Coming in the wake of the revelation of Laura’s killer to the audience in Episode 14 and the reinforcement of the image of Leland Palmer (Ray Wise)’s possession by BOB in Episode 15, Episode 16 is nothing if not pivotal in the story arc of Twin Peaks. In Episode 16, Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) exposes Leland as the murderer of Laura Palmer, Maddy Ferguson, and Teresa Banks. Yet the sense of finality and closure that might attend to the apprehension of a murder suspect is occluded by the recognition that BOB—the demonic spirit that possessed Leland in his childhood—could be the true killer. And so, in typical Lynchian fashion, the narrative resolution that would be is not. Beyond the significance of the diegetic unveiling of Laura’s killer, Episode 16 exemplifies the nexus between dreams, quantum theory, and magic that underpins the mythology of the entire series.

Leading up to the production of Episode 16, David Lynch, Mark Frost, and collaborators received what producer Tony Krantz has referred to as the “clarion call [from] ABC as to who killed Laura Palmer.” [1] In other words, by the time Episode 16 had rolled around, the creators of Twin Peaks were experiencing mounting studio pressure to bring about a resolution to the horribly enchanting mystery that enshrouded Laura Palmer’s murder and that propelled the show itself.

In her book Television Rewired, Martha P. Nochimson criticizes the industrial standard of television “story product” which made ABC uncomfortable with the lingering mystery of Twin Peaks. [2] She argues that Lynch revitalized television as a narrative medium by rejecting the formulaic qualities of perfect heroes and perfect narratives—for that matter, we might add perfect villains. In all, ABC’s insistence that Twin Peaks wrap up loose narrative ends and reveal the killer gave Episode 16 the quality of what some consider a “rushed […], careless handling of what ought to have been a major moment,” but this insistence on bringing about narrative simplicity also brought the heart of Twin Peaks’ thematic elements to the fore.

It was clear ABC didn’t know what to do with it. They knew they had something on their hands, but they weren’t really comfortable with it. There was always that tension of, will they keep it going?–-Tim Hunter

Episode 16 director Tim Hunter recalls in a 2018 interview that as Season 2 progressed, ABC’s lack of commitment to Twin Peaks cast a pallor on the entire production. The storyline devolved after the mystery of Laura’s death was resolved, David Lynch and Mark Frost became less involved with Twin Peaks as they moved on to feature-film projects, and by the end of Season 2, many of the cast and crew were affected by a general spirit of “cynicism and disillusionment.” In another interview with the hosts of “Twin Peaks Unwrapped,” Ben Durant and Bryan Kozaczka, Hunter ruefully expressed that he was not able to capture BOB’s presence as naturally as Lynch did and that his depictions of BOB inhabiting Leland’s body were somewhat forced by comparison. [3]

Regardless of any misgivings about the overall quality of Episode 16 as a result of a hastened narrative climax, studio pressures, and a lack of executive support, this episode is hands-down one of my personal favorites, and that might be because it is one that transparently imbues the show with elements of supernatural horror. Sure, BOB’s more subtle appearances in other episodes are chilling and afford him qualities of insidious power, but Hunter’s depictions of BOB inhabiting Leland are inescapably stark. Hunter has since directed episodes of prominent television shows that hinge on drama overlapping with horror—shows like Deadwood, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Dexter, and American Horror Story. In addition to Episode 16, Hunter directed Episode 4 and the penultimate episode of the second season, meaning that he influenced the initial portrayals of Lodge spirits’ connection with MIKE (the One-Armed Man) and Laura and Cooper’s shared dream.

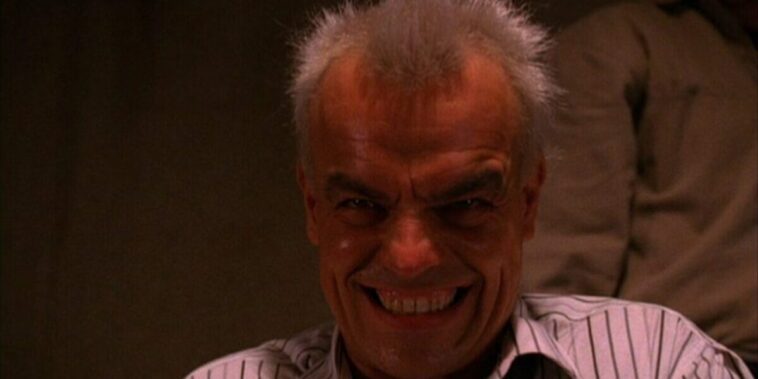

Despite Hunter’s uncertainty about his own depictions of BOB in comparison to Lynch’s, Ray Wise remembers that Hunter was very helpful in guiding him to depict BOB’s spirit in the final episode that Wise starred in. [4] To recount them, the two scenes in which we see BOB manifest through Leland in this episode include when Donna (Lara Flynn Boyle) stops by the Palmers’ to tell them about Laura’s secret diary and, of course, when BOB confesses to the murders after Leland is taken into custody. In between these open manifestations of BOB through Leland, it is interesting to note that BOB seems to be seething just beneath the surface of Leland’s personality. It is almost as though BOB is exuding the insane urgency of a caged animal throughout the episode, even before Leland is incarcerated.

More so than in previous episodes in the series, Leland exudes BOB’s frenetic energy even when he is interacting with other adults like Sheriff Truman and Agent Cooper. Many have speculated as to what prompts Leland/BOB to attack Donna when she brings him news about Laura’s secret diary. The moment that BOB emerges in Leland’s eyes in this scene is when Leland notices that Donna is wearing Laura’s sunglasses. Clearly, BOB is provoked by Donna and Maddy’s resemblances to Laura, but even more than that, he responds with frustrated rage when he is unable to control Laura’s effects and likenesses. In any case, BOB is transparently becoming stronger (or less careful), while Leland becomes increasingly unstable. [5]

I never had BOB in my mind. It was always Leland and when that old switch went off and he became something else, it was him. And whether it was another part of his brain kicking in or whatever you want to call it, I did not ever think about BOB. —-Ray Wise

It is difficult to speculate about BOB’s motivations and triggers because these thoughts always boil down to the ultimate question—is BOB real, or is he a figment of Leland’s imagination? Is he a parasitic spirit using Leland’s body as a vehicle to commit atrocities, or is he just the evil that men do? Wise attests that Leland is innocent, and he seems to identify strongly with Leland’s character since he uses first-person pronouns when referring to Leland. [6, 7] Mark Frost thinks differently. His view is that Leland is the murderer: “Ultimately, the human person has to take responsibility.” [8]

We can all talk until we’re blue in the face about whether or not Leland is culpable because that question brings us to fundamental ethical questions about truth, will, and personhood. I do know, however, that in the world of Twin Peaks and in Episode 16, the Black Lodge and Lodge spirits like BOB, MIKE, the Giant, and the Arm verifiably exist. In Episode 16, both the revelation that Laura and Cooper shared their dream in the Red Room at different times and the Giant returning Cooper’s ring prove that these spiritual entities exist and can influence the physical world in Twin Peaks. To quote Major Briggs adapting a quote from Hamlet, “Gentlemen, there is more on heaven and earth than is dreamt of in our philosophy.”

Early in the episode, Donna discovers that something was amiss with her earlier Meals on Wheels visit to Ms. Tremond. She learns from Andy that the sentence the young boy Pierre uttered later became the phrase that Harold left in his suicide note. Immediately, we are aware that Twin Peaks’ spookier elements are coming out to play in this episode. Donna brings Cooper to Mrs. Tremond’s, only to discover that the original Mrs. Tremond doesn’t exist and that Harold left Donna the missing pages of Laura’s secret diary. In those pages, Laura describes having the same dream that Cooper had in Episode 3 two nights before she died.

Even if it was only a dream, I hope he heard me. No one in the real world would believe me. —-Laura Palmer

In their shared dream, Laura and Cooper are in the Red Room of the Black Lodge, except Cooper is much older. Laura whispers the secret of her killer’s identity into Cooper’s ear; when Cooper experiences this dream in Episode 3, he wakes up with the knowledge of Laura Palmer’s killer but then forgets it. In Episode 16, MIKE reminds Cooper that the answer to the mystery of who murdered Laura Palmer is inside of him: he simply needs to unlock it. After Donna reads the contents of the last pages in Laura’s secret diary, Cooper reveals that the dream Laura described just before she died was the same dream that he had. Andy and Cooper both acknowledge that this is impossible, and yet it still happened.

It is easy to overlook the significance of this shared dream beyond its narrative utility in helping Cooper identify Laura’s murderer: the dream affirms the reality of shared consciousness that is accessed through the unconscious, which is the essence of Cooper’s and Lynch’s preoccupation with dream states. When we talk about communication in shared dreams that take place in disparate points of physical time and space, we begin to consider topics like quantum consciousness and the quantum unconscious. This confirmation of Cooper’s dreams as valid investigative tools (and as a means of interdimensional travel later in the series) propels the show’s underlying themes all the way through the end of The Return.

This connection between dreams, quantum reality, and identity is explored in the abstract at the culmination of The Return. Once Cooper’s consciousness is restored from the vacancy of his Dougie Jones tulpa persona, he returns to the Sheriff’s station in Twin Peaks in Part 17 and is present for BOB’s ultimate destruction. At this point, Cooper seems to instigate a split into two separate parallel realities, as depicted by his doubled face being overlaid onto himself in the station and his floating face uttering the phrase, “We live inside a dream.”

One version of Cooper travels to an alternate or parallel reality in the past and actually prevents Laura Palmer’s death in both realities. Part 18 depicts Cooper attempting and failing to restore the original reality before Laura’s death in this alternate reality, where Laura is not quite Laura, Cooper is not quite Cooper, and nothing (not just the owls, and certainly not the year) is what it seems. Cooper’s ability to undertake interdimensional time travel in the culmination of The Return, as well as his and Laura’s ability to communicate through dreams at disparate points in time and space, underpin Twin Peaks’ artistic speculations about the real implications of quantum field theory and its relationship to consciousness.

Back in Episode 16, once Cooper’s attention is directed again to his dream from Episode 3, he consults with MIKE about retrieving the information hidden in his dream and learns that he must now figure out how to ask the Giant to help him unlock the truth of Laura’s dream. To this end, Cooper devises what I would like to call the Ritual at the Roadhouse. He gathers everyone who has been considered a suspect or otherwise closely involved in the investigation—in all, Benjamin Horne, Leland Palmer, Harry Truman, Ed Hurley, Leo Johnson, Hawk Hill, Bobby Briggs, and Albert Rosenfield are present in the Roadhouse scene. They are later joined by Major Briggs, escorting the old waiter.

I call this scene a ritual because it contains many superficial elements of a solemn occult ceremony: we have a geometric placement of all the attendants, a prescribed order of events (particularly with the later arrival of Briggs and the Waiter), and, most importantly, an incantation. A final major element that contributes to the ritualistic quality of this scene is the intense lightning, which alludes to the ongoing theme of electricity as a means of transportation for spirits in Twin Peaks.

After the room is cleared of tables and chairs with a large space in the center, Cooper offers what I consider to be in this context an invocation to a ceremony. He addresses the men gathered around the room and explains that he believes that Laura’s killer is in the room; he describes the different (conventional and unorthodox) methods he has used to identify the murderer, then famously claims, “But now I find myself in need of something new, which, for lack of a better word, we shall call magic,” with thunder and lightning punctuating his sentence in response.

To say that we can qualify Cooper’s statement as an invocation is to say that he is calling upon a deity or spirit for assistance and, of course, that’s exactly what he’s doing: asking the Giant to unlock the secret embedded in his unconscious, in his and Laura’s shared dream. This statement also represents a definitive turning point for Cooper in that he is now openly embracing occult or supernatural methods to seek out the truth. [9] It is also important to note that Cooper dictates the conditions of this ritualistic scene based on his intuition. After the invocation, Truman asks, “Now what?” and Cooper responds, “Harry, I’m not entirely sure…Someone is missing.” Cue Major Briggs arriving with the Waiter precisely as the clock chimes 3:00. During this ritual, Cooper doesn’t consciously know what the prescribed set of circumstances required to achieve his will is, but he knows that it exists. He intuitively searches his unconscious mind for what is needed as the situation arises.

At this point, we already know that the old waiter is associated with the Giant, and later in the series when Cooper enters the Black Lodge, we learn that the two are “one and the same.” So in this scene, Cooper (as well as the audience) may not have consciously realized it yet, but he has summoned the Giant and the Giant has arrived, gum and all. It is the Waiter/Giant who utters the ritualistic incantation that drives Cooper into an altered state of consciousness for the duration of a flash of lightning. When Leland intimates to the Waiter in an odd, childlike voice that the gum he has was his favorite gum as a kid, the Waiter simply says, “That gum you liked is going to come back in style.” This was, of course, the statement that the Arm spoke backward in the Red Room in Cooper’s dream. Cooper then seems to relive this moment in the dream as he remembers. Laura is there, and she leans forward and whispers the secret into his ear: My father killed me. Then in the Roadhouse, the Giant appears before Cooper and returns the gold ring that he took when Cooper was shot.

At this revelation, Cooper casually pops the gum into his mouth as if this is something he has known all along. With Truman’s help, he proceeds to apprehend Leland surreptitiously under the guise of arresting Horne and by shoving Leland into the cell at the last second once they get to the station. I’ve always found this detail noteworthy. What stops Cooper from having Leland arrested outright at the Roadhouse? How does he know that Leland/BOB would thrash around like a wild animal once he knows he’s trapped? It seems that Cooper has already intuited that BOB is who he’s after—and that BOB is inhabiting Leland.

After confessing to the brutal murders in a chillingly callous manner and being left alone in his cell, BOB offers an incantation of his own before bludgeoning Leland to death by ramming his head repeatedly into the steel cell door. Immediately, Truman is questioning the reality of BOB, and in direct response, BOB chants Mike’s monologue with an additional verse: I’ll catch you with my death bag / You may think I’ve gone insane / But I promise / I will kill again. This brings us back to that ultimate question: Is BOB real, or is Leland just crazy? Or is BOB real, but Leland is equally culpable for being the person or “vehicle” committing these acts? Remember, Laura doesn’t whisper to Cooper that BOB killed her. She says her father killed her.

Either way, I believe that BOB is real—and don’t lie to me, I know you think he’s real, too. But if we accept that BOB is real, do we also accept that something like this could happen in our own world and not just in a place like Twin Peaks? Whether or not we believe something like this is feasible, the concept alone is horrifying. Both Kyle MacLachlan and Michael Horse (Hawk Hill) have stated that filming this scene was remarkably uncomfortable. Horse in particular has recalled that he didn’t want to be in the room during the filming of this scene because watching BOB come out of Leland was like “calling on evil” in real life. [10]

I didn’t want to be in that room when they were calling on that evil. It had become that real to me.–-Michael Horse

In all, Episode 16 is pivotal in the Twin Peaks narrative, and the themes that are prevalent in this episode are themes that underpin the entire series. This episode gives us valuable insight into the connections between dreams, spells, and quantum reality as they are represented in Twin Peaks. Even with all of this going on, this episode’s subplots and side narratives have important developments. Some of my favorite moments in this episode are when Lucy offers her “50/50 proposition” to Dick and Andy, and, of course, when Catherine delights in revealing her identity to Horne when she visits him in his own jail cell disguised as “Mr. Tojamura.”

What about you? What are some of your favorite parts of Episode 16? Do you agree with my take on its significance? Most importantly, do you think that BOB is real, or that he is just the evil that men do? Let us know in the comments below!

References

- Ben Durant and Bryon Kozaczka, Twin Peaks Unwrapped (Columbus, OH: Scott Ryan Productions, 2020), p93-96

- Martha Nochimson, Television Rewired: The rise of the auteur series (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2019), p32

- Durant and Kozaczka

- Brad Dukes, Reflections, An Oral History of Twin Peaks (Nashville, TN: Short/Tall Press, 2014), p213-216

- John Thorne, The Essential Wrapped in Plastic: Pathways to Twin Peaks (Dallas, TX: John Thorne, 2016), p138-143

- Durant and Kozaczka

- Dukes

- Thorne

- Thorne

- Dukes

- Dukes

I think it’s possible that BOB is an inhabiting spirit of negative energy that can slowly corrupt a person and eat away at who they are from the inside. BOB has the potential to bring out the darkest parts of someone’s soul, leading them to give way to awful negative impulses that would never be entertained or acted upon without BOB’s slow corruption of the person. BOB is the “evil that men do” because he has the power to bring out the worst in us, but ultimately it’s the person that BOB inhabits that succumbs to BOB and carries out the horrors in which BOB derives nourishment.

It’s one of my favorite episodes too. The one thing that’s always stuck with me is that Leland is told to “go into the light,” a common admonition to leave this world behind and go on to what we hope is a better one. But then in the last scene, some small animal is scurrying about, apparently trying to find shelter, when suddenly an owl swoops out of bright light and presumably kills it. So perhaps going into the light is not a safe journey. To me, a very powerful few minutes.