affability mirrors the way that, by all acounts, everyone liked David Hume—even those who profoundly disagreed with his philosophical views.

So those are my favorite name references in Lost. What would be yours? Who are you mad at me for leaving off the list? Let me know in the comments!

Articles like this are what keep me coming back to 25YL (daily) and continuing my Patron subscription; it’s refreshing not to be fused to rehashing plot points but instead to be exposed to a unique thoughtfulness which expands and challenges perception, if not shifting paradigm. Bonus points for providing direct links to outside source material for further pondering, greatly appreciated!

Thanks so much!